Jeremy

Black is a British modern historian and military historian who studied

at the University of Cambridge (Queen's College) and then at the

University of Oxford. He was a lecturer and then professor at the

University of Durham from 1980 and a professor in Exeter from 1996 to

2020. He's been a visiting professor at West Point, Texas Christian

University, and Stillman College and is an Advisory Fellow of the

Barsanti Military History Centre at the University of North Texas, a

senior fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, and has served

on the Council of the Royal Historical Society. He was awarded a Member

of the Order of the British Empire in 2000 for contributions to stamp

design. He specialises in British history, especially the 18th century,

diplomatic history and military history and is the author of over 100

books. The following are links to some of his lectures conducted with The Critic's deputy editor, Graham Stewart, to download, all of which I've listened to and summarised here in order to outline his main arguments.

1. The Meaning of Interpretations of the Past: Narratives about the past—whether personal family histories, national public histories, or academic debates—are shaped by the biases, agendas, and contexts of those constructing them. These narratives often serve to validate contemporary identities, values, or institutions, rather than providing an objective account of historical events. Those who narrate the past, whether individuals or institutions, often present themselves as impartial, but their accounts are inevitably shaped by implicit or explicit biases. This is a theme he explores in his own work, such as Contesting History. He also argues about the functional role of history wherein historical narratives often serve a functional purpose, such as providing identity, meaning, or a sense of continuity between past, present, and future. This is evident in religious narratives (e.g., salvation and redemption) as well as secular ideologies (e.g., communism or Nazi ideology), which Black describes as having a "quasi-sacral" character in their attempt to impose meaning on historical processes.

2. The Meaning of the Historical Process Itself: The question of whether the process of historical change inherently has meaning is more complex and historically contingent. He approaches this question by breaking it down into several key considerations:

- The Vastness of Time: Human history occupies only a tiny fragment of the planet’s existence. For much of this time, there are no written records, and even where records exist, they are limited in their ability to reveal contemporary perspectives. This makes it difficult to assert any inherent meaning in the historical process.

- Religious Frameworks: Historically, attempts to ascribe meaning to the process of history have often been rooted in religious frameworks. For example, Christian narratives, such as those found in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731 AD), frame history as a story of divine intervention, salvation, and redemption. These accounts often served to validate specific institutions, such as the Church, and were disseminated within monastic contexts, though not necessarily to a wider public.

- Secular Narratives: In more recent times, secular ideologies have attempted to provide meaning to history outside a religious context. Black cites examples such as communism and Nazism, which, despite their differences, share a common goal of creating grand narratives to explain historical change. He argues that modern historical writing, even when secular, often retains a "quasi-sacral" character, seeking to derive lessons or impose interpretations that mirror religious frameworks.

3. The Role and Dissemination of Historical Narratives: Black explores how historical narratives have been created and disseminated across time, particularly in pre-modern and modern contexts:

- Pre-Modern Contexts: In the medieval period, historical writing, such as Bede’s work, was often produced within monasteries and served as a tool for religious and institutional validation. These texts were not widely disseminated beyond monastic circles, though they influenced ecclesiastical and political narratives.

- Modern Contexts: With the advent of universities, printing, literacy, and mass communication, the production and dissemination of historical narratives expanded significantly. Black notes that universities, though initially religious foundations, became key sites for historical scholarship, particularly in the 19th century with the rise of source criticism and the German model of historical research. However, he cautions against over-emphasising the distinction between academic and popular history, noting that high-quality historical work has often been produced outside universities, especially in areas like local and regional history.

4. The Purpose of History: Black is critical of the idea that history’s primary purpose is to teach lessons or validate contemporary values. He identifies two contrasting approaches to the study of history:

- Present-Mindedness: Many people approach history as a means of validating their present-day values, identities, or political positions. This is problematic, particularly in contemporary Western culture, where he observes a trend towards "virtue signalling" and "narcissism" in historical discourse, both within and outside academia. He argues that this approach prioritises emotional validation over rational analysis, undermining the intellectual rigour of historical study.

- Understanding the Past on Its Own Terms: We should understand the past in its own context, rather than through the lens of present concerns. While acknowledging that historians are inevitably influenced by their own time, he stresses the importance of recognising the contingency of interpretations and the need for scepticism about imposed meanings.

5. Critique of Contemporary Historical Practice: Black expresses concern about the state of historical study today, both within and outside academia:

- Within Academia: He critiques the narrow specialisation of many academic historians, which he believes leads to a lack of broader contextual understanding. He also notes a trend towards "virtue signalling" in university history departments, where the emphasis on contemporary relevance can hollow out intellectual debate.

- Outside Academia: Black acknowledges the value of historical work produced outside universities, such as by popular historians or local history enthusiasts. He argues that the distinction between academic and popular history is not as sharp as often assumed, and that some of the most innovative and broad-ranging historical work comes from non-academic contexts.

Here Black argues that the common understanding of "war" is too narrow and state-centric, hindering a comprehensive grasp of the phenomenon globally and historically. His main points are:

1. Beyond the State: Defining war solely through the lens of state actors and formal militaries is a culturally specific (Western) and limiting perspective. It ignores organised, large-scale violence perpetrated by non-state entities throughout history and across different cultures.

2. Critique of Eurocentrism: Much of the existing literature on war, even broad overviews, suffers from a Eurocentric or Western-centric bias, neglecting or misrepresenting non-Western military histories and approaches (like those of China or India) unless they fit a Western narrative.

3. Integrating Culture and Technology: The study of military history and war studies should integrate both technological advancements and cultural contexts as independent factors influencing conflict. He criticises the tendency to swing between technological determinism (like the "Revolution in Military Affairs") and purely cultural explanations, especially after Western setbacks.

4. Lessons from the Past - Nuance: Whilst technology changes, strategists can learn from the non-linear nature of war and the frequent disconnect between tactical victories and strategic success (e.g., Hannibal). For soldiers, enduring factors like morale, cohesion, and tactical skill remain relevant across different eras and types of forces (including irregulars).

5. Over-reliance on Limited Theory: There's an over-reliance on a small canon of Western military theorists (like Clausewitz) in military education globally, which may not be sufficient for understanding diverse conflicts or the approaches of non-state actors.

6. China's Distinct Approach: Understanding contemporary powers like China requires recognising their unique strategic culture, influenced by their authoritarian party-state system, which may lead to a different conception and use of force compared to Western models.

7. Complex Diffusion of Military Advancements: The spread of military technology and techniques is not a simple linear process from a "core" to the "periphery." Non-Western societies could acquire advanced weaponry, and victory isn't solely determined by technological superiority. Even within Europe, diffusion was complex and varied, and copying tactics didn't guarantee success against innovative forces like Napoleonic France.

