These sources relate to changes in the nature of the Cold War in the period 1960–1969.

SOURCE A

An extract from a speech by Nikita Khrushchev to the Supreme Soviet, 14 January 1960.

There exist two camps in the world today, each with a different social system. The countries in these camps form their policies on entirely different lines. In these circumstances the problem of peaceful coexistence – that is, of safeguarding the world against the disaster of a military conflict between these two essentially hostile systems, between the groups of countries in which the two systems dominate – is of supreme importance. It is necessary to see to it that the inevitable struggle between them becomes solely a struggle of ideologies and of peaceful competition [...]. Each side will demonstrate its advantages to the best of its ability, but war as a means of settling this dispute must be rejected. This then is coexistence as we Communists see it.

SOURCE B

Cartoon by Vicky (a British cartoonist), published in November 1962. The people in the cartoon are Kennedy, Khrushchev and Mao. The word “Chicken!” is used in some countries to suggest someone is withdrawing from or failing in some activity through fear or lack of nerve.

|

| “CHICKEN!” CALLS MAO FROM SAFETY |

SOURCE C

Extracts from the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Joint resolution by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, August 1964.

Section 2. The United States regards as vital to its national interest and to world peace the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia. Consonant [consistent] with the Constitution of the United States and the Charter of the United Nations and in accordance with its obligations under the Southeast Asian collective defence treaty, the United States is, therefore, prepared, as the President determines, to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member of the Southeast Asian defence treaty requesting assistance in defence of its freedom.

Section 3. This resolution shall expire when the President shall determine that the peace and security of the area is reasonably assured by international conditions created by action of the United Nations or otherwise, except that it may be terminated earlier by joint resolution of the Congress. Approved 10 August 1964.

SOURCE D

An extract from a speech by Marshal Lin to the 9th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing, 1 April 1969.

Since Brezhnev came to power, the Soviet revisionist clique has intensified its suppression of the Soviet people and increased the restoration of capitalism. Externally it has stepped up its collusion with US imperialism and its suppression of the revolutionary struggles of the people of various countries, intensified its exploitation of the various east European countries, and increased its threat of aggression against China. Its decision to send hundreds of thousands of troops to occupy Czechoslovakia and its armed provocation against China on our territory are two unacceptable acts carried out recently by Soviet revisionism. In order to justify its aggression the Soviet revisionists declare their theory of “limited sovereignty”. What does this rubbish mean? It means that your sovereignty is limited while his is unlimited. You won’t obey him? He will exercise his “international dictatorship” over you.

SOURCE E

An extract from Diplomacy by Henry Kissinger, New York, 1994. Kissinger was President Nixon’s Security Adviser from 1969 to 1973.

The age of America’s nearly total dominance of the world stage was drawing to a close. America’s nuclear superiority was eroding [diminishing], and its economic supremacy was being challenged by the dynamic growth of Europe and Japan, both of which had been restored by American resources and sheltered by American security guarantees. Vietnam finally signalled that it was high time to reassess America’s role in the developing world, and to find some sustainable ground between abdication [giving up control] and over-extension.

New opportunities for American diplomacy were presenting themselves as serious cracks opened up in what had been viewed throughout the Cold War as the communist monolith. Khrushchev’s revelations in 1956 of the brutalities of Stalin’s rule and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, had weakened the ideological appeal of communism for the rest of the world. Even more important, the split between China and the Soviet Union undermined Moscow’s pretence to be the leader of a united communist movement. All of these developments suggested that there was scope for a new diplomatic flexibility.

1. (a) Why according to Source A does Khrushchev think peaceful coexistence is important?

(b) What message is suggested by Source B?

2. Compare and contrast the state of Sino-Soviet relations as portrayed in Sources B, D and E.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations for historians studying the Cold War in the 1960s, of Sources A and C.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain why there was scope for new diplomatic flexibility in the Cold War in 1969.

November 2003

The following sources relate to United States involvement in the Vietnam War in the 1960s.

SOURCE A

Extract from The Cold War by Richard A. Schwartz, North Carolina 1997.

The Vietnam War must be viewed within its Cold War context. It began in the early 1960s as a classical American Cold War effort to halt Communist expansion in the underdeveloped regions by supporting a local regime to oppose the Communists. By the time it ended in 1973, however, it transformed both the Cold War and the United States itself by forcing Americans to examine the assumptions behind the war and the far reaching consequences it carried.

SOURCE B

Extract from the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, 10 August 1964, Joint Resolution of US Congress.

Naval units of the Communist regime in Vietnam, in violation of the principles of the Charter of the United Nations and of international law, have deliberately and repeatedly attacked United States naval vessels lawfully present in international waters; and have thereby created a serious threat to international peace; these attacks are part of a deliberate and systematic campaign of aggression that the Communist regime in North Vietnam has been waging against its neighbours and the nations joined with them in the collective defence of their freedom; the United States is assisting the peoples of South East Asia to protect their freedom and has no territorial, military or political ambitions in that area, but desires only that these peoples should be left in peace to work out their own destinies in their own way: therefore, be it resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that the Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.

SOURCE C

Extract from Peace Without Conquest, a speech by Lyndon B. Johnson at Johns Hopkins University, 7 April 1965.

Americans and Asians are dying for a world where each people may choose its own path to change. [...] It is the principle for which our sons fight tonight in the jungles of Vietnam.

The world as it is in Asia is not a serene or peaceful place. [...] North Vietnam has attacked the independent nation of South Vietnam. Its object is total conquest. [...] The nature of this conflict cannot mask the fact that it is the new face of an old enemy.

Over this war – and all Asia – is the deepening shadow of Communist China. China is a nation which is helping the forces of violence in almost every continent. The contest in Vietnam is part of a wider pattern of aggressive purposes.

Why are we in South Vietnam? [...] because we have a promise to keep. Since 1954 every American President has offered support to the people of South Vietnam. [...] over many years, we have made a national pledge to help South Vietnam defend its independence.

We are also there to strengthen world order. To leave Vietnam to its fate would shake the confidence of all people in the value of an American commitment. The result would be increased unrest and instability, even wide war. We are also there because there are great stakes in the balance. Let no one think for a minute that retreat from Vietnam would bring an end to the conflict. The battle would be renewed in one country and then another. The central lesson of our time is that the appetite of aggression is never satisfied.

SOURCE D

Editorial cartoon by Herblock in the Washington Post, 17 June 1965. [The tall man on the escalator is President Johnson, the other person represents the public.]

