Paper 1 Tips:

Paper 1 is formulaic – questions always follow the same

format. 1 hour (+5 mins reading time), 4 questions – DON’T RUN OUT OF TIME,

DON’T OVERTHINK THINGS

Question 1 – Source interpretation - Maximum 7 minutes!

a) “What, according to Source X…?” – Worth [3 marks] – just

pull out information from the source – no explanation, just fact

b) “What is the message conveyed by Source Y? [2 marks] –

pull out key points from your interpretations, back up with information from

the source.

Question 2 – Compare and Contrast Sources – Maximum 10

minutes!

Two structures:

“Compare and contrast the views expressed in X with those in

Y” – Don’t describe the view of the sources. Simple – 2 paragraphs, one

comparing (similarities) and one contrasting (differences) – ALWAYS BACK UP

WITH INFORMATION FROM THE SOURCES.

“To what extent do X and Y support the views expressed in

Z?” – briefly summarise the views expressed in Z and then do 1 paragraph

comparing and contrasting X with them, then another paragraph comparing and

contrasting Y with them. [6 marks]

Question 3 – Source Evaluation – Maximum 15 minutes

“With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the

value and limitations of Source A and Source B for historians studying…”

Do 1 paragraph about one source, then 1 paragraph about the

other – DO NOT COMPARE/CONTRAST.

Remember Origin and Purpose – must reference the two when

analysing the sources’ values and limitations – e.g. Because this source is a

speech by a government official… , Because the source aims to persuade, it may…

[6 marks]

Question 4 – Essay Question – 20 minutes

“Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse...”

Structure your answer as a mini essay – remember to

reference all of the sources, naming them – In source A…. Source B states that…

etc.

You must include a balance of your own knowledge about the

issue being discussed as well – this knowledge will come in the form of the

revision that you have done for Paper One using the following notes. Make sure

that you reach a conclusion and have an argument, and, for full marks, refer or

acknowledge the other side of the argument. [8 marks]

Paper 1 Specimen paper

These sources relate to the Locarno Conference, 1925.

SOURCE A Extract from a speech by Gustav Stresemann after the signing of the

Locarno Treaty,16 October 1925.

URL: http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/GERstresemann.htm

We have undertaken the responsibility of initialling the treaties

because we live in the belief that only by peaceful cooperation of states and

peoples can that development be secured, which is nowhere more important than

for that great civilized land of Europe whose peoples have suffered so bitterly

in the years that lie behind us. We have more especially undertaken it because

we are justified in the confidence that the political effects of the treaties

will prove to our particular advantage, in relieving the conditions of our political life. But great as is the

importance of the agreements that are signed here, the treaties of Locarno will

only achieve their profoundest importance in the development of the nations if

Locarno is not to be the end, but the beginning of confident cooperation among

the nations.

SOURCE B Extract from a speech by James Maxwell Garnett to the

Empire Club of Canada, 26 November 1925. Garnett was the Secretary of League of

Nations’ Union of Great Britain.

URL: http://www.empireclubfoundation.com/details.asp?SpeechID=282

But while the Locarno treaties have increased security along the

frontier they have added considerably to general security among the nations, I

want you to reflect what this means. Every nation in Europe can feel that not

only the British Foreign Secretary and the French Foreign Office, but the

German Foreign Minister too, will be present within a few hours to quench the

smouldering fires of war wherever they appear in the future. Then, after

disarmament and security and arbitration, the Locarno agreements are largely

concerned with the provision of means for a peaceful settlement of

international disputes between Germany and her enemy neighbours … We think that

Locarno, reinforced by Geneva, gives us good means for believing that we are

not now far from agreements between governments to get rid of war – that is to

say, nearly all agreements except the Soviet Republics, United States of

America, and Mexico and Turkey.

SOURCE C Extract from the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office website.

Extract from the “History of the FCO” page.

Locarno represented a defeat for those in France who had hoped for a

revived alliance with Great Britain. Along with Italy, Britain had guaranteed a

frontier rather than an ally, and henceforth was, in theory at least, committed

as much to Germany as to France and Belgium. The obligation to give immediate

military assistance in the event of a “flagrant” [serious] violation of the

treaty was also both ambiguous in its wording and likely to be impracticable in

its application. As had already been evident before 1914, the speed of modern

warfare had made joint contingency planning an essential prerequisite

[requirement] for the rendering of such aid. This was a point that Poincaré had

made during the discussions for an Anglo-French guarantee treaty in 1922. But

Locarno seemed to preclude [make impossible] any joint military talks between

Britain and France. After all, if the British military authorities engaged in planning

with their opposite numbers in France, the Germans might quite reasonably claim

that they had an equal right to be consulted. Yet for Britain to join in

bilateral [two-way] discussions with both powers with a view to assisting

either in the event of a Franco-German war would clearly be ludicrous

[ridiculous].

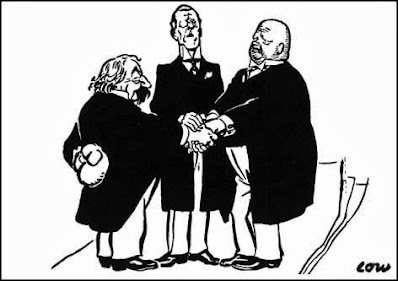

SOURCE D A cartoon by David Low depicting Aristide Briand,

Austen Chamberlain and Gustav Stresemann, taken from the London Evening

Standard, 8 September 1925.

France wanted to strengthen the League of Nations’ covenant by a

protocol engaging all members to the help of any member attacked. Taken from Europe Since Versailles, by David Low, London, 1940.

SOURCE E Extract from Germany 1866–1945,

by Gordon Craig, Oxford, 1978.

Stresemann’s initiative was therefore successful, but his difficulties

were just beginning. In the negotiations that resulted, in October 1925, in the

conclusion of the Treaty of Mutual Guarantee [Locarno], by which the states bordering

on the Rhine abjured [gave up] the use of force in their mutual relations and,

together with Britain and Italy, guaranteed the demilitarization of the

Rhineland and the existing western frontiers, and in the parallel negotiations

agreed upon on the terms for Germany’s admission to the League of Nations.

Stresemann’s view was that the Rhineland Pact and Germany’s willingness to

enter the League were positive contributions to European security and that

their logical consequence should be the evacuation of the whole of the

Rhineland before 1930, the date set by the treaty

These questions relate to the Locarno Conference, 1925.

1. (a) What, according to Source E, was the significance of

the Locarno Conference?

[3 marks]

(b) What message is conveyed by Source D?

[2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed about the

Locarno Conference in Sources B and C.

[6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, discuss the

value and limitations of Source A and Source C for historians studying the 1925

Locarno Conference.

[6 marks]

4. Using these sources and your own knowledge, analyse

the importance of the Locarno Conference for international relations between 1925 and 1936.

[8 marks]

In-class student example under test conditions (click to enlarge)

May 2010

These sources and questions relate to the Abyssinian Crisis (1935–36).

SOURCE A

Extract from the Covenant of the League of Nations, 1919.

Article 16 – Should any member of the League resort to war in disregard of its covenants under Articles 12, 13 or 15, it shall be deemed to have committed an act of war against all other members of the League, which hereby undertake immediately to subject it to the severance [cutting off] of all trade or financial relations, the prohibition of all exchange between their nationals and the nationals of the covenant-breaking state, and the prevention of all financial, commercial or personal business between the nationals of the covenant-breaking state and the nationals of any other state, whether a member of the League or not.