8. Importance of Logistics and Peacetime Preparedness: Often overlooked in popular accounts, logistics and the state of military readiness during peacetime are crucial, particularly for short, intense conflicts. Professor Black here advocates for a more expansive, globally-informed, and nuanced understanding of war that moves beyond state-centric and technology-focused analyses to appreciate the diverse cultural, political, and practical factors that shape conflict across time and space.

Black highlights the evolution of Greek warfare, contrasting the Homeric ideal of individual heroism in the Trojan Wars with the more organised, large-scale conflicts of the classical period, such as the Peloponnesian War. He stresses the importance of cultural and religious values, such as honour and revenge, in motivating conflict. These values were intertwined with religious beliefs, where divine favour or displeasure (as interpreted through oracles) could influence military decisions. The anthropomorphic Olympian gods, though not directly intervening in human affairs, provided a framework for validating conflict and establishing norms. Military innovations, such as the development of tightly packed infantry formations (phalanxes) and advanced naval fleets, marked significant enhancements in Greek military capability. However, Black resists labelling these changes as "revolutions," noting that military practices varied between city-states like Sparta, Athens, and Thebes, each adapting to their unique social and geographical contexts. The Spartan model, often idealised, was not universally applicable, and other states developed distinct military traditions.

Turning to Rome, Black underscores the centrality of logistics, engineering, and adaptability. The Roman military’s success relied on efficient supply networks, road systems, and siegecraft, enabling operations across diverse terrains. Roman tactics favoured close combat, but they struggled against mobile adversaries like horse archers, illustrating the importance of context-specific strategies. The Roman capacity to integrate conquered territories through infrastructure and political control was key to sustaining their empire.

Internal conflict is another critical theme. Black discusses civil wars, slave revolts, and the role of military force in maintaining domestic order, particularly in controlling enslaved populations. He critiques modern misconceptions that downplay the ubiquity of slavery in antiquity, including in Greece and Rome, cautioning against anachronistic moral judgements shaped by contemporary ideologies like decolonisation.

Leadership played a pivotal role in both Greek and Roman warfare. Figures like Alexander the Great exemplified the blend of personal charisma, strategic vision, and direct combat involvement expected of commanders. Roman emperors often rose through military prowess, highlighting the interplay between individual ambition and institutional structures. Black warns against deterministic narratives of decline, such as attributing the fall of Rome to fixed frontiers or internal strife, instead advocating for a focus on specific historical contingencies.

Finally, Black critiques modern scholarly trends that impose rigid frameworks, such as materialist or providentialist interpretations, on ancient warfare. He advocates for a pluralistic approach, recognising the diversity of motivations and practices. The debate over continuity between Roman and post-Roman military systems, he notes, remains unresolved, reflecting broader methodological challenges in historiography. Ultimately, Black’s analysis underscores the need to avoid simplistic analogies or linear narratives, emphasising instead the dynamic, context-dependent nature of ancient warfare. As always, he critiques modern scholarly trends that impose rigid frameworks, such as materialist or providentialist interpretations, on ancient warfare. He advocates for a pluralistic approach, recognising the diversity of motivations and practices. The debate over continuity between Roman and post-Roman military systems, he notes, remains unresolved, reflecting broader methodological challenges in historiography.

1. Feudalism vs. Modern Analogues: Loyalty and Power Structures

- Feudalism as a System: Mediæval European feudalism involved hierarchical loyalty (vassals to lords) tied to land grants and military service. This system was integrated into the political fabric of the state.

- Modern Comparisons: Criminal organisations (e.g., Mexican cartels) or gangs are likened to feudalism in their loyalty structures but differ crucially by operating against the state. Unlike feudal lords, these groups reject state sovereignty, creating parallel power systems.

- Scholarly Tensions: Scholars of medieval Europe may resist such comparisons, but the user argues for their utility in understanding how loyalty and territorial control function in anti-state contexts.

- Feudal vs. Mercenary Forces:

- Feudal Levies: Relied on land grants for service, often inconsistent and tied to social hierarchies (e.g., post-Norman Conquest England).

- Paid Troops: More efficient and direct, as seen in later medieval Europe, where economic yields funded professional soldiers.

- Tactical Adaptations:

- Infantry vs. Cavalry: Effectiveness depended on terrain and technology. Light cavalry excelled in open spaces (e.g., Mongol steppe tactics), while infantry formations (e.g., Swiss pike squares) countered cavalry in constrained environments.

- Archery and Technology: English longbows (Agincourt) and crossbows (Italian city defences) highlight how ranged weapons shaped battlefield dynamics. Defensive tactics often exploited terrain (e.g., wooded areas, fortified positions).

- Global Context: Mongol cavalry’s success stemmed from adaptability, logistics, and horse trade networks—an understudied area ripe for research.

3. Challenging Eurocentrism: Global Military Histories

- Beyond Europe: The user critiques Eurocentric narratives, noting larger-scale conflicts elsewhere (e.g., Mongol invasions of China, Afghan horse-based empires in India). Non-European societies often developed sophisticated military systems overlooked in traditional scholarship.

- Naval Warfare: Mediterranean naval battles (e.g., Venetian conflicts) and coastal sieges illustrate how maritime power intertwined with land strategies, emphasising bombardment and troop deployment.

4. Contextual Nuance Over Universal Models

- Terrain and Resources: Mountainous regions (e.g., Swiss Alps) favoured nimble infantry, while plains enabled cavalry dominance. Protective gear (or lack thereof) influenced combat styles (e.g., shieldless agility vs. armoured shock troops).

- Skill vs. Technology: Hunting cultures (e.g., Japanese archers, African projectile users) leveraged existing skills, while urban militias relied on institutional training (e.g., crossbowmen in Milan).

- Capability Gaps: Military success hinged on maintaining technological or tactical edges (e.g., English longbow dominance eroded as French artillery and leadership improved post-1430s).

5. Revisiting Historical Narratives

- Norman Conquest: Often framed as a radical rupture (e.g., Domesday Book), but continuity existed in England and elsewhere. Feudal practices coexisted with paid service and gradual institutional shifts.

- Inevitability Myths: Outcomes like the Hundred Years’ War were not predetermined but shaped by leadership, disease, and tactical choices (e.g., French adapting to English defensive strategies).

He goes on to question the portrayal of Prussian rulers, including the Great Elector, as exceptionally successful military leaders, suggesting they were similar to other European rulers of the time who sought validation through military victories. Black argues that Frederick the Great's achievements were perhaps ephemeral, heavily reliant on military success which proved variable. While successful in his early wars, Frederick's performance in the Seven Years' War was mixed, with costly battles and failures against the Austrians, who developed better artillery. His later campaign in the War of the Bavarian Succession was also unsuccessful.

Black suggests Prussia wasn't as comparatively impressive as often portrayed, particularly when compared to Russia under Peter the Great or even Austria, which expanded significantly in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. He highlights periods when other German powers were more concerned about Austria's strength. Prussia's vulnerability is underscored by Russian occupations of Berlin and the movement of Russian armies through Germany during various conflicts.