Source E

Extract from In Retrospect: The Lessons and Tragedy of Vietnam by Robert McNamara, New York 1995.

If we are to learn from our experience in Vietnam, we must first pinpoint our failures. [...]

We misjudged then – as we have since – the geopolitical intentions of our adversaries (in this case, North Vietnam and the Vietcong, supported by China and the Soviet Union), and we exaggerated the dangers to the United States of their actions.

We underestimated the power of nationalism to motivate a people (in this case, the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong) to fight and die for their beliefs and values – and we continue to do so today in many parts of the world.

We failed to draw Congress and the American people into a full and frank discussion and debate of the advantages and disadvantages of a large-scale US military involvement in South East Asia before we initiated the action.

1. (a) What reasons are given in Source B for supporting President Johnson’s actions as Commander in Chief?

(b) What message is portrayed by Source D?

2. In what ways are the views expressed in Source A supported by Sources C and E?

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Sources C and D for historians studying US involvement in the Vietnam War.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain to what extent you agree that “Vietnam was Johnson’s war”.

May 2004

These sources relate to developments in the Cold War in the early 1960s.

SOURCE A

Extract from O Strane I Mire by A Sakharov, New York, 1976, recalling a 1961 meeting at which Khrushchev spoke to leading Soviet nuclear scientists.

We were told that we had to prepare for a new series of nuclear tests, which were to provide support for the USSR's policy on the German question (the Berlin Wall). I wrote a note to Khrushchev, saying: "The revival of these tests will be a breach of the test-ban treaty and check the move towards disarmament: it will lead to a fresh round in the arms race, especially in the sphere of inter-continental missiles and anti-missile defence." I had this note passed to Khrushchev. He put it in his pocket. At dinner, he replied to the note in a speech. This, more or less, is what he said: "Sakharov is a good scientist, but he should leave foreign policy to those of us who are specialists. Strength alone can throw our enemy into confusion. We cannot say out loud that we base our policy on strength, but that is how it has to be."

SOURCE B

Extract from a Resolution [formal statement of intention] of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) Council of Ministers, 12 August 1961.

To stop hostile activities by revanchist [revengeful] and militaristic forces in West Germany and West Berlin, a border control will be introduced at the borders to the GDR, as is common on the borders of sovereign states. Borders to West Berlin will be sufficiently guarded and effectively controlled in order to prevent subversive activities from the West. Citizens of GDR will require a special permit to cross these borders. Until West Berlin is transformed into a demilitarized, neutral free city, residents of the capital of the GDR will require a special certificate to cross the border into West Berlin. Peaceful citizens of West Berlin are permitted to visit the capital of the GDR (East Berlin) upon presentation of a West Berlin identity card.

SOURCE C

Contemporary photograph of Soviet and American tanks confronting each other at Checkpoint Charlie, 27 October 1961.

SOURCE D

Extract from a television and radio address by President Kennedy, 22 October 1962.

Within

the past week, unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a

series of offensive missile sites are now in preparation [in Cuba]. The

characteristics of these new missile sites indicate two distinct types

of installations. Several of them include medium range ballistic

missiles, capable of carrying a nuclear warhead for a distance of more

than 1000 miles. Each of these warheads, in short, is capable of

striking Washington DC or any other city in the southeastern part of the

United States. Additional sites not yet complete appear designed for

intermediate range ballistic missiles ñ capable of travelling more than

twice as far [Ö] To halt this offensive buildup, a strict quarantine

[isolation] of all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba

is being initiated.

SOURCE E

Extract from a message from Harold Macmillan, British Prime Minister, to President Kennedy, 22 October 1962.

My dear Friend

I

have this moment received the text of your proposed declaration tonight

[...] What I think we must now consider is Khrushchev's likely

reaction. He may demand the removal of all American bases in Europe. If

he reacts in the Caribbean his obvious method would be to alert his

ships and force you into the position of attacking them. Alternatively,

he may bring some pressure on the weaker parts of the free world defence

system. This may be in South-East Asia, in Iran, possibly in Turkey,

but more likely in Berlin. If he reacts outside the Caribbean ñ as I

fear he may - it will be tempting for him to answer one blockade with

another. If Khrushchev comes to a conference he will of course try to

trade his Cuba position against his ambitions in Berlin and elsewhere.

This we must avoid at all costs, as it will endanger the unity of the

alliance.

1(a) According to Source A, what reservations did Sakharov express about the new series of Soviet nuclear tests?

(b) Why according to Source B, was the German Democratic Republic (GDR) introducing new border control regulations?

2. In what ways do Sources C and D support Khrushchev’s views on foreign policy expressed in Source A?

3.

With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and

limitations of Sources B and E for historians studying developments in

the Cold War in the period 1960-62.

4.

Using these sources and your own knowledge, assess to what extent

Berlin was the main centre of conflict in the Cold War in the early

1960s.

November 2004

These sources relate to Nixon's foreign policy of d'etente.

SOURCE A

Extract from Richard Nixon, First Inaugural Address, 20 January, 1969.

The greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peacemaker [...] Let all nations know that during this administration our lines of communication will be open. We seek an open world - open to ideas, open to the exchange of goods and people n- a world in which no people, great or small, will live in angry isolation. We cannot expect to make everyone our friend, but we can try to make no one our enemy. Those who would be our adversaries, we invite to a peaceful competition - not in conquering territory or extending power, but in enriching the life of man. As we explore the reaches of space, let us go to the new worlds together - not as new worlds to be conquered, but as a new adventure to be shared. With those who are willing to join, let us cooperate to reduce the burden of arms, to strengthen the structure of peace, to lift up the poor and the hungry.

SOURCE B

Extract from Rise to Globalism: American Foreign Policy since 1938 by Stephen Ambrose and Douglas G Brinkley; Eighth Revised Edition, New York, 1997.

It all came down to the program Nixon called Vietnamization. Six months after taking office, he announced that his secret plan to end the war was in fact a plan to keep it going, but with lower American casualties. He proposed to withdraw American combat troops, unit by unit, while continuing to give air and naval support to ARVN [Army of South Vietnam] and rearming ARVN with the best military hardware America had to offer [...] Nixon had high hopes for his policy when he started out [...] Dr Henry Kissinger had convinced him that there was a path to peace with honour in Vietnam and it led through Moscow and Peking. If the two communist superpowers would only refrain from supplying arms to the North Vietnamese, Kissinger argued, Hanoi would have to agree to a compromise peace, a policy he called 'linkage'. The United States would withhold favors and agreements from the Russians until they cut off the arms flow to Hanoi [...] Linkage assumed that world politics revolved around the constant struggle for supremacy between the great powers [...] Kissinger regarded North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos as pawns to be moved around the board of the great powers. He insisted on viewing the war as a highly complex game in which the moves were made from Washington, Moscow and Peking.