It shall be the duty of the Council in such cases to recommend to the several governments concerned what effective military, naval or air force the members of the League shall contribute to the armed forces to be used to protect the covenants of the League.

SOURCE B

Statement about a meeting between British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, and a delegation of the League of Nations on 13 December 1935, marked “strictly confidential”.

[The prime minister] assured us that he held faithfully to all his pledges with regard to the League and suggested that the interview should be both frank and confidential. The prime minister said that the League’s policy is still the policy of the [British] government and we were all in agreement in desiring that the policy should be effective. Translating desire into action, however, raised extremely difficult questions. He then explained the great gravity of the European situation, including the danger that Mussolini might make a “mad dog” [irrational] attack on the British fleet. Though the results of such an attack must in the long run be the defeat of Italy, the war might last some time and produce both losses and diplomatic complications of a serious kind. Meantime we were bound to consider whether we could rely on effective support from any other member of the League. No member except Great Britain had made any preparations for meeting an attack. As to France, the whole French nation had a horror of war.

SOURCE A

Extract from the Covenant of the League of Nations, 1919.

Article 16 – Should any member of the League resort to war in disregard of its covenants under Articles 12, 13 or 15, it shall be deemed to have committed an act of war against all other members of the League, which hereby undertake immediately to subject it to the severance [cutting off] of all trade or financial relations, the prohibition of all exchange between their nationals and the nationals of the covenant-breaking state, and the prevention of all financial, commercial or personal business between the nationals of the covenant-breaking state and the nationals of any other state, whether a member of the League or not.

It shall be the duty of the Council in such cases to recommend to the several governments concerned what effective military, naval or air force the members of the League shall contribute to the armed forces to be used to protect the covenants of the League.

SOURCE B

Statement about a meeting between British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, and a delegation of the League of Nations on 13 December 1935, marked “strictly confidential”.

[The prime minister] assured us that he held faithfully to all his pledges with regard to the League and suggested that the interview should be both frank and confidential. The prime minister said that the League’s policy is still the policy of the [British] government and we were all in agreement in desiring that the policy should be effective. Translating desire into action, however, raised extremely difficult questions. He then explained the great gravity of the European situation, including the danger that Mussolini might make a “mad dog” [irrational] attack on the British fleet. Though the results of such an attack must in the long run be the defeat of Italy, the war might last some time and produce both losses and diplomatic complications of a serious kind. Meantime we were bound to consider whether we could rely on effective support from any other member of the League. No member except Great Britain had made any preparations for meeting an attack. As to France, the whole French nation had a horror of war.

“The Road from Rome”, cartoon appearing in The New York Times depicting

Mussolini during the Abyssinian Crisis, 6 October 1935.

“The Road from Rome”

SOURCE D

Extract from Africa in War and Peace by Eric S Packham, 2004. The author,

who was in Africa at the time of the Abyssinian Crisis, served in the British Army in

the Gold Coast (Ghana) during the Second World War.

We all felt it was an ignominious [humiliating] ending to the high hopes which had been placed on

the League of Nations when the Assembly refused to take the one decisive measure which would have

halted the invasion – the prohibition of the exports of oil to Italy, without which Mussolini could not have

supplied his invading forces ... In 1935 Laval’s main foreign policy aim was to maintain an alliance with

Italy, so it was more important to have Mussolini as an ally against Hitler than to defend Haile Selassie

against him. Also Hoare and Laval apparently believed that Mussolini might go to war against Britain

if Britain should impose an oil sanction against Italy or cut Italy’s communications with Abyssinia ...

In 1935 Britain was the leading power in Europe and should have accepted responsibility for taking the

lead and dealing effectively with the Abyssinian situation. The other League members were not backward

in imposing sanctions against Italy, but unfortunately Britain failed to give an effective lead until it was

too late.

SOURCE E Extract from a speech by Haile Selassie to the League of Nations, June 1936.

I, Haile Selassie Emperor of Abyssinia am here today to claim that justice which is due to my people and the assistance promised to it eight months ago when fifty nations asserted that aggression had been committed in violation of international treaties ... What real assistance was given to Ethiopia by the fifty-two nations who had declared the Rome Government guilty of a breach of the Covenant and had undertaken to prevent the triumph of the aggressor? ... I noted with grief, but without surprise that three powers considered their undertakings under the Covenant as absolutely of no value. ... What, then, in practice, is the meaning of Article 16 of the Covenant and of collective security? ... It is collective security: it is the very existence of the League of Nations. It is the value of promises made to small states that their integrity and independence be respected and ensured ... it is the principle of the equality of states. ... In a word, it is international morality that is at stake.

-

(a) What, according to Source A, was the significance of Article 16 of the Covenant of

the League of Nations?

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source C?

-

Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources B and D about British policy during

the Abyssinian Crisis.

-

With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source D

and Source E for historians studying the Abyssinian Crisis.

- Using the sources and your own knowledge, assess the reasons why the League of Nations’ policy of collective security was difficult to apply in the Abyssinian Crisis.

In-class student example under test conditions (click to enlarge)

November 2010

These sources and questions relate to the retreat from the Anglo–American Guarantee.

SOURCE A

Extract from the Fontainebleau memorandum of 25 March 1919, written by David Lloyd George, British Prime Minister. Taken from Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, Ray Stannard Baker, New York, 1922.

Finally, I believe that until the authority and effectiveness of the League of Nations has been demonstrated, the British Empire and the United States ought to give France a guarantee against the possibility of a new German aggression. France has special reason for asking for such a decree. She has twice been attacked and twice invaded by Germany in half a century. She has been attacked because she has been the principal guardian of liberal and democratic civilization against Central European autocracy on the continent of Europe. It is right that the other great Western democracies should enter into an undertaking which will ensure that they stand by her side in time to protect her against invasion, should Germany ever threaten her again or until the League of Nations has proved its capacity to preserve the peace and liberty of the world.

SOURCE C

An extract from a series of talks between Édouard Herriot (French Prime Minister) and Ramsey Macdonald (British Prime Minister) 21–22 June 1924. Taken from The Lost Peace, Anthony Adamthwaite, London, 1980.

Monsieur Herriot:

I understand the situation in which Mr MacDonald finds himself, but since we are speaking as good friends, I must explain to him the situation of France ... My country has a dagger pointed at its breast, within an inch of its heart. Common efforts, sacrifices, deaths in the war, all that will have been useless if Germany can once more have recourse to [opportunity for] violence. France cannot count only on an international conference, and the United States are a long way off ... I speak to you here from the bottom of my heart, and I assure you that I cannot give up the security of France, who could not face a new war.

Mr MacDonald:

I shall do all in my power to avoid a new war, for I am certain that in that case it would not be only France but all European civilization that would be crushed ... I do not wish to take an easy way to join in an offer to France of a military guarantee of security. I should only be deceiving you.

SOURCE D

An extract from Europe in the Twentieth Century, Robert Paxton, New York, 1975. Paxton is a Professor of History at Columbia University.

On the western front, the United States and Britain had left France the sole guarantor of its own security. The failure of the United States Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles also meant the lapse of the simultaneous treaties that provided for automatic United States and British aid in case of German attack. French leaders felt betrayed, for they had moderated [reduced] their demands on Germany at the Peace Conference in return for this promise of future outside support. Although the French government tried to negotiate a substitute treaty of mutual defence with Britain alone during 1921 and 1922, the negotiators were unable to agree on how automatic British support of the French along the Rhine should be, for British public opinion was increasingly fearful of being drawn into another war by French aggression. As for European frontiers further east, no British government would make any commitments at all until 1939.