Regarding Prussian policy, Black notes that efforts to build the economy through skilled immigration and protectionism were standard mercantilist practices of the time, not unique to Prussia. He questions the idea of Prussia's early rise by pointing to the successes of other North German states like Hanover, which gained the British throne, and Saxony, which briefly held the Polish throne. He refers to the description of Prussia as the "sandbox of Europe" due to its poor soil and limited agricultural productivity, suggesting military service was a key avenue for the landowning gentry to gain wealth and status. Black argues that Prussia's economic and industrial base was relatively weak, with significant industrial areas only acquired later through conquest. He suggests this might explain Prussian envy towards more cultured and prosperous states like Saxony, evidenced by the bombardment of Dresden. He disputes the notion that Prussia was significantly more centralised than other major German states. The ruler's authority varied across different territories. Black posits that Britain, with its unified Parliament after the union with Scotland, was arguably more centralised, enabling it to raise revenue effectively and support a powerful Royal Navy, whose reach and capabilities far exceeded those of Frederick's land-based army operating within a limited European theatre.

Black criticises the tendency to overstate Frederick's military genius, pointing out his limited experience compared to figures like Wellington who operated across continents and faced diverse challenges. He suggests that war often weakened states, citing the damage to Prussia after the Seven Years' War and in subsequent conflicts. He argues that Frederick's decision to repeatedly engage in wars, rather than using his army as a deterrent, brought considerable devastation to Prussia. The state's survival was arguably due to fortunate circumstances, such as the death of Empress Elizabeth of Russia and the accession of the pro-Prussian Peter III.

Black concludes that Prussia in the eighteenth century may not have been a great power or necessarily possessed the inherent qualities to become one. This perception, he suggests, is a retrospective reading influenced by nineteenth-century perspectives seeking a historical precedent for German unification under Prussia. He points to the significance of the Great Northern War in boosting Hanover's position more than Prussia's. He highlights the ongoing tension in Prussian policy regarding its relationship with Russia, fluctuating between seeking alignment and forming anti-Russian coalitions. Black suggests Frederick's anti-Austrian policy was detrimental to Prussia and potentially weakened Germany against external threats like France and Russia. He criticises the lack of comprehensive and critically comparative historical accounts of Frederick the Great, particularly in English-language scholarship, which he feels often praises Frederick without sufficient context or strategic understanding.

Finally, Black touches upon the concept of a "Third Germany," distinct from Austria and Prussia, which emphasised consensual governance within the Holy Roman Empire and provided mechanisms to challenge rulers perceived as abusive. He suggests this perspective offered an alternative to the bipolar view of German history dominated by the Austro-Prussian rivalry, a rivalry which, combined with French intervention, arguably undermined a potentially more stable system. He also notes the role of religion, with a sense of strong Protestant opposition to Catholic powers, but argues that in the early eighteenth century, Bavaria was a more significant opponent to the Emperor than Prussia. He concludes by reiterating that Frederick the Great's commitment to an anti-Austrian policy was a long-term burden for Prussia and a source of weakness for Germany.

He highlights that France in the 18th century was domestically stable and prosperous compared to previous periods, lacking large-scale uprisings or urban unrest. While acknowledging the rise of Russia and Austria potentially limited French influence internationally, he sees France as relatively successful up to the revolution.

Black believes the revolution wasn't inevitable and wasn't initially intended to overthrow the monarchy entirely. He sees the early stages as an attempt to reform and reinvigorate the existing system, addressing financial issues and seeking greater consent for taxation, rather than starting anew. He likens the situation to earlier periods of upheaval in England, suggesting a political breakdown due to mistrust between the monarchy and other power centres, specifically regarding financial reform, which led to the summoning of the Estates-General. He emphasises the rapid pace of change and lack of established constitutional mechanisms as key factors in the revolution's descent into radicalism.

Regarding whether the revolution could have succeeded without the Terror, Black implies that it was possible but unlikely given the context. He suggests Louis XVI's mismanagement, particularly his perceived untrustworthiness and the flight to Varennes, worsened the situation. However, he stresses that the outbreak of war with Austria in 1792 was a crucial turning point. This international crisis fuelled paranoia about internal enemies and empowered more radical factions. Black argues that French policy itself contributed to the war's outbreak, particularly concerning pre-existing treaties and territories bordering France. The war, rather than inherent revolutionary violence, is presented as a major driver towards the Terror. He contests the view of the Terror as primarily a class war, noting that many victims were ordinary people, and argues the violence of the revolution created lasting divisions in France.

France was profoundly reshaped by the revolution, though not necessarily in a permanently republican direction initially. The revolution was followed by the Directory, then Napoleon's dictatorship, and subsequent restorations of the monarchy. Black argues that the repeated shifts in regime demonstrate that the revolution's outcome was not a straightforward triumph of republicanism. However, he acknowledges the revolution did plant seeds of republicanism that re-emerged later in French history. The revolutionary period left a complex legacy, marked by political divisions and differing interpretations of its various phases – the early revolution, the Terror, the Napoleonic era. The revolution's impact was further shaped by subsequent events in French history, including international relations, urbanisation, industrialisation, and new political movements. Black views Napoleon as a figure who emerged from the revolution but ultimately created a dictatorship and engaged in prolonged wars with heavy human costs. He criticises the mismatch between revolutionary rhetoric and the reality of Napoleonic power, particularly highlighting the extensive use of conscription which was a novel and impactful feature of the period. He notes the surprising lack of popular resistance to Napoleon's downfall in 1814 and 1815, suggesting the revolution's popular base might have been shallower than sometimes portrayed. He concludes with a cautionary message about violence in revolutions, arguing that while fighting for values can be necessary, it's also crucial to consider whether prioritising ideological purity over compromise can lead to detrimental outcomes.

Black challenged the idea that the French Revolutionary Wars marked a significant shift towards more intense or effective warfare, arguing instead that the French military's resilience and adaptability were key factors in their success. He also highlighted the importance of logistics and the role of looting and conquest in supporting the French military effort.

The lecture also touched on the role of Britain in the wars, with Black arguing that the British navy was crucial in providing security for the British Isles and protecting British trade. He also discussed the various coalitions that formed against France, including the second coalition, which included Russia, Austria, and Britain. Black argued that Napoleon's basic concerns were prestige and a desire for military glory, and that he was willing to take significant risks to achieve these goals. He also discussed the limitations of Napoleon's power, including his lack of control over the weather and the difficulties of maintaining a large army in the field. Black finally concluded with a discussion of the aftermath of the wars, including the Congress of Vienna and the reorganisation of Europe that followed. Black argued that the period of relative peace that followed the wars was not solely due to the exhaustion of the major powers, but also reflected a new-found appreciation for the need for restraint and diplomacy in international relations.