SOURCE C

American Cartoon, 1972 by Nancy King and editors published in A Cartoon History of United States Foreign Policy, New York, 1991. The three nations are represented by Mao, Brezhnev and Nixon.

|

| Nixon" "I'm not sure of the rules, but it looks like an interesting game." |

SOURCE D

Extracts from the Joint Communique between the People's Republic of China and the United States of America issued in Shanghai, 28 February, 1972.

The two sides agreed that countries, regardless of their social systems, should conduct their relations on the principles of respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states, non-aggression against other states, non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. International disputes should be settled on this basis, without resorting to the use or threat of force.

Both sides are of the view that it would be against the interests of the peoples of the world for any major country to collude [secretly plot] with another against other countries, or for major countries to divide up the world into spheres of interest.

SOURCE E

Extract from 'The White House Years' by Henry Kissinger, Boston, 1979.

With the SALT announcement on 20 May, we seized the initiative. It was followed [...] by the announcement of the Moscow summit, and a nearly uninterrupted series of unexpected moves that captured the "peace issues" and kept our opponents off balance [...] Whatever oneís views about détente in the abstract, in the context of 1971 and 1972 the carefully considered measures of the Administration toward the Soviet Union were imperative to prevent a long rush toward abdication of responsibility in America and among our allies. Our willingness to discuss détente had lured Brezhnev into an initiative about mutual force reductions that saved our whole European defense structure [... It was a classical example of why such a policy was needed to maintain the essential elements of national security if we were to avoid the destruction of our national defense and Alliance solidarity in the era of Vietnam.

1 (a) According to Source A, what were Nixon's objectives for his foreign policy?

(b) What political message is portrayed in Source C?

2. In what ways are the views expressed in Source B supported by Sources C and D?

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source E for historians studying the period of détente.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain what considerations prompted the United States, China, and the Soviet Union, to improve their relations.

May 2005

These sources relate to developments in the eastern bloc in 1968, and their impact on the Cold War.

SOURCE A

Extracts from a letter from the French Communist Party to Brezhnev, 23 July 1968.

Dear Comrade Brezhnev

You ask us to approve the letter sent to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia – on behalf of the central committees of the communist workers’ parties of five Warsaw Pact countries – offering direct outside assistance.

To our immense regret, it is impossible for us to comply with this request. In effect this letter goes against a principle that ought to be fundamental in relations between communist parties, and it starts a process that could have the most dire consequences for the cause of socialism and the international communist movement...

We are fully aware that it is vital for the leadership of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia to wage an effective struggle against all forces seeking to exploit the situation in order to do away with socialism in the country. However, we differ on the method to be used to achieve this objective.

In our opinion, direct outside intervention of any sort must be excluded and the leadership of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia must be persuaded to take action on its own.

SOURCE B

An American cartoon, August 1968 (reproduced in The World This Century by Neil DeMarco, London, 1997), showing the Soviet leaders, Brezhnev and Kosygin, dragging the Czechoslovak leader, Dubcek, towards the water.

|

| SOMEONE IS TAKING DUBCEK SURFING |

SOURCE C

An extract from a speech by Brezhnev to Polish workers in Warsaw, November 1968.

The measures taken by the Soviet Union, jointly with other socialist countries, in defending the socialist gains of the Czechoslovak people, are of great significance in strengthening the socialist community, which is the main achievement of the international working class.

The weakening of any of the links in the world system of socialism directly affects all the socialist countries, which cannot look indifferently upon this.

The implementation of “self-determinism” – in other words, Czechoslovakia’s detachment from the socialist community – would have brought Czechoslovakia into conflict with its own interests and would have been detrimental [dangerous] to the other socialist states.

SOURCE D

An extract from a speech by Lin Biao (Lin Piao) to the Ninth Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing, 1 April 1969.

Since Brezhnev came to power, the Soviet revisionist clique [group] has stepped up its collusion [secret understanding] with US imperialism and its suppression of the revolutionary struggles of the peoples of various countries, intensified its control over and its exploitation of the various east European countries ... and intensified its threat of aggression against China. Its dispatch of hundreds of thousands of troops to occupy Czechoslovakia, and its armed provocations against China on our territory are two unacceptable acts staged recently by Soviet revisionism.

In order to justify its aggression, the Soviet revisionist clique loudly proclaims its so-called theory of “limited sovereignty” and theory of “socialist community”. What does all this stuff mean? It means that your sovereignty is “limited”, while his is unlimited. You won’t obey him? He will exercise his “international dictatorship” over you — dictatorship over the people of other countries, in order to form the “socialist community” ruled by the new Tsars.

SOURCE E

An extract from Russia, America and the Cold War, 1949-1991 by Martin McCauley, London, 1998.

The Czechoslovaks were edging towards social democracy but their new leader, Alexander Dubcek, did not appreciate that his support of greater democracy in Czechoslovakia was perceived as a threat to socialist orthodoxy in Moscow. Tension increased and Moscow enquired about the American view of the situation. President Johnson informed the Soviets that the US would not intervene in what he considered a dispute within the communist bloc. The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia was therefore free to go ahead in August 1968, fatally weakening the communist movement.

West European parties, led by the Italians, sided with the reforming communists in Czechoslovakia and condemned Russian intervention. For a brief time, Eurocommunism, the democratic face of communism, flourished in western Europe. The invasion ended hopes for greater autonomy for enterprises in the Soviet Union and the slow decline of the Soviet economy set in. The Chinese vented their anger on what they perceived to be social imperialism. The Brezhnev Doctrine was born which obliged socialist states to intervene in one another’s affairs if socialism was perceived to be in danger. Who decided when socialism was in danger? Russia, of course. This in turn led to the fateful decision to intervene in Afghanistan in 1979. In June 1969 a conference of communist and workers’ parties was convened but the Chinese, North Vietnamese and North Koreans declined to attend. There was no world communist movement any more.

1 (a) Why, according to Source A, did the French Communist Party disagree with "direct outside intervention" in Czechoslovakia?

(b) What message is conveyed by Source B?

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed about Soviet foreign policy in Sources A and D.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations for historians studying developments in the eastern bloc in 1968 and their impact on the Cold War, of Source C and Source E.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain to what extent you agree with the verdict that the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 was an important turning point in the Cold War.