SOURCE E

An extract from The League of Nations, F S Northedge, UK, 1986. Professor Northedge was a Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics.

France had forgone one vital element in her security system at the Peace Conference in 1919, namely the separation of the west bank of the Rhine from Germany, in exchange for guarantees against unprovoked aggression by Germany offered by the British and American leaders, Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson. But this had fallen into disuse with the non-ratification of the treaties by the United States, and, with the resulting failure of that country to join the League, France considered the Covenant too weak to defend her against German aggression. When negotiations for an Anglo–French defence pact failed at the Cannes Conference in January 1922, French opposition to any disarmament scheme without a foolproof security system was confirmed.

1. (a) What does Source A suggest about Lloyd George’s attitude towards French security?

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and D about French security.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A

and Source E for historians studying the Anglo–American Guarantee.

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the consequences of the failure of the Anglo–American Guarantee on international relations between 1920 and 1926.

May 2011

These sources and questions relate to the enforcements of the provisions of the treaties, disarmament and the London Naval Conference (1930).

SOURCE A

Statement by US president H.Hoover at a press conference about the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, 22 July 1930. Taken from “The American Presidency Project” (online).

I shall have the gratification [pleasure] of signing the naval treaty this afternoon at 3 o’clock. With the ratification by the other governments the treaty will translate an emotion deep in the hearts of millions of men and women into a practical fact of government and international relations. It will renew again the faith of the world in the moral forces of goodwill and patient negotiation as against the blind forces of suspicion and competitive armament. It will mark a further long step toward lifting the burden of militarism from the backs of mankind and to speed the march forward of world peace. It will lay the foundations upon which further constructive reduction in world arms may be accomplished in the future. We should, by this act of willingness to join with others in limiting armament, have dismissed from the mind of the world any notion that the United States entertains ideas of aggression, imperial power, or exploitation of foreign nations.

SOURCE B

Extract from British and American Naval Power: Politics and Policy 1900–1936 by Phillips Payson O’Brien, 1998. The author is a lecturer in Modern History at the University of Glasgow, UK.

With the first London Naval Conference the naval arms race control process reached its apex [peak]. Parity [equality] between America and Britain was agreed to for every type of warship while Japan had accepted a smaller ratio for every category except submarines. The tragedy of the London Conference is that while it marked a considerable success in the arms control process, it was not a lasting achievement. Within six years naval arms control would be at an end. No ships were scrapped and naval construction increased markedly after the conference. It must also be kept in mind that the London Naval Treaty was a temporary agreement. The British were careful to tell the Americans that the London agreements extended only until 1935, after which the Royal Navy “would have to have more cruisers”. Also, when the French and the Italians chose not to sign the London agreements the British inserted a clause which would enable them to withdraw.

Source C

These sources and questions relate to the retreat from the Anglo–American Guarantee.

SOURCE A

Extract from the Fontainebleau memorandum of 25 March 1919, written by David Lloyd George, British Prime Minister. Taken from Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, Ray Stannard Baker, New York, 1922.

Finally, I believe that until the authority and effectiveness of the League of Nations has been demonstrated, the British Empire and the United States ought to give France a guarantee against the possibility of a new German aggression. France has special reason for asking for such a decree. She has twice been attacked and twice invaded by Germany in half a century. She has been attacked because she has been the principal guardian of liberal and democratic civilization against Central European autocracy on the continent of Europe. It is right that the other great Western democracies should enter into an undertaking which will ensure that they stand by her side in time to protect her against invasion, should Germany ever threaten her again or until the League of Nations has proved its capacity to preserve the peace and liberty of the world.

SOURCE C

An extract from a series of talks between Édouard Herriot (French Prime Minister) and Ramsey Macdonald (British Prime Minister) 21–22 June 1924. Taken from The Lost Peace, Anthony Adamthwaite, London, 1980.

Monsieur Herriot:

I understand the situation in which Mr MacDonald finds himself, but since we are speaking as good friends, I must explain to him the situation of France ... My country has a dagger pointed at its breast, within an inch of its heart. Common efforts, sacrifices, deaths in the war, all that will have been useless if Germany can once more have recourse to [opportunity for] violence. France cannot count only on an international conference, and the United States are a long way off ... I speak to you here from the bottom of my heart, and I assure you that I cannot give up the security of France, who could not face a new war.

Mr MacDonald:

I shall do all in my power to avoid a new war, for I am certain that in that case it would not be only France but all European civilization that would be crushed ... I do not wish to take an easy way to join in an offer to France of a military guarantee of security. I should only be deceiving you.

SOURCE D

An extract from Europe in the Twentieth Century, Robert Paxton, New York, 1975. Paxton is a Professor of History at Columbia University.

On the western front, the United States and Britain had left France the sole guarantor of its own security. The failure of the United States Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles also meant the lapse of the simultaneous treaties that provided for automatic United States and British aid in case of German attack. French leaders felt betrayed, for they had moderated [reduced] their demands on Germany at the Peace Conference in return for this promise of future outside support. Although the French government tried to negotiate a substitute treaty of mutual defence with Britain alone during 1921 and 1922, the negotiators were unable to agree on how automatic British support of the French along the Rhine should be, for British public opinion was increasingly fearful of being drawn into another war by French aggression. As for European frontiers further east, no British government would make any commitments at all until 1939.

SOURCE E

An extract from The League of Nations, F S Northedge, UK, 1986. Professor Northedge was a Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics.

France had forgone one vital element in her security system at the Peace Conference in 1919, namely the separation of the west bank of the Rhine from Germany, in exchange for guarantees against unprovoked aggression by Germany offered by the British and American leaders, Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson. But this had fallen into disuse with the non-ratification of the treaties by the United States, and, with the resulting failure of that country to join the League, France considered the Covenant too weak to defend her against German aggression. When negotiations for an Anglo–French defence pact failed at the Cannes Conference in January 1922, French opposition to any disarmament scheme without a foolproof security system was confirmed.

1. (a) What does Source A suggest about Lloyd George’s attitude towards French security?

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and D about French security.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A

and Source E for historians studying the Anglo–American Guarantee.

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the consequences of the failure of the Anglo–American Guarantee on international relations between 1920 and 1926.

May 2011

These sources and questions relate to the enforcements of the provisions of the treaties, disarmament and the London Naval Conference (1930).

SOURCE A

Statement by US president H.Hoover at a press conference about the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, 22 July 1930. Taken from “The American Presidency Project” (online).

I shall have the gratification [pleasure] of signing the naval treaty this afternoon at 3 o’clock. With the ratification by the other governments the treaty will translate an emotion deep in the hearts of millions of men and women into a practical fact of government and international relations. It will renew again the faith of the world in the moral forces of goodwill and patient negotiation as against the blind forces of suspicion and competitive armament. It will mark a further long step toward lifting the burden of militarism from the backs of mankind and to speed the march forward of world peace. It will lay the foundations upon which further constructive reduction in world arms may be accomplished in the future. We should, by this act of willingness to join with others in limiting armament, have dismissed from the mind of the world any notion that the United States entertains ideas of aggression, imperial power, or exploitation of foreign nations.

SOURCE B

Extract from British and American Naval Power: Politics and Policy 1900–1936 by Phillips Payson O’Brien, 1998. The author is a lecturer in Modern History at the University of Glasgow, UK.