Napoleon's empire had a system of expropriation and provincial autonomy, making it more powerful than its predecessors. France had an overseas empire, but Napoleon's regime was not as expansionist as the Republican regime from 1792. Napoleon destroyed the Republic, which angered many Republicans. Judging Napoleon should consider his overthrow of the Republic rather than his own overthrow. France has varied views on Napoleon, reflecting a contesting of national narratives. In the 19th century, Napoleon was a contentious figure, and his nephew, Napoleon III, also destroyed a republic. The Third Republic had no reason to love Napoleon. Some radicals still viewed Napoleon positively, but others worried about the idea of a leader seizing power.

Napoleon's will to power is criticised by Black, and his military victories provided only short-term solutions. His success was fragile, and his actions were not justifiable. Napoleon's regime is compared to Hitler's, highlighting the dangers of worshipping a will to power. Napoleon's military prowess is praised, but his strategic failures, particularly in the Battle of Waterloo, are noted.

Black also discusses the commemoration of Napoleon and the French Revolution, highlighting the complexities of defending historical figures. President Macron's defence of Napoleon is seen as nuanced, whilst Mitterrand's commemoration of the French Revolution is criticised for its simplistic portrayal (Black clearly despises Mitterand). The lecture concludes by noting the irony of justifying the Revolution's violence and disruption, similar to the justifications used for communist regimes in Eastern Europe. Many French people resisted the Revolution, highlighting the complexities of French history.

The lecture also explores the historical Franco-Ottoman alliance, dating back to the 16th century, as a counterweight to various European powers, including Russia, which France viewed as a fundamental threat to European stability, often portraying Russia as a barbaric, non-Western society. Britain’s involvement, while partly influenced by its alliance with France, was also driven by concerns over Russian expansionism, though Professor Black questions whether British interests truly lay in defending the Ottoman Empire or if the conflict reflected a failure to prioritise more pressing strategic concerns. The Crimean War, he argues, was strategically misconceived, lacking a clear purpose or effective implementation, and was marked by significant logistical and tactical failures, particularly on the British side, though these were not uncommon in early stages of British campaigns historically.

Professor Black concludes by drawing parallels to modern conflicts, cautioning against the dangers of engaging in wars over secondary priorities without adequate risk analysis, as this can misconfigure military resources and neglect more significant threats. He underscores the importance of learning from historical failures of statecraft, such as those evident in the Crimean War, to avoid similar mistakes in contemporary international relations.

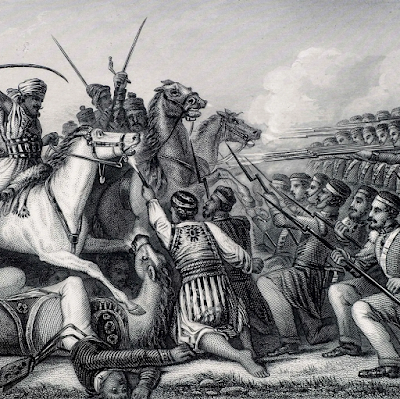

Black highlights the Company’s alliances with local Indian rulers, which provided additional manpower, particularly cavalry, addressing a key weakness in the Company’s forces. He distinguishes between Indian soldiers directly employed by the Company and those from allied states, over whom the Company had little control. He also notes the presence of British and other European soldiers in the Company’s ranks, often at junior levels, and cautions against oversimplified historical narratives that ignore India’s ethnic, religious, and geographical diversity or conflate British India with modern nation-states like Pakistan and Bangladesh.

On the nature of conflicts, Black explains that the British fought both European rivals, such as the French, and Indian powers, but these were often interconnected, as both European powers allied with local rulers. He describes the frequency of conflict as varying by presidency and scale, with periods of relative calm interspersed with major campaigns, such as those against Mysore in the 1790s and the Marathas in the early 1800s. He also points out that some major regional powers, like the Persians and Afghans, did not directly engage the British during their invasions of India in the 18th century.

Regarding the Indian Mutiny of 1857 itself, Black frames it as a significant but contained crisis, not a strategic threat on the scale of, for example, the American War of Independence. He notes that while it began as a military mutiny within the Bengal Army, it escalated into a broader uprising, though not all Indian troops rebelled—about 30,000 of the 135,000 Indian soldiers in the Bengal Army remained loyal. The mutiny was triggered by the use of greased cartridges for the new Enfield rifle, offensive to both Hindu and Muslim soldiers, though Black suggests this issue was likely exaggerated due to existing tensions. The British response was rapid, bolstered by loyal Indian troops and reinforcements from elsewhere, and by mid-1858, the uprising was largely suppressed, though sporadic fighting continued.

Black critiques attempts to portray the mutiny as a proto-nationalist movement, arguing that such interpretations reflect post-independence narratives rather than historical realities. He questions what independence would have meant in 1857, given India’s diversity and the lack of a unified national identity, and warns against oversimplified accounts that ignore the brutality on both sides, including atrocities against civilians. He also discusses the aftermath, noting the British Army’s takeover of the Company’s military role, a process influenced by growing security demands in South Asia, financial pressures, and concerns about Russia, though he cautions against viewing this as inevitable, emphasising the role of contingency in historical outcomes. Throughout, Black stresses the need for nuanced historical analysis, avoiding narratives that serve modern political agendas or flatten the complexities of empire, conflict, and identity in India.

The war emerged from long-standing tensions in the federal union. While slavery was a central issue, other regional, economic and political factors contributed to the conflict. After Lincoln's election, South Carolina seceded in December 1860, with other Southern states following to form the Confederacy. The war began when South Carolina attacked Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Lincoln's subsequent call for 75,000 volunteers prompted additional states (Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas and North Carolina) to join the Confederacy, significantly strengthening its position.

Black emphasises that although the North possessed superior manpower, industry, transportation and finances, this advantage did not guarantee victory. The Confederate strategy mirrored that of the American Revolution: maintain a presence in the conflict to increase the North's costs, establish international legitimacy and potentially secure foreign intervention. The South did not need to conquer the North; it merely needed to avoid defeat until Northern resolve weakened. The Union's initial strategy, known as the "Anaconda Plan," involved blockading Southern ports and controlling the Mississippi. However, Northern strategy faced internal tensions, particularly regarding the treatment of Southern civilians and the balance between eastern and western operations.

Black identifies the 1864 presidential election as the decisive turning point, arguing that had Lincoln lost to Democratic candidate George McClellan, the North might have pursued peace negotiations. Lincoln's victory ensured the war would continue until Confederate surrender.

Naval power played a crucial role, with the Union developing the world's second most powerful navy to blockade Southern ports. The lecture also addressed the potential for British intervention, which posed a serious risk in 1861-62 but never materialised.