November 2005

These sources relate to Soviet-Cuban relations between 1962 and 1968

.

SOURCE A

A cartoon by Jensen, published in the Sunday Telegraph, a British newspaper, 4 November 1962, three days after President Kennedy announced all Soviet missile bases in Cuba had been destroyed.

|

| The figures in the cartoon are Fidel Castro and Nikita Khrushchev. The broken rocket is labelled 'Washington'. The launched rocket is labelled 'Mars'. |

SOURCE B

Comments by Khrushchev, after his dismissal as First Secretary, on meetings with Castro after the Missile Crisis, in Khrushchev Remembers: The Glasnost Tapes, Boston. Full content made public in 1990.

I talked with him [Castro] later too, after he had already been to the [Soviet Union] twice and was in a different frame of mind. Our meeting was exceptionally warm and allowed for a good exchange of opinions. We discussed the past from hindsight and conducted an analysis of the events in a calm atmosphere. I saw that he still did not understand... He still believed that we had installed the missiles not so much in the interests of Cuba, but primarily in the military interests of the Soviet Union and the whole Soviet camp.

I told Castro, "There is another aspect to this business. You wanted to start a war with the United States. If the war had begun we would somehow have survived, but Cuba no doubt would have ceased to exist. It would have been crushed into powder. Yet you suggested a nuclear strike!..." At the time Castro was a very hot-tempered person. We understood that he failed to think through the obvious consequences of a proposal that placed the planet on the brink of extinction.

SOURCE C

Extract from Profiles in Power: Castro by Sebastian Balfour, London, 1990.

Castro's assertiveness towards Moscow derived from a new sense of confidence. While the Sino-Soviet dispute had weakened the socialist bloc, it also gave Cuba a certain influence over the Soviet Union, which was anxious to keep Cuba on its side. Castro was careful, however, to keep his distance from the Chinese, who were trying to exploit the differences between Havana and Moscow. The limited support given to North Vietnam by both the Chinese and the Soviet Union raised the possibility of a third alignment of socialist forces including Hanoi, the Vietcong, the Cubans, and North Korea. The resistance of the North Vietnamese under the onslaught of American bombs must have been a source of immense encouragement to the Cuban leaders. Moreover, Cuba enjoyed the sort of prestige among Third World nations and in many sections of public opinion in the West that Moscow could hardly ignore.

SOURCE D

Extract from Fidel Castro by Robert Quirk, New York, 1993.

Since the early 1960s Fidel Castro and the occupants of the Kremlin [Soviet leaders] had engaged in a continuing game of more or less polite blackmail. Though their strategic aims differed, each side had need of the other and recognized the limits beyond which it could not go. Havana was fully aware that the success of the Cuban economy depended ultimately on decisions made by Soviet leaders. The country's industry - its factories, its mechanized state farms, its power-and-light system ñ ran on oil shipped from the Black Sea. As the Cuban economy expanded, so did its fuel requirement. By 1966 they had begun to run short, and in 1967 the Cubans asked Moscow to increase their deliveries by eight percent... Moscow would agree to add only a token two percent. The intent was clear though unstated ñ Fidel Castro should begin to behave himself if he expected more economic aid. In his New Yearís address, he stressed the seriousness of the problem in 1968. He refused to concede or admit fault, and he put the blame for the energy crisis on the Soviet Union.

SOURCE E

Extract from a speech given by Fidel Castro to the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party, August 1968.

We are here tonight to analyse the situation in Czechoslovakia. Some of the things we are going to say will, in some cases, conflict with the emotions of many. What cannot be denied is that the sovereignty of the Czechoslovak state was violated. From a legal point of view this cannot be justified. Not the slightest trace of legality existed. This action constitutes a bitter and tragic situation for the people of Czechoslovakia. In our opinion, the decision to invade Czechoslovakia can only be explained from a political point of view. We acknowledge the bitter necessity that called for the sending of Warsaw Pact forces into Czechoslovakia. We do not condemn the socialist countries that made that decision. We had no doubt that the political situation in Czechoslovakia was deteriorating and that the regime was heading towards capitalism and into the arms of imperialism. This would have dealt a strong blow to the interests of the worldwide revolutionary movement.

1 (a) According to Source C, what gave Castro the confidence to stand up to the Soviets in the mid-1960s?

(b) What message is conveyed by Source A?

2. Compare and contrast the views of Soviet-Cuban relations expressed in Sources C and D.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations for historians studying Soviet-Cuban relations in the 1960s, of Source B and Source E.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain the changing nature of Soviet-Cuban relations between 1962 and 1968.

May 2006

These sources relate to US Cold War policies and the Vietnam War.

SOURCE A

Extract from In Retrospect: the tragedy and lessons of Vietnam by Robert McNamara, New York, 1995.

My thinking about Southeast Asia in 1961 differed little from that of many Americans who had served in World War II. Having spent three years helping turn back German and Japanese aggression only to witness the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe after the war, I accepted the idea advanced by George Kennan in 1947, that the West, led by the United States, must guard against Communist expansion through a policy of containment. I considered this a sensible basis for decisions about national security and the application of Western military force ... And I knew that Indochina was a necessary part of our containment policy – an important bulwark [defence] in the Cold War.

SOURCE B

Extract from a press conference given by President Eisenhower, 7 April 1954, as reported in the Eagleton Digital Archive of American Politics, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey (www.eagleton.rutgers.edu/e-gov/e-politicalarchive-Vietnam-prelude.htm).

Robert Richards, Copley Press: Mr. President, would you mind commenting on the strategic importance of Indochina for the free world?

The President: You have both the specific and the general. First, you have the specific value of a locality in its production of material that the world needs.

Then you have the possibility that many human beings pass under a dictatorship that is hostile to the free world.

Finally, you have broader considerations that might follow the “falling domino” principle. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.

With respect to materials, two of the items from this particular area that the world uses are tin and tungsten. They are very important.

With respect to more people passing under communist domination, Asia has already lost some 50 million people to Communist dictatorship. We can’t afford greater losses.

When we come to the possible sequence of events, the loss of Indochina, Burma, Thailand, Malaya and Indonesia, now you are talking about millions and millions of people ... So, the possible consequences of the loss are incalculable to the free world.

Cartoon by Les Gibbard, published in The Guardian, a British newspaper, 3 May 1972. A US citizen is asking President Nixon a question about the South Vietnamese soldier on the ground.

|

| “If this boy of yours is real, how come we gotta wind him up all the time?” |

SOURCE D

Extract from President Nixon’s broadcast to the nation, 23 January 1973, as reported in The Cold War: history at source by E G Raynor, London, 1992.