With the first London Naval Conference the naval arms race control process reached its apex [peak]. Parity [equality] between America and Britain was agreed to for every type of warship while Japan had accepted a smaller ratio for every category except submarines. The tragedy of the London Conference is that while it marked a considerable success in the arms control process, it was not a lasting achievement. Within six years naval arms control would be at an end. No ships were scrapped and naval construction increased markedly after the conference. It must also be kept in mind that the London Naval Treaty was a temporary agreement. The British were careful to tell the Americans that the London agreements extended only until 1935, after which the Royal Navy “would have to have more cruisers”. Also, when the French and the Italians chose not to sign the London agreements the British inserted a clause which would enable them to withdraw.

Source C

SOURCE D

Extract from The Lights that Failed by Zara Steiner, 2005.

Neither the Italians nor the French signed the new limitation pact. France and Italy shared a common land border and were colonial rivals in North Africa. Relations, particularly since Mussolini had taken power, were uneasy, if not strained. For the Italians, lagging far behind the French, the navy became more than a status symbol; it would herald [signal] the building of the new empire. The French argued that if parity [equality] was conceded, the Italians could concentrate their fleet in the Mediterranean and achieve local naval superiority as the French fleet was dispersed through the Mediterranean, the English Channel, and North Atlantic.

The London Naval Treaty of 1930, with only three signatures to its key provisions, represented the high point of inter-war naval limitation; it could not be extended and could not be maintained. There were unique political reasons that had made the apparent compromise possible: American reluctance to translate financial power into naval might; the British decision to cut back on naval construction; and the continuing conservatism of the government in Tokyo.

SOURCE E

Extract from a speech by Winston Churchill to the British House of Commons, 2 June 1930.

This conference is the supreme failure of all conferences. We have seen what it does for our naval defence. But what of other countries? France and Italy – their relations have been definitely worsened. There was no particular assertion of naval competition but, by bringing this on to the table, you have compelled both these nations to assert a demand for absolute parity [equality] which will undoubtedly lead to large naval expenditure. There is tension created between America and Japan which did not exist three months ago. And what of Anglo–American friendship? It is important, as I believe it is the foundation of future safety. And after five years of this it will all have to be done over again. Once again the Great Powers will meet around the table, having focused their attention upon these details, and compare their naval power more. This time, in 1935, our navy will be definitely and finally weaker. I cannot think that it is a wise course of policy for us to pursue.

1. (a) What, according to Source B, was the significance of the 1930 London Naval Conference?

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source C?

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources D and E about the London Naval Conference.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source B for historians studying the 1930 London Naval Conference.

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, discuss the extent to which you agree with the view that the London Naval Conference was unsuccessful.

November 2011

These sources and questions relate to the Geneva Disarmament Conference (1932–1934).

SOURCE A Extract from The League of Nations by George Gill, 1996. George Gill was a professor of History at Fordham University, New York.

Mussolini was convinced that the key to political and economic stability was the “collaboration of the four great Western Powers” and therefore proposed a four power pact in which France, Germany, Great Britain and Italy would support treaty revision and pledge equality to Germany if the [Geneva] Disarmament Conference failed to do so. The French found the equality clause objectionable and removed it from the final draft of the pact, but the plan also antagonized the smaller nations attending the [Geneva] Disarmament Conference as another humiliating example of major power negotiations that ignored them. League officials realized that Mussolini’s insistence on leadership by the stronger nations threatened the constitutional principles under which the Assembly and Council functioned.

SOURCE B Extract from a memorandum by Brigadier Temperley to the British Cabinet, 16 May 1933. Brigadier Temperley was the military advisor to the British delegation at the Geneva Disarmament Conference.

If it is dangerous to go forward with this disarmament, what is then to be done? There appears to be one bold solution. France, the United States and Britain should address a stern warning to Germany that there can be no disarmament, no equality of status and no relaxation of the Treaty of Versailles unless a complete reversion of present military preparations and tendencies takes place in Germany. Admittedly this would provoke a crisis and the danger of war will be brought appreciably nearer. Britain would have to say that it insists upon the enforcement of the Treaty of Versailles, and in this insistence, with its hint of force in the background, presumably the United States would not join. But Germany knows that she cannot fight at present and we must call her bluff. She is powerless in the face of the French army and our fleet.

SOURCE C Extract from The Origins of the Second World War in Europe by P M H Bell, 1993. P M H Bell was a lecturer in History at the University of Liverpool, UK, specializing in European History.

In 1932 the British government agreed in principle to abandon the assumption that no major war was expected for ten years, but it also decided that while the Disarmament Conference was is session no action would be taken to rearm. It was politically impossible to begin rearmament during the conference. Instead, the British laboured tirelessly to find the basis for an agreement on arms limitation, which meant changing the positions of France and Germany, by bringing French armaments down and allowing German armaments to rise ... The British later proposed an increase in the German army from 100 000 to 200 000, while the French army would be reduced, and then agreed that Germany should have an air force half the size of the French. The French government too, under pressure from domestic opinion and reluctant to isolate itself from Britain, made considerable concessions during the conference. Public respectability was thus given to German rearmament, which was already secretly under way, as the British government knew.

SOURCE D Extract from the Report of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry (The Nye Report), US Congress, Senate, 74th Congress, 2nd session, 24 February 1936.

In 1932, another disarmament conference was held at Geneva. By this time the failure to prevent the rearmament of Germany had resulted in great profits to the French steel industry, which had received large orders for the building of the continuous line of fortifications across the north of France, to the French munitions companies, and profits were beginning to flow into the American and English pockets from German orders for aviation supplies. This in turn resulted in a French and English aviation race. With Germany openly rearming, the much-heralded disarmament conference, which convened in 1932, has failed completely. It was pointed out by a committee member that some representatives were aware that “the effect of the failure to check the [Versailles] Treaty violation even goes to the extent of making a subsequent disarmament convention, if not improbable in its success, at least calculated to produce only an unworkable document”.

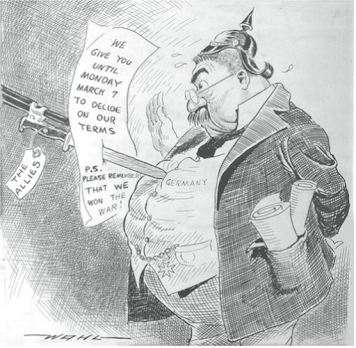

SOURCE E A cartoon by David Low, published 2 October 1933 in the London Evening

Standard

“WELL – WHAT ARE YOU GOING TO DO ABOUT IT NOW?”

- (a) Why, according to Source A, was there opposition to Mussolini’s plan for a four power pact? (b) What is the message conveyed by Source E?

- Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources B and C about the Geneva Disarmament Conference (1932–1934).

- With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source B and Source D for historians studying the Geneva Disarmament Conference (1932–1934).

- Using the sources and your own knowledge, explain why the Geneva Disarmament Conference (1932–1934) failed to achieve its aims.

These sources and questions relate to the League of Nations: effects of the absence of major powers.

SOURCE A

Extract from a speech by President Woodrow Wilson in Omaha, Nebraska, USA, 8 September 1919.

For the first time in history the advisers of mankind are to be drawn together and concerted all over the world ... Germany is for the time being left out because we did not think that Germany was ready to come in. She says that she made a mistake. We now want her to prove it by not making the same mistake again ... When an individual has committed a criminal act, the punishment is hard, but the punishment is not unjust ... Every great fighting nation in the world is on the list of those who are to constitute the League of Nations. I say every great nation, because America is going to be included among them, and the only choice my fellow citizens is whether we will go in now or come in later with Germany; whether we will go in as founders of this covenant of freedom or go in as those who are admitted after they have made a mistake and regretted it.