The war concluded when Confederate generals surrendered their armies rather than following Jefferson Davis's call for guerrilla warfare. Black suggests that while Confederate victory was possible earlier in the war, Lincoln's re-election and the final six months of campaigning made Southern defeat increasingly inevitable. At the strategic level, civilian governments directed the war on both sides, while generals controlled operational matters, often with poor coordination. The length of the conflict reflected not just military limitations but also the fundamental strategic asymmetry between North and South.

Regarding Prussia's role, Black argues that its emergence as the leading German state resulted from a combination of military strength, economic development, and strategic leadership. He particularly emphasises the modernisation of the Prussian army and bureaucracy as crucial factors, rather than focusing solely on Bismarck's diplomatic manoeuvres.

On Bismarck himself, Black presents a nuanced view. Whilst acknowledging Bismarck's tactical brilliance, he argues that the Chancellor worked within existing constraints and opportunities rather than single-handedly engineering unification. Bismarck's pragmatic approach to power politics, including his willingness to use both conservative and nationalist forces for Prussian interests, is presented as crucial but not all-determining. The three wars of unification (against Denmark, Austria, and France) are analysed not just as military conflicts but as carefully orchestrated diplomatic events. Black argues that each conflict served multiple purposes: demonstrating Prussian military superiority, isolating potential opponents, and gradually building support for Prussian leadership among other German states.

The creation of the German Empire in 1871 is presented as a compromise between different interests. Black emphasises that the federal structure of the new Reich reflected the need to balance Prussian dominance with the autonomy desires of other German states. This federal arrangement would later prove both a strength and a weakness of the new nation. Black pays particular attention to social and cultural factors in unification. He argues that the growth of a German national consciousness through education, literature, and shared cultural experiences was as important as political and military events. The role of the middle classes in supporting nationalism and modernisation is highlighted as crucial.

Regarding the international context, Black emphasises how German unification fundamentally altered the European balance of power. He argues that the creation of a powerful central European state had long-lasting implications for international relations, leading to new alliance systems and eventually contributing to the tensions that led to World War I.

The professor also addresses the historiographical debates surrounding unification. He challenges both the traditional nationalist interpretation that saw unification as inevitable and revisionist views that focus exclusively on Prussian military power. Instead, he advocates for understanding German unification as a complex process involving multiple factors and actors.

Black concludes by discussing the legacy of unification for modern Germany. He argues that the manner of unification - through Prussian military strength rather than liberal constitutionalism - had significant implications for German political development. The federal structure established in 1871 continues to influence German governance today. The significance of German unification, in Black's view, extends beyond German history. He presents it as a crucial case study in nation-building, demonstrating how various factors - military power, economic integration, diplomatic skill, and cultural identity - can combine to create a modern nation-state. This process, he argues, has important lessons for understanding nationalism and state formation more broadly.

Black also examines the motivations behind the Scramble for Africa, particularly in the 1880s and 1890s, suggesting that economic returns from colonial control were often low compared to free trade. He highlights competition among European powers, such as France, Britain, Germany, and Italy, as a driving force, rather than purely economic or ideological factors. This competition was not unique to Africa, as similar dynamics played out in Asia and the Pacific. For example, British expansion into Egypt and Sudan was partly to counter French ambitions, while French moves into Tunisia aimed to pre-empt Italian influence. African powers, such as Egypt and the Mahdi in Sudan, also demonstrated dynamism, though they lacked the military capacity of non-European powers like Japan.

The lecture considers why European powers pursued imperial annexation rather than continuing to rely on local rulers, as they had in places like Egypt and Morocco. which he suggests was partly opportunistic, as seen in Britain’s acquisition of shares in the Suez Canal, and partly driven by competition among European powers. Different interest groups within European countries, such as missionaries, anti-slavery movements, and commercial lobbies, also influenced the process, though their goals often conflicted. For instance, French ambitions in Algeria focused on settlement and military recruitment, whilst in West Africa, the emphasis was on smaller forces and local recruitment without large-scale settlement.

Finally, Black addresses the role of slavery in the narrative of European imperialism, challenging the oversimplified view of slavery as a solely European imposition on Africa. He notes that slavery existed within African societies and that European powers, whilst often hypocritical, did attempt to suppress the slave trade, though with limited success. The lecture concludes by reflecting on the diplomatic efforts, such as the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, to regulate the Scramble for Africa, though these efforts may have encouraged further expansion by legitimising claims based on effective occupation. Overall, Black presents the Scramble for Africa as a complex process driven by competition, opportunism, and diverse interest groups, rather than a simple story of technological or military superiority.

Black explains that the Boers, despite being outnumbered and less technologically advanced, effectively utilised their knowledge of the terrain, long-range rifles, and guerrilla tactics to resist British forces. The British initially struggled due to the Boers' ability to wage a mobile, defensive war, exploiting their familiarity with the landscape and accurate marksmanship. The Boers' early successes, such as the defeat of British forces at Majuba Hill in 1881, demonstrated their tactical prowess. However, the British adapted by deploying larger forces, employing scorched-earth policies, and establishing concentration camps to suppress the Boer insurgency. He argued that the conflict in South Africa was not an entirely new kind of warfare but rather an adaptation of earlier imperial conflicts. Like previous struggles on the empire’s periphery, the war was driven by competition for strategic resources such as diamonds and gold, and by the broader ambitions of the British Empire in securing vital routes to India and maintaining influence in the region. The war also reflected the challenges that large empires face when fighting on multiple fronts, as the British were simultaneously dealing with crises in other parts of their empire, such as Egypt. The conflict ultimately ended with the British victory in 1902, but it had significant consequences. For South Africa, it led to the integration of the Boer republics into the British Empire, though native African communities remained marginalised. The war also influenced perceptions of British military capabilities, showcasing both their resilience and the challenges of combating guerrilla warfare. Black concludes that whilst the conflict did not introduce entirely new methods of warfare, it underscored the importance of adaptability and the complexities of imperial conflicts.

emphasised that the British military was not merely a defensive institution, but a proactive expeditionary force capable of conducting complex overseas operations. The Royal Navy, in particular, was crucial in projecting British power, providing maritime supremacy that allowed for rapid troop deployments, supply lines, and strategic interventions worldwide.

Black discussed how the military's organisational structure enabled rapid mobilisation and adaptability. Regiments were strategically positioned across colonial territories, allowing quick responses to local conflicts, rebellions, and potential challenges to imperial control. The army's experience in diverse geographical environments, from the scorching deserts of Africa to the mountainous regions of India, contributed to its effectiveness.

The lecture also touched on technological advancements that enhanced military capabilities, such as improved weaponry, steam-powered ships, and more efficient communication systems. These innovations gave British forces significant advantages in conflicts against indigenous populations and rival European powers.

Expeditionary campaigns were a key focus, with Black highlighting notable military engagements in regions like India, Africa, and the Middle East, where British forces conducted military operations to secure territorial interests and suppress local resistance to colonial expansion. The presentation underscored how the military was not just an instrument of territorial conquest, but also a tool for maintaining imperial prestige, protecting trade routes, and implementing British geopolitical strategies during the Victorian era.