At 12.30 pm Paris time today, 23 January 1973, the agreement on ending the war and restoring the peace was signed.

The cease-fire will take effect at midnight, 27 January 1973. The United States and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam hope that this agreement will secure stable peace in Vietnam and contribute to the preservation of lasting peace in Indochina and South-east Asia ...

Throughout the years of negotiation we have insisted on peace with honour. In the settlement that has now been agreed, all the conditions that I laid down then have been met ...

This settlement also meets the goals and has the full support of President Thieu of the Republic of Vietnam ...

The United States will continue to recognize the Government of the Republic of Vietnam as the sole legitimate government of South Vietnam. We shall continue to aid South Vietnam within the terms of the agreement, and we shall support efforts by the people of South Vietnam to settle their problems peacefully amongst themselves.

SOURCE E

Extract from The Limits of Liberty: American History 1607-1992 by Maldwyn Jones, London, published in 1983, second edition 1995. The author is Professor of

American History, University of London.

In 1972 Nixon stepped up air attacks on North Vietnam to new and terrible levels. Whether, as he was later to claim, the effect was to speed up the long-running Paris peace negotiations is disputed. Certainly a cease- fire agreement was signed in January 1973. Though Nixon described it as ‘peace with honour’ it was in fact a thinly disguised American defeat. It provided for the withdrawal of all remaining forces from Vietnam but not for a corresponding withdrawal of North Vietnamese troops from areas south of the 17th parallel. Nor did it settle the political future of South Vietnam or even attempt to define the cease-fire line. This fragile settlement soon broke down. The feeble and corrupt Saigon government steadily lost authority once the Americans had withdrawn. Finally, in April 1975, it surrendered unconditionally to the Communists. The American effort to preserve the Indo-Chinese peninsula from Communism was long-drawn out and ended in total failure.

1 (a) Why, according to Source A, was McNamara a supporter of the policy of containment?

(b) What message is conveyed by Source C?

2. Compare and contrast the views about the cease-fire agreement as expressed in Sources D and E.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source B and Source E for historians studying US Cold War policies and the Vietnam War.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain to what extent you agree with the statement, “The American effort to preserve the Indo-Chinese peninsula from Communism was long-drawn out and ended in total failure”. (Source E).

November 2006

These sources relate to the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and its effects on the Cold War.

SOURCE A

An extract from Europe and the Cold War, 1945–91 by David Williamson, London, 2001.

The Soviet retreat from Cuba, the growing atmosphere of détente and the Sino-Soviet split all combined to weaken Soviet control over Eastern Europe and provide some opportunities for the satellite states to pursue their own policies ... The Soviet Government’s efforts to consolidate its control over Eastern Europe ... suffered a serious setback when in January 1968 Alexander Dubcek became the First Secretary of the Czech Communist Party ... He attempted to create a socialist system that would be based on the consent of the people. In April 1968 he revealed his program for democratic change and modernization of the economy, which marked the start of what was called the Prague Spring. In June he abolished censorship, which led to a flood of anti-Soviet propaganda being published in Czechoslovakia. These developments began to worry Brezhnev and the other leaders of the Warsaw Pact.

SOURCE B

Cartoon by Herblock (an American cartoonist), published in September 1968. During the night of August 20-21, Soviet troops, joined by Warsaw pact allies, occupied Czechoslovakia.

SOURCE C

An extract from a speech by Leonid Brezhnev given on 12 November 1968.

The measures taken by the Soviet Union, jointly with other socialist countries, in defending the socialist gains of the Czechoslovak people are of great significance for strengthening the socialist states ... The CPSU (Communist Party of the Soviet Union) has always asserted that every socialist country must determine its own development on the path of socialism, in accordance with national circumstances. But when there is a threat to the cause of socialism in that country – a threat to the security of the socialist states as a whole – this becomes the concern of all socialist countries ...

Clearly, such action as military aid to suppress a threat to the socialist order is an extraordinary, forced measure which can be provoked only by the direct activity of the enemies of socialism ... Czechoslovakia’s detachment from the socialist states, would have brought it into conflict with its own vital interests and would have been dangerous (or threatening) to the other socialist states ...

SOURCE D

An extract from The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy, by Matthew J Ouitmet, Chapel Hill, 2003

Moscow’s goals in Czechoslovakia led most observers on both sides of the Iron Curtain to regard the intervention as a decisive Soviet victory. In the arena of East-West confrontation, the negative consequences of the operation were short-lived. Relations with the west experienced some setbacks, particularly with regard to the recently concluded Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty. The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were also delayed; President Johnson refused to travel to Leningrad in September 1968 and his successor, President Nixon, hesitated to re-establish contacts in 1969. Ultimately, however, the need to involve Moscow in negotiations with North Vietnam overcame American indignation, and Washington soon proved willing to improve relations in the interest of détente ...

The invasion of Czechoslovakia created instant tensions with the East European nations that had not taken part in the operation. As for the nations remaining in the Soviet-led alliance, the invasion confirmed that autonomous political reforms would no longer be tolerated. In the broader international socialist movement, the invasion seriously damaged Moscow’s ability to build a united front against the Chinese ...

SOURCE E

An extract from a speech by Zhou Enlai (Chou En-lai) [Chinese premier] on 23 August 1968 at Rumania’s National Day Reception.

A few days ago, the Soviet revisionist leading clique [critical term used to describe those who were no longer considered to be traditional Marxists] and its followers dispatched massive armed forces to launch a surprise attack on Czechoslovakia and swiftly occupied it [as the Chinese communists did with Tibet], with the Czechoslovak revisionist leading clique openly calling on the people not to resist, thus committing enormous crimes against the Czechoslovak people. This is the most obvious and most typical example of fascist power politics played by the Soviet Union ... It marks the total bankruptcy of Soviet revisionism.

The Chinese Government and people strongly condemn the Soviet revisionist leading clique and its followers for their crime of aggression – the armed occupation of Czechoslovakia – and firmly support the Czechoslovak people in their heroic struggle of resistance to Soviet military occupation ...

1. (a) According to Source A, what changes did Dubcek begin to introduce in Czechoslovakia in 1968?

(b) What message is suggested by Source B about the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia?

2. compare and contrast the reasons for the invasion of Czechoslovakia as expressed in Sources A and c.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source D and Source E for historians studying the cold War in the late 1960s.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, analyse the impact on the cold War of developments in Czechoslovakia in 1968.