SOURCE B

Cartoon published in the Wichita Beacon, Kansas USA, 1919, depicting Woodrow Wilson talking to Uncle Sam whilst a man representing the United States Senate looks into the mouth of a donkey. "Looking a gift horse in the mouth" refers to the notion that one should not criticise someone trying to help.

SOURCE C

Extract from Reconstituting the League of Nations, by Julia E. Johnsen, published by the H. W. Wilson Company, New York, 1943.

The League was not allowed to become the great agency hoped for by President Wilson to correct the undesirable conditions that inevitably crept into the Versailles Treaty and other post-war treaties ... Nearly every assessment of the League of Nations made in the past twenty years points out that the first and principal difficulty was the failure to achieve a universal or near-universal membership. This fateful decision of the United States, which deprived the League from the beginning of a very great moral and material influence, was accompanied by an equally fatal decision in Paris in 1919 which kept Germany and the Soviet Union out of League membership until 1926 and 1934 respectively. The psychological effects of these decisions doubtless went very far in poisoning the atmosphere in which the infant League was intended to grow and prosper.

Membership alone, of course, was not enough. To be effective it had to be coupled with wholehearted cooperation. But failure to agree on major political questions, like disarmament and security, together with the League’s condemnation of specific acts of aggression, led to the successive withdrawal of Germany, Japan and Italy from the League. Later still, the Soviet Union was expelled for her aggression on Finland.

SOURCE D

Extract from a speech given by German journalist Wolfgang Schwarz at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, London, 11 February 1931.

Germany applied at Versailles to be admitted as a member of the League, and as you all know, membership was refused. It was said that the time had not yet come to admit Germany into the community of nations. The movement for the League and the new world founded on the League was killed in Germany by the attitude of the Powers. After such a refusal Germany felt that the League was only a second War Council or Ambassador’s Conference, that it was nothing but an instrument to maintain the peace treaties. Rightly or wrongly she felt that all the decisions were made to keep her down and to prolong war policy into peace.

SOURCE E

Extract from Patrick O. Cohrs (2008) The Unfinished Peace after World War I: America, Britain and the Stabilisation of Europe 1919–32, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

It has been claimed that if America had joined the League the German problem could have been solved even without stabilizing Germany as a Republic – by automatically involving Washington in the “European balance of power” and thus containing the German ambitions. In all likelihood, as French anxieties at Versailles underlined, even with British and American support the League would have been too feeble and inflexible an institution to serve its central purpose: to ensure security for a Europe devastated by war. It would have required an extensive test period – to prove that its principal powers were willing to enforce its covenant – before gaining legitimacy. The League’s key members had to pave the way for Germany’s admission and ensure the institution’s workability thereafter. As it came into being, the League could not be the post-war’s key instrument of security.

1. (a) What, according to Source C, were the problems affecting the League of Nations? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source B? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and E about the effects of the absence of major powers in the League of Nations. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source D for historians studying the problems of initial membership of the League of Nations. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the impact of the absence of major powers on the League of Nations. [8 marks]

November 2012

These sources and questions relate to the principle of collective security and early attempts at peacekeeping (1920–1925).

SOURCE A

Extract from a speech made by President Woodrow Wilson, 25 September 1919, in Colorado, USA, promoting the League of Nations.

They [member states] enter into a solemn promise to one another that they will never use their power against one another for aggression; that they will never threaten the territorial integrity of a neighbour; that they will never interfere with the political independence of a neighbour; that they will abide by the principle that great populations are entitled to determine their own destiny and that they will not interfere with that destiny; and that no matter what differences arise amongst them they will never resort to war without first having done one or other of two things – either submitted the matter of controversy to arbitration, in which case they agree to abide by the result without question, or submitted it to the consideration of the Council of the League of Nations.

SOURCE B

Extract from the minutes of the fourteenth meeting of the Council of the League of Nations, League of Nations Official Journal, 24 June 1921.

The Council at its meeting of 24 June 1921, having regard to the fact that the two parties interested in the fate of the Åland Islands have consented that the Council of the League of Nations should be called upon to effect a settlement of the difficulties which have arisen, and that they have agreed to abide by its decision.

Decides:

1. The sovereignty of the Åland Islands is recognized to belong to Finland.

[...]

4. The Council has requested that the guarantees will be more likely to achieve their purpose, if they are discussed and agreed to by the Representatives of Finland with those of Sweden, if necessary with the assistance of the Council of the League of Nations, and, in accordance with the Council’s desire, the two parties have decided to seek out an agreement. Should their efforts fail ... the Council of the League of Nations will see to the enforcement of these guarantees.

SOURCE C

Cartoon from British magazine Punch, 26 March 1919.

|

| President Woodrow Wilson: “Here’s your olive branch. Now get busy.” Dove of Peace: “Of course I want to please everybody, but isn’t this a bit thick?” |

SOURCE D

Extract from Fascist Ideology: Territory and Expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922–1945 by Aristotle A Kallis, 2000. Aristotle A Kallis is Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at Lancaster University, UK.

In August 1923, a car carrying a League of Nations’ arbitration team on the Greek–Albanian border was ambushed in northern Greece ... As the incident had happened inside Greece’s national territory, the Italian government held Athens responsible for the murder and issued a strong ultimatum, demanding a massive compensation ... After the occupation and bombardment of Corfu by the Italian air force the case was referred to international arbitration; not, however, to the League of Nations, but to the Conference of the Ambassadors. The reason for this decision was that the French and British governments preferred to resolve the crisis without resorting to collective security in accordance with the Covenant of the League ... The negotiations were long and difficult, disrupted by Mussolini’s refusal to reconsider the amount of financial compensation demanded from the Greek government ... In the end, a compromise formula was agreed which enabled the Fascist regime to get away with aggression and receive the full compensation it had initially demanded in return for the immediate withdrawal of the Italian forces from Corfu.

SOURCE E

[Extract from Aristotle A Kallis (2000). Fascist Ideology: Territory and Expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922–1945, Routledge: London and New York.]

Extract from the article “The League of Nations and the Settlement of Disputes” by Lorna Lloyd, 1995. Lloyd is a Professor of International Relations at the University of Keele, UK.

But Greece itself confused the issue by appealing initially to both the Conference of Ambassadors and the League and ... when the Italian representative questioned the right of the Council to deal with the dispute, Lord Cecil of Britain asked the interpreter to read aloud the articles of the Covenant about disputes between League members. In a tense and silent room this was a clever tactic. For without bringing any allegation against the Italian Government ... he showed the world the firm intention of the British Government to uphold the Covenant.

Although Mussolini publicly proclaimed the Corfu incident a victory and had the overwhelming majority of Italians behind him, he knew he had been defeated. He might not have minded earning the label of being an international bully, but he had intended to keep Corfu and all he received was his compensation ... The impact of the new League morality had made itself felt, and Mussolini had been unable to ignore the League. The other great powers did not turn their backs on their League obligations.

1. (a) What, according to Source B, was the decision of the Council of the League of Nations concerning the Åland Islands?

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source C?

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources D and E about the Corfu incident.

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source D for historians studying principles of collective security and early attempts at peacekeeping (1920–1925).

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, discuss the effectiveness of principles of collective security and early attempts at peacekeeping (1920–1925).

May 2013

These sources and questions relate to the Ruhr Crisis (1923).