In the Spanish-American War, the main theatres of conflict were the Philippines and Cuba, where the United States, a rising industrial power, sought to expand its influence at the expense of Spain, a declining imperial power. In the Philippines, this led to a successful American takeover, followed by a struggle against native peoples, highlighting early 20th-century cultural and ideological clashes between a modernising America and what was perceived as a backward Islamic society. In Cuba, American intervention was driven by a mix of strategic interests and public opinion, fuelled by the yellow press, which limited the government’s room for manoeuvre. Spain, despite its weakened position, resisted surrendering its empire due to ideological and military ethos, demonstrating that non-rational factors often drive conflict.

The Russo-Japanese War, fought primarily in the waters of Korea, China, and Manchuria, similarly reflected competition between a rising Japan and an expanding Russia. Japan’s victory was facilitated by its modern navy, built with British expertise, and decisive naval battles, such as those in the Yellow Sea and Tsushima. On land, the war featured trench warfare, machine guns, and other technologies later seen in the First World War, though Japan’s inability to force a Russian surrender highlighted the limits of its power. Russia’s defeat was compounded by internal unrest, partly instigated by Japanese intelligence, and a loss of confidence following naval losses. Both sides were influenced by a mix of rational interests, such as territorial expansion, and irrational factors, including racist views of opponents.

Black also explores the broader context of these wars. In the Spanish-American War, the United States saw itself as a rising power fulfilling a progressive destiny, while Spain’s decline was evident in its inability to suppress Cuban insurgents. The explosion of the USS Maine, though not necessarily the sole cause, escalated tensions towards open conflict. In the Russo-Japanese War, Japan’s modernisation, often linked to the Meiji Restoration, enabled it to challenge Russia, though Black cautions against oversimplifying this narrative. Both conflicts were shaped by power competition over weakening regions, such as Cuba and Manchuria, and by opportunities arising from the opponent’s vulnerabilities.

The lecture also considers the wars’ legacies. The Spanish-American War established the United States as a two-ocean power, with control over the Philippines and an informal economic colony in Cuba, while avoiding the high costs of traditional empire-building. The Russo-Japanese War marked Japan’s emergence as a modern power, though its lessons, such as the importance of willpower and decisive battles, were sometimes misapplied in later conflicts. Black notes that military lessons from these wars, particularly the Russo-Japanese War, influenced First World War strategies, though often through the filter of existing doctrines and strategic cultures.

Finally, Black highlights the role of mediation, such as the Treaty of Portsmouth, facilitated by the United States, which positioned itself as a neutral Pacific power. This reflected America’s growing global influence, though Japan felt its gains were limited by international intervention, as it had in 1895 after defeating China. Overall, Black argues that these wars remain relevant for understanding the interplay of power, ideology, and technology in shaping international conflicts.

The lecture also touches on the origins of British geopolitical theory, particularly through the work of Halford Mackinder, whose 1904 paper on the Asian heartland framed global power struggles as a contest for control of this pivotal region. Mackinder’s ideas, which saw Britain as a peripheral power resisting Russian dominance, are linked to later geopolitical anxieties, such as fears of a Russo-German alliance, and even to NATO’s strategic concerns during the Cold War. Addressing the British perspective, Black notes that post-1857, after the Indian Mutiny and the replacement of the East India Company with direct British rule, there was heightened concern about defending India, particularly against perceived Russian threats via Afghanistan. This anxiety was not just about direct invasion but also about Russia’s potential to destabilise the region by supporting local powers. The lecture draws parallels with modern geopolitical uncertainties, such as Russia’s intentions in Ukraine, suggesting that historical fears of Russian expansionism were often more about strategic pressure than outright conquest.

Black also responds to questions about the role of Persia, the impact of German involvement before the First World War, and the significance of the 1907 Anglo-Russian agreement, which divided spheres of influence in Persia and reduced tensions over Afghanistan. He argues that while this agreement marked a shift, the Great Game’s dynamics persisted, particularly through the Russian Civil War and into the 20th century, with cultural echoes in British literature and media. Overall, Black underscores the complexity and continuity of Eurasian geopolitics, challenging simplistic narratives of Anglo-Russian rivalry and highlighting the interplay of multiple powers across centuries.

Black emphasises the volatile nature of German society during this period, marked by rapid industrialisation, secularisation, democratisation, and nationalism. He notes the growing divide between the industrial west and the agrarian east, where the military elite held significant power. This elite, rooted in landownership, feared the rise of socialism and working-class activism, using militarism to defend their privileges. Black contrasts Germany's political system with Britain's, arguing that Germany lacked genuine democratic control, with the Kaiser and his chancellors wielding substantial executive power.

The professor critiques the idea that Germany was a democracy, pointing out that while it had universal male suffrage, the government remained largely unaccountable to the legislature. He highlights the short-lived nature of ministries under Wilhelm II, which prevented effective restraint on the Kaiser's ambitions. Black also discusses the role of the military, which absorbed vast resources and played a central role in shaping Germany's aggressive foreign policy.

In terms of foreign policy, Black argues that Germany's leaders exaggerated the threat posed by Russia and France, contributing to a sense of encirclement. He suggests that Germany's actions, particularly its naval buildup and aggressive diplomacy, provoked tensions with Britain and other powers. Black criticises the notion that war was inevitable, arguing that more sensible leadership could have averted catastrophe.

Black draws parallels between Wilhelm II and Hitler, noting similarities in their personalities, policies, and the destabilising effects of their leadership. He also discusses the influence of geopolitical theories, such as Ratzel's concept of "Lebensraum," which justified expansionism and militarism. In his conclusion, Black urges listeners to reflect on the dangers of foolish leadership, drawing parallels between Wilhelm II's Germany and contemporary international crises. He emphasises the importance of understanding historical contingencies and the unpredictable consequences of actions, particularly in the context of aggressive, militaristic leadership.

The discussion begins by revisiting pre-war geopolitical theories, such as Mackinder’s concept of the Eurasian pivot and heartland, and their relevance to the First World War. Black highlights the German Berlin-to-Baghdad railway project, which was seen as a strategic move to challenge British dominance, particularly in India, and to extend German influence through the Ottoman Empire. Contemporary observers, such as Fraser, viewed this railway as a potential threat to British prestige and a source of geopolitical tension, though its incomplete state limited its impact during the war. Whilst it facilitated some troop movements within Anatolia, it did not shape overall strategy or operations. Black contrasts the speculative focus on grand transcontinental rail projects, such as the Berlin-to-Baghdad line or the Trans-Siberian railway, with the practical importance of domestic rail networks. For instance, France’s rail system enabled rapid troop redeployments during the 1914 Marne offensive, and Britain’s rail infrastructure supported its military-industrial mobilisation. These domestic systems proved far more significant than the grandiose geopolitical visions of transcontinental connectivity.