May 2007

These sources relate to nuclear disarmament and the SALT I agreements in the 1970s.

SOURCE A

Extract from The Cold War by Bradley Lightbody, London 1999.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 took the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war and convinced both superpowers of the need for arms limitations. The immediate disarmament successes were the Test Ban Treaty of 1963, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty of 1968. By 1969, however, the Soviet Union achieved nuclear parity with the United States and the certainty of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) and the emerging competition to develop anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs) and, most significant, the multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) – that is the ability to place several independent targeted warheads on a single launcher or delivery vehicle – encouraged both superpowers to pursue disarmament. Détente and disarmament became two sides of the same coin in the 1970s as both superpowers engaged in efforts to halt the arms race... Arms limitations was attractive to both superpowers not only to reduce the danger of war but to curb the high financial costs of weapons development. Defence costs in 1969 were running at 39.7 billion dollars for the United States, approximately 7 per cent of national income, against 42 billion dollars for the Soviet Union, which was 15 per cent of the Soviet Union national income.

SOURCE B

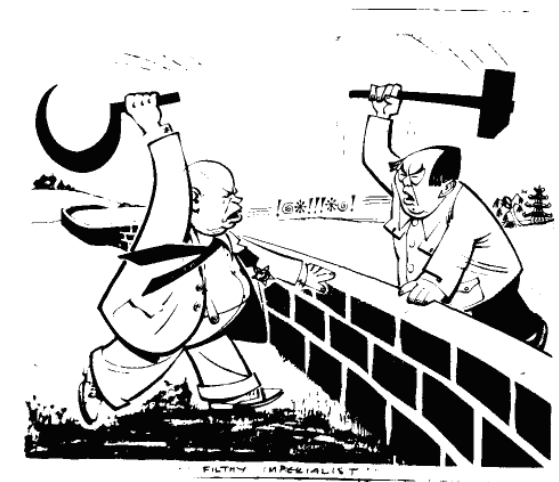

An American cartoon published in Time Magazine, November 1969 in the early stages of the SALT I talks. A 1969 Herblock cartoon, copyright by The Herb Block Foundation.

|

| “Shall We All Agree That There’s No Hurry?” |

... On 26 May 1972, at a summit in Moscow, President Nixon and Soviet leader Brezhnev signed the agreement that became known as SALT I. Both sides agreed to limit the number of anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs) and to freeze the number of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) at the level of those then under production or deployed. But SALT was silent on the issue of multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) so the Russian advantage in missile numbers was matched by the US advantage in deliverable warheads. The agreement did not cover medium-range and intermediate-range missiles, nor US bases in Europe. However, SALT was an important first step. It would eventually usher in a new era of détente between the superpowers. In 1972 the SALT I Treaty effectively froze the military balance between the Soviet Union and the US. They now realised that each side must be able to destroy each other, but only by guaranteeing its own suicide. In its mad way, this ensured a form of nuclear stability.

SOURCE D

An extract from Detente and Confrontation: American Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan by Raymond L Garthoff, Washington DC 1994. Garthoff is a former

American diplomat and was a member of the SALT I delegation.

The effort to achieve strategic arms limitation marked the first, and the most daring, attempt to follow a collaborative approach in meeting military security requirements. Early successes held great promises, but also showed the limits of readiness of both superpowers to take this path. SALT generated problems of its own and provided a focal point for objection by those who did not want to see either regulated military parity or political détente... The early successes of SALT I contributed to détente and were worthwhile. However, the widely held American view that SALT tried to do too much was a misjudgment: the real flaw was the failure of SALT to do enough. There was remarkable initial success on parity and on stability of the strategic arms relationship but there was insufficient political will (and perhaps political authority) to ban, or sharply limit, MIRVs. This failure led in the 1970s to the failure to maintain military parity between the USA and USSR.

SOURCE E

An extract from The Cold War 1945–1991 by Joseph Smith, Oxford 1998. Smith is a lecturer in American diplomatic history in the University of Exeter (UK).

... The domestic political difficulties of the Nixon administration contributed to the failure to conclude a new SALT treaty to replace the 1972 interim agreement, which was due to expire in 1977. The main obstacle to progress on arms control, however, was the evident unwillingness of both superpowers to abandon the arms race with each other. Behind the public advocacy of détente and disarmament, lay the reality that the freeze on missile numbers in SALT I had never been intended to prevent either side from continuing to develop and modernize its existing weapons... Both superpowers, however, wanted détente to continue and regarded the negotiating of a new arms control treaty as an essential element in the process...

1 (a) Why, according to Source A, were the superpowers convinced “of the need for arms limitations”?

(b) What message is conveyed by Source B?

2. In what ways do the views expressed about SALT I in Source c, support the conclusions expressed in source D?

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source D and Source E for historians studying disarmament attempts up to the end of the 1970s.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, evaluate the successes and failures of the nuclear disarmament process by the end of the 1970s.

November 2007

These sources relate to relations between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China in the 1960s.

SOURCE A

Extract from Khrushchev: The Man and His Era by William Taubman, professor of Political Science, New York 2000.

The Third Congress of the Romanian Communist Party was scheduled to open on June 20 (19 0) in Bucharest. Until June 18 it shaped up as routine. On that day, however, Khrushchev suddenly announced his decision to attend ... When he arrived, he then surprised all the delegates with an anti-Chinese attack. According to one account ... Khrushchev criticized Mao by name as ‘oblivious of any interests other than his theories, detached from the realities of the modern world.’... Peng [leader of the Chinese delegation] ... mocked Khrushchev for having no foreign policy except to blow hot and cold toward the West. Challenged, Khrushchev took his revenge; overnight he pulled all Soviet advisors out of China. According to the Chinese, Moscow withdrew 1390 experts, tore up 3 3 contracts, and scrapped 257 cooperative projects in science and technology...

SOURCE B

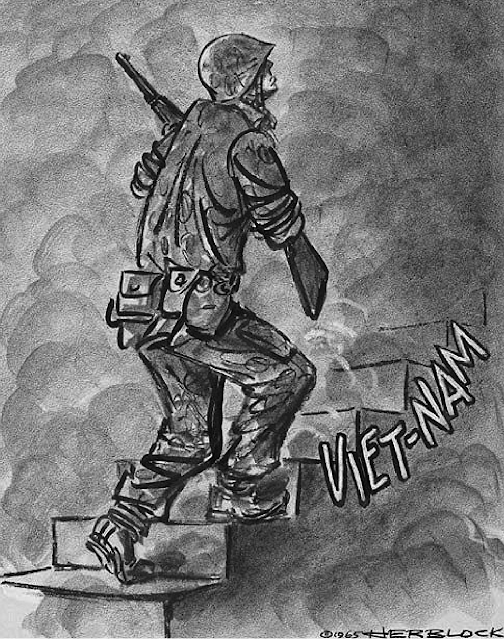

A political cartoon first published in the London Daily Mail on 23 September 1963.

|

| “Filthy Imperialist” |

SOURCE C

“A Retrospect of China-USSR and China-Russia Relations” by Rong Zhi from The Beijing Review, November 1999 (An internet information site of the current Chinese government).