SOURCE A

Extract from a public statement made by the German president Friedrich Ebert, 10 January 1923.

Compatriots!

Based upon military power a foreign nation is about to damage the right

of self-determination of the German people. Again one of Germany’s

adversaries [enemies] invades German territory. The policy of force,

which since the conclusion of peace has been violating the treaties and

trampling [crushing] on human rights, threatens the principal German

economic district, the main source of Germany’s labour, the bread of

German industry and the entire working classes. The French move is a

continuation of wrong and violence and a violation of the Treaty [of

Versailles] aimed at a disarmed nation. Germany was willing to pay

within the limits of its capacity. Without being heard in Paris, it is

going to be attacked.

SOURCE B

Extract from Crisis and Renewal in France, 1918–1962 edited by Kenneth Mouré and Martin S Alexander, 2002.

The allies turned against France in the autumn. Britain had long been haunted by ideas of French predominance [domination] and was now horrified by German collapse. Forgetting that both were temporary conditions, Britain approached the United States about a new reparation inquiry with US involvement; this was granted on an unofficial basis, adding US financial power to British views ... As 1924 began, the Dawes committee set to work, leaving French policy at Anglo–American mercy. Diplomatic isolation, national weariness, and above all financial crisis drove Prime Minister Poincaré from office in June. Others presided over France’s defeat at the London Conference of 1924, where the Versailles Treaty was revised at the insistence of American bankers and British leaders, and led to Locarno in 1925. There Britain succeeded in restoring Germany to equality and itself to the centre of power. When the Locarno Treaties were signed, the Ruhr occupation had ended.

SOURCE C

Cartoon entitled “Into the Arms of the Enemy” by David Low, published in British newspaper The Star, 1923, depicting the French prime minister Raymond Poincaré attacking Germany.

INTO THE ARMS OF THE ENEMY.

“You can do nearly everything with the bayonet – except pick coal.”

A Ruhr Trade Unionist.

“You can do nearly everything with the bayonet – except pick coal.”

A Ruhr Trade Unionist.

SOURCE D

Extract from Grandeur and Misery of Victory, memoirs of French prime minister Georges Clemenceau, 1930.

Extract from Grandeur and Misery of Victory, memoirs of French prime minister Georges Clemenceau, 1930.

When, on 26 September, Germany had given up passive resistance, we were obliged to go back to the system of conferences and meetings of experts. Committees were set up, and were to meet in Paris. But – and this was the great innovation! – the presidency of one of these committees was entrusted to General Dawes of the US, and the president of the second committee was an Englishman, Reginald McKenna.

From the political point of view, the consequences were disastrous. The League of Nations was henceforth to be in charge of the question of disarmament. The United States became the arbiters [mediators] for everything connected with the implementation of one of the most important parts of the Treaty of Versailles, which they had not ratified!

That was tying our hands forever and at the same time surrendering our complete independence, as well as the rights conferred on us by the Treaty of Versailles.

SOURCE E

Extract

from Toward an Entangling Alliance: American Isolationism,

Internationalism, and Europe, 1901–1950 by Ronald E Powaski, 1991.

Ronald E Powaski is an American historian specializing in twentieth

century history.

The Ruhr invasion failed. While France met no military opposition to the occupation, she was condemned by Britain and the United States. Moreover, German passive resistance deprived France of most of the material advantages she had expected.

The Ruhr occupation also hurt Germany. The Germans lost more in revenue [income] from the Ruhr in the nine months of passive resistance than they had paid in reparations in all the years since the war. Further, the complete collapse of the German currency increased agitation from both the extreme left and right and called into question the continued existence of the Weimar Republic.

There was no way the United States could escape the consequences of a German economic collapse. Germany’s inability, or refusal, to pay reparations would make it impossible for the United States to collect war debts from the allies. And Europe’s economic recovery, upon which the vitality of America’s European trade and investments depended, would also prove impossible if Germany’s economy were ruined. Further, an economically and militarily weakened Germany, it was feared, could not serve as an effective barrier against Bolshevism, let alone remain a stable democracy.

1. (a) Why, according to Source D, was the occupation of the Ruhr “disastrous” for France?

[3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source C? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources B and D about the consequences of the occupation of the Ruhr. [6 marks]

3.

With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and

limitations of Source A and Source E for historians studying the Ruhr

Crisis (1923). [6 marks]

4.

Using the sources and your own knowledge, evaluate the impact of the

Ruhr Crisis (1923) on international relations between 1923 and 1929. [8 marks]

November 2013

These sources and questions relate to events in Manchuria (1931–1933).

SOURCE A

Extract from The Rise of Modern Japan by WG Beasley, 1995. WG Beasley is Emeritus professor of the History of the Far East at the University of London, UK.

On the night of 18 September 1931 a bomb exploded on the railway outside Mukden. Troops were immediately moved to seize the city, and by the next morning the occupation of southern Manchuria had begun ... All this had been done, not only against the known wishes of the Japanese cabinet, but also without the authority of the army high command ... On 21 September 1931 China had appealed to the League of Nations, leading to a Japanese denial that she had any territorial ambitions in China and a promise to withdraw her troops. In due course the League appointed a commission of enquiry, chaired by Lord Lytton, whose members arrived in Yokohama early in 1932, to be met almost at once by the announcement creating Manchukuo ... the report they wrote, while cautious and moderate in its tone, left little prospect that the League would not support China. When the matter came finally to debate in Geneva in February 1933, Japan chose to withdraw from the League rather than listen to condemnation.

SOURCE B

Extract from the introduction to The Lytton Report on the Manchurian Crisis, League of Nations Publications, 1932.

Two resolutions were adopted by the Council [of the League of Nations] on 30 September and 10 December 1931. The first one was directed toward the taking of such temporary measures as were deemed essential to prevent any worsening of the situation growing out of the events at Mukden on 18–19 September 1931. The resolution of 10 December 1931 went beyond the scope of the earlier one in that it expressed the desire of the Council “to contribute towards a final and fundamental solution by the two governments of the questions at issue between them”. The Council accordingly decided to appoint a commission of five members “to study on the spot and to report to the Council on any circumstances which, affecting international relations, threaten to disturb the peace between China and Japan, or the good understanding between them upon which peace depends”.

SOURCE C

Extract from “Japan at War: History-writing on the Crisis of the 1930s” by Louise Young, in The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered, 1999. Louise Young is professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US, specializing in East Asian Studies.

One line of academic study on the Manchurian Incident looks at the diplomatic response of the League of Nations and the escalating tensions between Japan and the Western powers, including the American attempt to contain Japan through “moral diplomacy”, the French and British attempts at appeasement, and the appointment of the Lytton Commission, whose critical report resulted in Japan’s withdrawal from the League ... The second set of studies focuses on ... the increasing inflexibility of the Young Marshal [Zhang Xueliang], the fear of the Chinese nationalist movement spreading to Manchuria and dissatisfaction with the civilian authorities’ handling of the Manchurian question. These studies highlight the role of Japan’s garrison force in Manchuria. On the evening of 18 September 1931 several Japanese army officers secretly exploded a section of the Japanese railway, blamed the explosion on Chinese agitators, and used this as a pretext to attack the forces of the Young Marshal.

SOURCE D

Extract from a statement made by Lord Lytton to the British House of Lords, 2 November 1932. Lord Lytton was the chairman of the League of Nations’ Commission of Enquiry into the events in Manchuria.