The lecture also critiques German geopolitical strategy during the war. Germany’s initial concerns about Russia led to a heavy troop deployment in the east, but these fears proved unfounded as Russia weakened after 1914, especially following the 1917 revolutions. Germany’s eastern victories, achieved at relatively low cost, contrasted sharply with its prolonged and ultimately unsuccessful western campaign. Black notes that German geopolitical assumptions, such as underestimating the consequences of bringing Britain and the United States into the war, were flawed and poorly executed, revealing a disconnect between strategic planning and operational realities.

The discussion extends to post-war geopolitics, particularly Mackinder’s proposals for buffer states to contain Soviet expansion and his involvement in the Russian Civil War. Black critiques Mackinder’s ideas as overly idealistic, pointing to the failure of foreign interventions in Russia due to the weaknesses of anti-communist forces and the broader exhaustion following the First World War. Britain’s withdrawal from the Caucasus, for example, reflected the impracticality of maintaining control over distant regions amidst financial constraints and competing imperial commitments in places like Ireland, Iraq, and Egypt. Black also contrasts Mackinder’s idealism with Lenin’s more pragmatic, yet equally ideological, vision of geopolitics, which saw colonial regions as a vulnerable underbelly of Western powers. Both perspectives, however, are critiqued as somewhat detached from practical realities. The lecture concludes by reflecting on the limitations of geopolitical theorising, such as Mackinder’s unrealistic proposals for Anglo-American naval cooperation, and underscores the importance of grounding strategic planning in operational and logistical realities rather than abstract map-based speculation.

Throughout, Black emphasises that geopolitical outcomes, such as the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939–1941, were not inevitable but arose from specific historical contingencies, further challenging deterministic views of geography and power.

2. Relative Stability in the Mid-1920s: Despite early violence and extremism (suppressed by the army and authorities, as seen with the failed communist uprisings and Hitler's 1923 putsch), the mid-1920s saw a degree of stabilisation. This included diplomatic normalisation with the Locarno Treaty (1925) and Germany joining the League of Nations (1926), alongside social welfare improvements like unemployment insurance (1927). He warns against buying into Nazi propaganda that retrospectively painted the entire period as chaotic.

3. The Great Depression as a Turning Point: Whilst inherent problems existed (like the relationship between regions and the centre, and the influence of extremist parties), the extreme instability and misery often associated with Weimar are more a consequence of the Great Depression from 1929-1930 onwards. The collapse of the Müller government in 1930 due to its inability to handle rising unemployment demonstrates the impact of this external shock.

4. Authoritarian Democracy but Instability: The political system's shift towards presidential emergency decrees under Brüning, appointed by Hindenburg, represented a move towards an "authoritarian democracy." However, Prof. Black suggests the real problem was the instability of this authoritarian system, rather than the authoritarianism itself being unique to the period.

5. Cultural Dynamism: The cultural vibrancy of the Weimar era (Bauhaus, Kurt Weill, Expressionist film, etc.) demonstrates the diversity and dynamism of German society and shouldn't be dismissed as merely a distraction.

Thus in this lecture, Prof. Black argues for a more nuanced view of the Weimar Republic, emphasising that many of its problems were common to post-WWI Europe, that it achieved a degree of stability in the mid-1920s, and that the economic crisis of the Depression was a critical factor in its eventual destabilisation, rather than an inevitable trajectory from its inception.

Professor Black's lecture discusses the rise of Hitler and the Nazi party in Germany during the 1930s. He highlights the complexities of historical interpretations and the different levels of analysis that can be applied to this period, arguing that there are two main approaches to understanding the rise of Hitler: one that focuses on the actions and intentions of a small group of politicians, and another that looks at the broader societal and economic factors that contributed to the Nazi party's success.

Black notes that the Nazi party's popularity grew significantly during the 1930s, with the party winning 37% of the vote in the 1932 election. He suggests that this was not just a result of the party's extremist ideology, but also due to its ability to tap into the frustrations and discontents of the German people, particularly in the context of the Great Depression. The professor also discusses the role of other political parties and leaders during this period, including the Centre Party, the Communist Party, and the conservative politician Franz von Papen. He notes that the Nazi party was able to exploit the divisions and weaknesses of these other parties, and that the conservative elite in Germany was willing to collaborate with the Nazis in order to prevent a communist takeover. Black argues that the rise of Hitler was not just a result of the actions of a small group of individuals, but also due to the broader structural and economic factors that were at play in Germany during the 1930s. He suggests that the Nazi party's success was facilitated by the weaknesses of the Weimar Republic, including its proportional representation system and the lack of a strong, unified opposition to the Nazis. The professor also touches on the role of Hindenburg, the President of Germany, in the rise of Hitler. He notes that Hindenburg was a key figure in the appointment of Hitler as Chancellor, and that he was willing to grant Hitler significant powers in order to stabilise the government. Black suggests that Hindenburg's actions were motivated by a desire to prevent a communist takeover, and that he underestimated the threat posed by the Nazi party.

Nazi popularity stemmed partly from the promise of restoring German greatness and improving social mobility and employment. Their ideology had a populist appeal, including a distinct anti-Semitism, and promoted a nationalistic vision of a German community excluding those deemed outsiders. Propaganda, spectacles, and the cult of personality around Hitler all contributed to Nazism functioning as a kind of civic religion for many Germans. Whilst there was a failed plot against Hitler in 1938, by late 1934, options for a different political direction were largely closed off. Some in Germany saw Fascist Italy as a positive example, though the lecturer notes fundamental differences. It's incorrect to assume British Conservatives were sympathetic to Nazism; their values were fundamentally opposed. Despite appearing a one-man state, there were always some checks on Hitler's power. The Nazi state was chaotic, with competing factions and individuals pursuing their own agendas. This internal chaos, ironically, created some limitations on centralised control, as Nazi agents would often resist each other. The Nazi state was also inefficient and brutal, similar in some ways to the Soviet Union, though Soviet brutality was even more extreme and systematic. Ultimately, the Nazis' racial ideology was self-destructive. It's important to acknowledge that extreme messages were popular in the 1930s, boosted by economic and social hardship. Many who previously supported democratic parties became sympathetic to Nazism. The Nazis suppressed opposition brutally, targeting publications and political groups, making democratic resistance extremely difficult. Whilst some individuals did oppose the regime, they were largely suppressed by the state and societal pressure. By the late 1930s, there was very little space left for civil society or open dissent in Germany.

On the question of public knowledge of the Holocaust, Black argues that while the Nazis did not publicly announce the Final Solution, there was widespread awareness and complicity among ordinary Germans. The disappearance of Jews, their deportation to camps, and the distribution of their property were visible and known, even if not always openly discussed. Anti-Semitic propaganda had fostered a dominant consensus, and evidence from recorded conversations of German prisoners of war reveals a lack of remorse or responsibility. Black also highlights the persecution of other groups, such as the mentally disabled, who were killed as part of the regime’s purification efforts, and the use of forced labour, which was evident in cities and factories.