In 19 64, Khrushchev announced the recall of all experts in China, thus disrupting the normal process of some large projects and bringing about much economic pressure. In 1964 , USSR leaders decided to increase troops along the Sino-Soviet border and station troops in the Mongolian People’s Republic, thereby exercising military pressure on China. Following the Zhenbao Island event in March, 19 69, the USSR deployed middle range nuclear missiles along the Sino-Soviet border and the Mongolian People’s Republic, enhancing the military threat to China. During the late 1950s and early 19 60s, Khrushchev totally changed the attitude toward China and deserted the policy of consulting with China and taking its views into consideration. Instead, he tried to control China. That is why the Sino-Soviet relationship changed from a friendly one to one of antagonism.

SOURCE D

Extract from Mao’s China and the Cold War by Chen Jian, professor of Chinese- American Relations, North Carolina, 2001.

On the one hand, Mao, especially after 19 2, repeatedly argued that in order to avert a Soviet-style ‘capitalist restoration’, it was necessary for the Chinese Party and people ‘never to forget class struggle,’ pushing the whole country toward another high wave of continuous revolution. On the other hand, Mao personally initiated the great debate between the Chinese and Soviet parties, claiming that the Soviet Party and state had fallen into the ‘revisionist’ abyss and that it had become the duty of the Chinese Party and the Chinese people to hold high the banner of true socialism and communism ... With the continuous radicalization of China’s political and social life (the Cultural Revolution in 19 ), the relationship between Beijing and Moscow rapidly worsened. By 19 3– ... the alliance ... had virtually died. On several occasions, Mao even mentioned that China now had to consider the Soviet Union, which represented an increasingly serious threat to China’s northern borders, as a potential enemy.

SOURCE E

Extract from Friends and Enemies: The United States, China, and the Soviet Union, 1948–1972 by Gordon H. Chang, an American historian, Stanford 1990.

The Cuban Missile Crisis in October 19 2 seemed to drive home to both Kennedy and Khrushchev the importance of arms control and of reducing tensions. Following the showdown the two leaders drew closer to each other, while Sino-Soviet relations continued to deteriorate. China accused Khrushchev both of recklessness in installing the missiles in the first place and of surrender in subsequently withdrawing them when confronted by the United States. Then, in November, Moscow adopted a neutral attitude toward China’s border fight with India, which was strongly backed by the United States. The Chinese took offence at Moscow’s lack of support...

In China the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, which broke out in May 19 , was an outgrowth of Mao’s effort to eliminate Soviet-style revisionism from the world Communist movement. In terms of Marxist-Leninist theory, “On Khrushchev’s Phoney Communism and its Historical Lessons for the World” was the most important of all the documents produced by the Sino-Soviet split. This remarkable essay, rumoured to be have been written by Mao himself, listed all the Soviet Union’s alleged failings, to construct a devastating critique ... [that] led inevitably to the conclusion that the Soviet Union was no longer a socialist country and that its anti-China hostility was the result of a new imperialism.

1 (a) According to Source A, why did Khrushchev’s actions cause tensions with the Chinese at the Third congress of the Romanian communist Party?

(b) What message is portrayed in Source B about relations between the USSR and china in the early 1960s?

2. compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources D and E about the reasons for Sino-Soviet disagreements.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations for historians studying relations between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of china in the 1960s, of Sources c and E.

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain why the Sino-Soviet relationship in the 1960s changed from a “friendly one to one of antagonism”, (Source c).

Prescribed Subject 3 the Cold War, 1960 to 1979

These sources relate to the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962.

Source A

Extract from The Cold War: A Very Short Introduction by Robert McMahon, New York, 2003

Over the past four decades, scholars, policy analysts, and former governmental officials have vigorously debated every aspect of this near-catastrophe, often varying sharply in their interpretive judgments. While some have praised Kennedy’s masterful crisis management and remarkable cool under fire, others have blasted [criticised] the American president for his willingness to risk nuclear war and the almost certain deaths of tens of millions of Americans, Soviets, Cubans, and Europeans, over the emplacement of missiles that did not fundamentally alter the prevailing nuclear balance. Former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, who sat in on the ExCom [Executive Committee of the National Security Council] meetings, later attributed JFK’s Cuban success to “plain dumb luck”. That may be the most apt coda [final chapter] for this whole affair, especially if one recognizes how close the world actually came to nuclear war in October 1962. On the other hand, one must acknowledge Kennedy’s instinctive caution and prudence [wisdom], in the face of pressure from his military advisers for a more aggressive response, was instrumental to the peaceful ending of an affair of unparalleled danger.

Source B

Comments by Theodore Sorensen, a member of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, as quoted in Dean Acheson; The Cold War Years, 1953–71 by Douglas Brinkley, New Haven, 1991

I remember Dean Acheson coming to our meeting and saying that he thought we should knock out Soviet missiles in Cuba by air strike. Someone asked him: “If we do that, what do you think the Soviet Union will do?” He said, “I think I know the Soviet Union well. I know what they are required to do in the light of their history and their posture around the world. I think they will knock out missiles in Turkey.” And then the question came again, “Well, then, what do we do?” “Well,” he said, “I believe under our NATO treaty, with which I was associated, we would be required to respond by knocking out a missile base inside the Soviet Union.” “Then what do they do?” “Well,” he said, “then that’s when we hope cooler heads will prevail and they’ll stop and talk.”

Source C

Extract from a telegram from Khrushchev to Kennedy, October 26, 1962. Taken from the website of the Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

URL: www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/diplomacy/forrel/cuba/cuba084

... Let us show statesmanlike wisdom. I propose: We, for our part, will declare that our ships, bound for Cuba, will not carry any kind of armaments. You would declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its forces and will not support any sort of forces which might intend to carry out an invasion of Cuba. Then the necessity for the presence of our military specialists in Cuba would disappear ... Mr President, we and you ought not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot of war, because the more the two of us pull, the tighter that knot will be tied. And a moment may come when that knot will be tied so tight that even he who tied it will not have the strength to untie it, and then it will be necessary to cut that knot, and what that would mean is not for me to explain to you, because you yourself understand perfectly of what terrible forces our countries dispose ... Consequently, if there is no intention to tighten that knot and thereby to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie that knot. We are ready for this.