The first thing I should like to say about the report is that, although it is associated with my name, any value which it may have is due to the fact that it is an international document. In addition to the five Commissioners, who were drawn from five different countries, we were assisted in our work by experts drawn from France, the United States, Holland and Canada, and since our conclusions were unanimous this report may be regarded as the joint work of the nationals of at least seven different countries. I think the report gains in value when we remember that it is the work of the nationals of many different countries. ... At the time of our appointment the governments of both China and Japan undertook at the Council of the League to assist the work of the Commission, and I should like, therefore, to take this opportunity to state publicly that this undertaking was loyally and thoroughly carried out by both the governments. We received from both of them very valuable help.

SOURCE E

Cartoon by Harold M Talburt published in the Washington Daily News, 27 January

1932.

THE LIGHT OF ASIA

1. (a) What, according to Source B, was decided by the Council of the League of Nations at its meetings in 1931? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source E?

[2 marks]

[2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources A and C about events in Manchuria in September 1931.

[6 marks]

[6 marks]

3.

With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and

limitations of Source D and Source E for historians studying events in

Manchuria between 1931 and 1933.

[6 marks]

[6 marks]

4.

Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the significance of

events in Manchuria for China, Japan and the League of Nations between

1931 and 1933.

[8 marks]

May 2014

These sources and questions relate to the aims of the participants and peacemakers: Wilson and the Fourteen Points.

SOURCE A

Extract from a letter by German chancellor Prince Max of Baden to US president Woodrow Wilson, 6 October 1918.

The German government requests the president of the United States of America to take steps for the restoration of peace, to notify all belligerents [adversaries] of this request, and to invite them to delegate diplomats for the purpose of taking up negotiations. The German government accepts, as a basis for the peace negotiations, the program laid down by the president of the United States in his message to Congress of 8 January 1918. In order to avoid further bloodshed the German government requests to bring about the immediate conclusion of a general armistice on land, on water, and in the air.

SOURCE B

Extract from Peacemaking, 1919: Being Reminiscences of the Paris Peace Conference by Harold Nicolson, 1933. Harold Nicolson was a British diplomat who attended the Paris Peace Conference.

[Woodrow Wilson] allowed the whole disarmament question to be limited to the one-sided disarmament of Germany. He surrendered in Shantung, even as he surrendered on Poland. He surrendered over the Rhineland, even as he surrendered in the Saar. On the reparation, financial and economic clauses he exercised no beneficial influence at all, being, as he confessed, “not much interested in the economic subjects”. He allowed the self-determination of Austria to be prohibited. He permitted the frontiers of Germany, Austria and Hungary to be drawn in a manner which was a flagrant [blatant] violation of his own doctrine. And he continued to maintain that his original intentions had not, in fact, been ignored – that in the Covenant of the League could be found the blessings which he had undertaken to provide to the world ... The old diplomacy may have possessed grave faults. Yet they were minor in comparison to the threats which confront the new diplomacy.

SOURCE C

Extract from Europe and the German Question by FW Foerster, 1940. FW Foerster was a German professor at the University of Vienna and a pacifist who opposed German militarism both before and after the First World War.

So far as the spirit of his ideals were concerned, Wilson was certainly right. But he overlooked the fact that these ideas originated in America. He took no account of the realities of Europe, nor of the passions and suspicions provoked by the war. He thought it possible to impose the new order on a Europe still suffering from the war. Clemenceau confronted him with a more realistic language. “The French are Germany’s nearest neighbour and liable, as in the past, to be suddenly attacked by the Germans.”

Wilson cannot be praised too highly in that he called the world’s attention to the necessity of a new international order and pointed out that, without it, no treaty provisions could endure. Without the observance of these [treaty provisions] it would not be long before a second catastrophe overwhelmed Europe.

SOURCE D

Extract from Lessons from History? The Paris Peace Conference of 1919, a lecture delivered by historian Margaret MacMillan at the Vancouver Institute on 1 October 2005.

Woodrow Wilson is sometimes blamed for creating the expectations that ethnic groups should have their own nation states. This again is unfair. He certainly gave encouragement to the idea in his public statements, including the Fourteen Points, but he did not create what was by now a very powerful force. Europe had already seen how powerful nationalism and the desire of nations to have their own states could be with both Italian and German unification. It had already seen how powerful that force could be in the Balkans. Ethnic nationalism and the idea of self-determination for ethnic states was not suddenly created by a few careless words from the American president ... Wilson spoke for many both in Europe and the wider world when he said that a new and more open diplomacy was needed based on moral principles including democratic values, with respect for the rights of peoples to choose their own governments and an international organisation to mediate among nations and provide collective security for its members. He was called dangerously naive at the time and Wilsonianism has been controversial ever since. In the world of 1919, though, when the failure of older forms of diplomacy – secret treaties and agreements, for example, or a balance of power as the way to keep peace – was so terribly apparent, a new way of dealing with international relations made considerable sense.

SOURCE E

Cartoon by Burt Randolph Thomas, published in the American newspaper The Detroit News, 1919, depicting the US president Woodrow Wilson.

HE WAS BOUND TO GET IT WRONG

1. (a) What, according to Source C, were the problems of implementing Wilson’s Fourteen Points? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source E? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources B and D about Wilson and the Fourteen Points. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source C for historians studying the contribution of Wilson’s Fourteen Points to the peacemaking process.

[6 marks]

4. “President Wilson thought he could bring peace to Europe but he succeeded in bringing confusion.” Using these sources and your own knowledge, evaluate the validity of this claim.

[8 marks]

November 2014

These sources and questions relate to the geopolitical and economic impact of the Paris Peace Treaties of St Germain, Trianon and Neuilly on Europe.

SOURCE A JM Keynes, an economist who was a key member of the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, writing in an academic book analysing the Paris Peace

Those readers ... must cast their minds to Russia, Turkey, Hungary, or Austria, where the most dreadful conditions which men can suffer – famine, cold, disease, war, murder, and anarchy – are an actual present experience ... But the opportunity was missed at Paris during the six months which followed the armistice, and nothing we can do now can repair the damage done at that time. Great deprivation and great risks to society have become unavoidable. All that is now open to us is to redirect, so far as lies in our power, the fundamental economic tendencies which form the basis of recent events, so that they promote the re-establishment of prosperity and order, instead of leading us deeper into misfortune.

SOURCE B Carroll Quigley, a professor of History, writing in a survey book on world history, Tragedy and Hope (1966).

The peace settlements made in this period were subjected to vigorous and detailed criticism in the two decades 1919–1939. This criticism was as strong from the victors as from the vanquished [defeated]. Although this attack was largely aimed at the terms of the treaties, the real causes of the attack did not lie in these terms, which were neither unfair nor ruthless, were far more lenient than any settlement which might have emerged from a German victory, and which created a new Europe which was, at least politically, more just than the Europe of 1914. The causes of the discontent with the settlements of 1919–1923 rested on the procedures which were used to make these settlements rather than on the terms of the settlements themselves.

SOURCE C Graham Ross, a lecturer in International Relations, writing in an academic history book, The Great Powers and the Decline of the European States System

1914–1945 (1983).

The Austrian Republic claimed the right to be regarded as a new state and not as the successor of Austria–Hungary but the Allies rejected this argument. Furthermore they prohibited [banned] union with Germany. Austria was thus left in a financially weak position, cut off from her former empire and concerned by the existence of German speaking minorities in the South Tyrol and in Czechoslovakia. There was little she could do about it, however, and the same was true of Hungary. The latter complained bitterly about the loss of territory to Czechoslovakia, Rumania and Yugoslavia which also involved the loss of substantial Magyar minorities to all three. It was precisely their fear of Hungarian nationalism which brought the three states together by various agreements in 1920 and 1921, which became known as the Little Entente.