Source D

Extract from a telegram from Kennedy to Khrushchev, October 27, 1962. Taken from the website of the Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

URL: www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/diplomacy/forrel/cuba/cuba095

I have read your letter of October 26th with great care and welcomed the statement of your desire to seek a prompt solution to the problem. The first thing that needs to be done, however, is for work to cease on offensive missile bases on Cuba and for all weapons systems in Cuba capable of offensive use to be rendered inoperable, under effective United Nations arrangements ...

As I read your letter, the key elements of your proposals – which seem generally acceptable as I understand them – are as follows:

1) You would agree to remove these weapons systems from Cuba under appropriate United Nations observation and supervision; and undertake, with suitable safeguards, to halt the further introduction of such weapons systems into Cuba

2) We, on our part, would agree ... (a) to remove promptly the quarantine measures now in effect and (b) to give assurances against an invasion of Cuba ...

If you will give your representative similar instructions ... the effect of such a settlement on easing world tensions would enable us to work toward a more general arrangement regarding “other armaments,” as proposed in your second letter which you made public. I would like to say again that the United States is very much interested in reducing tensions and halting the arms race ...

Source E

Drawing “This Hurts Me More Than It Hurts You”. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, drawing by Edmund S. Valtman, (reproduction number LC-USZ62-130423)

In this cartoon Valtman characterises Khruschev as a dentist and Castro as a patient.

9. (a) Why, according to Source A, was Kennedy successful in handling the Cuban Missile Crisis? [3 marks]

(b) What message is conveyed by Source E? [2 marks]

11. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source C for historians studying the Cuban Missile Crisis. [6 marks]

12. Using these sources and your own knowledge, explain why the Cuban Missile Crisis did not lead to open war between the United States and the Soviet Union. [8 marks]

Example from student written under test conditions (click to enlarge):

The same student during a visit to Munich's Amerikahaus when it held an exhibition on the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis beside Source E

November 2008

These sources relate to United States Cold War policies and the Vietnam War.

Source A

Extract from President Johnson’s Message to Congress, August 5 1964.

Last night I announced to the American people that the North Vietnamese regime had conducted further deliberate attacks against US naval vessels operating in international waters, and I had therefore directed air action against gunboats and supporting facilities used in these hostile operations. This air action has now been carried out with substantial damage to the boats and facilities. Two US aircraft were lost in the action. After consultation with the leaders of both parties in the Congress, I further announced a decision to ask the Congress for a resolution expressing the unity and determination of the United States in supporting freedom and in protecting peace in South East Asia.

These latest actions of the North Vietnamese regime has given a new and grave turn to the already serious situation in South East Asia. Our commitments in that area are well known to the Congress. They were first made in 1954 by President Eisenhower. They were further defined in the South East Asia Collective Defense Treaty approved by the Senate in February 1955. This treaty with its accompanying protocol obligates the United States and other members to act in accordance with their constitutional processes to meet communist aggression against any of the parties or protocol states.

Source B

Extract from “Joint Resolution of Congress, H J RES 1145”, August 7 1964. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled:

That the Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.

Section 2. The United States regards as vital to its national interest and to world peace the maintenance of international peace and security in South East Asia. In accordance with the Constitution of the United States, the Charter of the United Nations and its obligations under the South East Asia Collective Defense Treaty, the United States is, therefore, prepared, as the President determines, to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member or protocol state of the South East Asia Collective Defence Treaty requesting assistance in defence of its freedom.

Section 3. This resolution shall expire when the President shall determine that the peace and security of the area is reasonably assured by international conditions created by action of the United Nations or otherwise, except that it may be terminated earlier by resolution of the Congress.

Source C

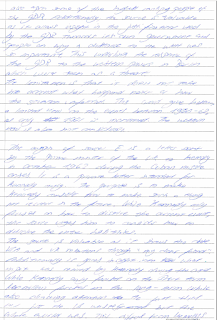

“The Other Ascent Into The Unknown” – A 1965 Herblock Cartoon, copyright by The Herb Block Foundation.

Source D

Extract from Senator Ernest Gruening’s statement during the Senate debates on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Congressional Record, August 6-7 1964.

Regrettably, I find myself in disagreement with the President’s South East Asian policy ... The serious events of the past few days, the attack by North Vietnamese vessels on American warships and our reprisal, strikes me as the inevitable and foreseeable concomitant [result] and consequence of US unilateral military aggressive policy in South East Asia ... We now are about to authorise the President, if he sees fit, to move our armed forces ... not only into South Vietnam, but also into North Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and of course the authorisation includes all the rest of the SEATO nations. That means sending our American boys into combat in a war in which we have no business, which is not our war, into which we have been misguidedly drawn, which is steadily being escalated. This resolution is a further authorisation for escalation unlimited. I am opposed to sacrificing a single American boy in this venture. We have lost far too many already ...

Source E

“McNamara asks Giap: What happened in the Tonkin Gulf?”, The Associated Press, November 9, 1995. Used with permission of The Associated Press

Copyright © 2008. All rights reserved.

When former Defence Secretary Robert McNamara met the enemy’s leading strategist on Thursday, he raised a question he’d saved for 30 years: “What really happened in the Tonkin Gulf on August 4, 1964?”

“Absolutely nothing,” replied retired General Vo Nguyen Giap.

Both sides agree that North Vietnam attacked a US Navy ship in the gulf on August 2 as it cruised close to shore. But it was an alleged second attack two days later that led to the first US bombing raid on the North and propelled America deep into war.

Many US historians have long believed the Johnson administration fabricated the second attack to win congressional support for widening the war. But for McNamara, Giap’s word was the clincher.

“It’s a pretty damned good source,” he said after the meeting.

9. (a) Why, according to Source A, did President Johnson believe it was necessary to ask for congressional action? [3 marks]

(b) What message is conveyed by Source C? [2 marks]

10. Compare and contrast the views expressed about United States military involvement in Vietnam in Sources A and D. [6 marks]

11. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source B and Source E for historians studying United States involvement in the Vietnam War. [6 marks]

12. Using these sources and your own knowledge examine the reasons for the United States escalating its military involvement in the Vietnam War in the mid 1960s. [8 marks]