SOURCE D Raymond Poincaré, president of France between 1913 and 1920, in the opening speech to the delegates at the Paris Peace Conference on 18 January 1919.

The time is no more when diplomats could meet to redraw with authority the map of the empires on the corner of a table. If you are to remake the map of the world it is in the name of the peoples, and on condition that you shall faithfully interpret their thoughts, and respect the right of nations, small and great, to self-determination, and to respect it with the rights, equally sacred, of ethnic and religious minorities ... You will naturally try to ensure the material and moral means of subsistence [economic support] for all those peoples who are created or recreated into states; for those who wish to unite themselves to their neighbours; for those who divide themselves into separate units; for those who reorganize themselves according to their particular traditions; and, lastly, for all those whose freedom you have already agreed to or are about to agree to.

A cartoon of the Paris Peace Conference in the Swiss satirical magazine Nebelspalter

(1919).

At the Peace Conference

At the Peace Conference

“I hope they will soon get through with this Peace Pipe Smoking.

A spark might fall underneath and then – !!!?”

- (a) Why, according to Source C, was Austria dissatisfied with the peace settlement? [3 marks]

-

(b) What message is conveyed by Source E?

[2 marks]

-

Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources B and C about the Paris Peace

Treaties.

[6 marks]

- With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source D for historians studying the Paris Peace Treaties. [6 marks]

-

Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse how successfully the peacemakers

dealt with the challenges facing them upon negotiating the treaties of St Germain, Trianon

and Neuilly.

[8 marks]

These sources and questions relate to Locarno and the “Locarno Spring” (1925).

Source A

The Treaty of Mutual Guarantee between Germany, Belgium, France, Britain and Italy (the Locarno Treaty) (1925).

Article I: The high contracting nations collectively guarantee the maintenance of the territorial status quo resulting from the frontiers between Germany and Belgium and between Germany and France, and the permanent nature of the frontiers as fixed by the Treaty of Peace signed at Versailles on 28 June, 1919.

Article II: Germany and Belgium, and also Germany and France, mutually undertake that they will in no case attack or invade each other or resort to war against each other.

Article III: Germany and Belgium, and Germany and France, undertake to settle by peaceful means and in the manner laid down all questions of every kind which may arise between them and which it may not be possible to settle by the normal methods of diplomacy. Any question with regard to which the nations are in conflict shall be submitted to judicial decision, and the nations undertake to comply with such decision.

Source B

Arthur Rosenberg, a German historian who emigrated to London in 1933, writing in the academic book A History of the German Republic (1936).

The basic idea of the Locarno Pact is that Germany, France and Belgium promise to guarantee their existing frontiers, and refrain from any attempts to alter them by force – an obligation that involved the final renunciation [surrender] by Germany of all claim to Alsace-Lorraine. This renunciation did not involve Germany in any great sacrifice, since after 1919 no serious German politician entertained notions of regaining Alsace-Lorraine ... On the other hand France agreed not to extend her frontiers to the Rhineland by force. Britain and Italy bound themselves in event of an armed violation of the Franco-German frontier to come to the assistance of the attacked Power with their military forces.

The Locarno Pact also anticipated Germany’s entry into the League of Nations and therefore the application of the terms of the Covenant to Franco-German relations. Germany became a member of the League of Nations in 1926 and was formally recognized as a Great Power again.

Source C

“The Highest Point Ever”. A cartoon published in The Columbus Dispatch, a US newspaper (1925).

Source D

G P Gooch, a British historian and politician, writing in the academic book Studies in Diplomacy and Statecraft (1942). The existing frontiers between France and Germany, and Belgium and Germany, were accepted by all three states, and guaranteed by Britain and Italy. We committed ourselves to assist either France or Germany against the unprovoked aggression of the other. It was natural that Poles and Frenchmen, united by a fear of what Germany might do when she recovered her strength, should urge us to guarantee the western frontier of Poland. It was equally natural that we should decline.

Germany seemed resigned to her losses in the west but not in the east. It is true that she signed arbitration treaties with Poland and Czechoslovakia and promised not to attempt to change the Polish frontier by force; but there was no renunciation of claims in the treaty, and no thought of it in German hearts. Our policy may be summarized in a sentence: we guaranteed an accepted frontier, and refused to uphold one which was not agreed.

Source E Anna Cienciala, a Polish-American historian and Titus Komarnicki, who was a Polish politician and lecturer at the Polish School of Political and Social Sciences in London, writing in the academic book From Versailles to Locarno. Keys to Polish Foreign Policy, 1919–1925 (1984).

Stresemann had separated the security problems of Eastern and Western Europe ... As far as Germany’s eastern borders were concerned, Stresemann emphasized that Locarno gave Germany the opportunity of recovering territories lost to Poland. [He] called Locarno an “armistice” and outlined the task for German foreign policy after Germany’s entry into the League: the revision of reparations; the protection of Germans who were living outside the Reich; the “correction” of eastern frontiers – that is the return of Danzig and the Corridor to Germany; a border “correction” in Upper Silesia; and, finally, the union of Germany and Austria ... Stresemann [said] that he had not made any moral renunciation at Locarno, such as the right to make war, since it would be madness for Germany to think of a war with France. So, in return for giving up what he did not possess – the possibility of making war on France – he had obtained many concessions for Germany ... Britain claimed that they had produced a détente on the eastern frontiers of Germany, but the prospects for Poland were dismal.

- (a) What, according to Source A, were the aims of the Locarno Treaty? [3] (b) What is the message conveyed by Source C? [2]

- Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources D and E about the achievements of the Locarno Treaty. [6]

- With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source B for historians studying the “Locarno Spring”. [6]

- “Locarno resulted from a desire for peace on the part of the nations involved.” Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent do you agree with this statement? [8]

Acknowledgments: Blum, J, Barnes, T and Cameron, R. 1970. The European World Since 1815: Triumph and Transition. Boston. Little Brown; Cienciala, A and Komarnicki, T. 1984.

From Versailles to Locarno. Keys to Polish Foreign Policy, 1919–1925. Kansas University Press; Gooch, G. 1942. Studies in Diplomacy and Statecraft. London. Longmans, Green & Co.;

Ozmanczyk, E. 2003. Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements, Vol. 2: G–M (3rd edition). London. Routledge; Rosenberg, A. 1936. A History of the German

Republic. New York. Russell and Russell.

November 2015

These sources and questions relate to the Paris Peace Treaties: Versailles (June 1919).

Source A

Count von Brockdorff-Rantzau, the leader of the German Peace Delegation, in a letter to the president of the Paris Conference, Georges Clemenceau, on the subject of peace terms (May 1919).

We came to Versailles in the expectation of receiving a peace proposal based on the agreed principles. We were firmly resolved to do everything in our power with a view of fulfilling the grave obligations which we had undertaken. We hoped for the peace of justice which had been promised to us.

We were aghast [horrified] when we read in documents the demands made upon us. The more deeply we examined the spirit of this treaty, the more convinced we became of the impossibility of carrying it out. The demands of this treaty are more than the German people can bear ... Germany, thus cut in pieces and weakened, must declare herself ready in principle to bear all the war expenses of her enemies, which would exceed many times over the total amount of German State and private assets.

Source B