In the war’s final stages, the regime’s ideology of total destruction persisted, with no willingness to negotiate surrender, and local defence forces were mobilised under Nazi control rather than the army, ensuring political passivity among the population. Black concludes that the war left Germany in a state of total devastation, a wasteland created by both the regime and the German people’s complicity, with post-war narratives often downplaying this involvement.

From 1939 to 1941, Britain, supported by its Empire, stood as the primary Allied power resisting Nazi Germany, particularly after the fall of France. The Empire provided critical resources, manpower, and strategic bases, enabling Britain to sustain its war effort despite severe financial and logistical strains. Dominions like Canada, Australia, and New Zealand contributed troops, naval forces, and airpower, while India—despite nationalist tensions—supplied a vast volunteer army that expanded significantly during the conflict. Black challenges comparisons between the British and Japanese Empires, stressing the latter's brutality and the former's role in mobilising global resistance.

The Royal Navy's protection of Atlantic convoys and the Canadian naval contribution were vital in countering German U-boats, ensuring the flow of supplies. Britain also played a key role in supplying the Soviet Union via perilous Arctic convoys and the Iran route, providing tanks, aircraft, and raw materials that bolstered Soviet resilience. Indirectly, Anglo-American air campaigns diverted German resources, easing pressure on the Eastern Front. Strategically, Churchill’s government sought to influence post-war Europe through campaigns in the Balkans and Mediterranean, though logistical constraints and Stalin's territorial advantages limited these efforts. The Anglo-American alliance under Eisenhower exemplified a complex but effective partnership, blending British experience with American resources. Black dismisses claims that earlier Western Front invasions were feasible, highlighting the impracticality of such operations before 1944.

The "Germany first" policy, he argues, was pragmatic given geographical and resource limitations in the Pacific, though Britain later redirected naval forces to support US operations against Japan. Black also addresses strained Anglo-Chinese relations, noting China's alignment with the US due to historical grievances against British imperialism.

Ultimately, Black critiques post-war narratives that overlook Britain’s sacrifices, including its financial exhaustion and imperial decline. He warns against ideological reinterpretations, such as decolonisation frameworks, obscuring the nuanced realities of Britain’s contribution. His analysis underscores the interdependence of Allied efforts, with Britain’s role as a linchpin in sustaining global resistance until broader mobilisation secured victory.

In short, the emergence of rival Germanys was shaped by both international power politics and native responses to a national crisis. Black’s lecture challenges the notion that post-war German arrangements were predetermined or simply imposed from outside, instead showing that they were contingent, complex developments arising from the interaction of external occupation policies and internal social and political dynamics.

1. Geopolitics as a Perceptual Lens

argues that geopolitics is not merely an objective analysis of geographical constraints, but fundamentally a matter of perception. Strategic understanding involves recognising how different actors interpret geographical challenges and opportunities. The Pacific theatre exemplifies this, where perceptions of distance and capability were as crucial as actual geographical realities. Not all territories are equally strategically valuable. Some seemingly important locations can be strategically irrelevant, while small islands with runway capabilities become critical. The Pacific campaign demonstrated how relatively minor territorial acquisitions could provide crucial strategic advantages. The movement of war manufacturing, establishment of new production facilities, and global supply chains reflected both geopolitical strategy and societal economic structures. The United States and Soviet Union approached this differently, with each adapting industrial capabilities to geographical and strategic requirements.

2. Technological Transformation of Geographical Constraints

A central argument is how technology fundamentally altered traditional geographical limitations. For instance, air power dramatically changed strategic calculations, with relatively modest aircraft operations like the Pearl Harbor attack reshaping power dynamics. The ability to cross previously insurmountable geographical barriers became increasingly possible through technological innovation.

3. Strategic Complexity Beyond Pure Geographical Determinism

Whilst geography provides fundamental parameters, Black emphasises that strategic decision-making involves multiple complex factors. Geographical constraints are not absolute determinants but interact with technological capabilities, political considerations, and strategic perceptions. Strategic decisions were not purely rational. Imperial considerations, national prestige, and psychological factors played significant roles. The British desire to recapture Singapore, for example, was as much about maintaining imperial image as pure military strategy.

Black suggests geopolitics should not be seen as a deterministic field but as an interactive, multifaceted analytical approach. Strategic decisions emerge from complex interactions between geographical constraints, technological capabilities, political objectives, and human perceptions. The atomic bombing of Japan represents the ultimate demonstration of overcoming geographical constraints, fundamentally altering strategic paradigms by transcending traditional spatial and temporal limitations. Thus Black argues that geopolitics is best understood as one useful analytical lens among many, providing insights into strategic thinking without claiming absolute explanatory power. It requires a nuanced, multidimensional approach that recognises the complexity of human strategic behaviour.

Black highlights the role of geography in shaping geopolitical strategies, noting that sometimes geographical considerations trumped ideological ones. For example, British concerns about China in 1944 were not about Chinese communists but about the Chinese Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek. He also discusses the influence of geopolitical theories, such as Nicholas Spykman's rimland thesis, which emphasised the importance of maritime power alongside continental alliances to prevent the dominance of Eurasia. He argues that the end of World War Two saw a different situation compared to the end of World War One. The United States maintained a firm commitment to both Europe and East Asia, leading to the establishment of NATO and participation in the Korean War. The rise of an authoritarian communist government in China by 1949 added a new dimension to the geopolitical landscape, making China not just a support to the Soviet Union but an active and dangerous player in its own right.

Black questions the role of the United Nations in trumping geopolitical considerations, suggesting that it could produce commitments for America to engage in countries where there seemed to be no real imperative. He argues that ideological reasons for grave distrust or dislike are often underplayed in discussions of geopolitics. The dynamic characteristics of China and the Soviet Union, particularly after the Communist takeover in China in 1949, left analysts struggling to keep up.

He further emphasises that geopolitics was a field of debate rather than a clear-cut prescription. He points out that American policy during the Cold War involved a series of choices, and the visualisation of the world through different cartographic projections could create different impressions of global power dynamics. He also discusses the British perspective on the Soviet Union, noting that some British diplomats saw the striving for security of a state with no natural frontiers as a central ideology, rather than communism.

The professor concludes by discussing the dualist perspective of geopolitical strategists from major participating countries like the United States and Britain, whose analysis is inevitably tied up with a sense of national interest, and those from neutral countries or countries with less at stake, who may have a different perspective. He suggests that this dynamic is still relevant in the present day, particularly in the context of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and the geopolitical strategies of various nations.

1. Projection and Perception

Black highlights how even cartographic projections reflected geopolitical perspectives. American maps centered on the United States, psychologically reinforcing its global centrality, while British maps traditionally used the Greenwich Meridian.

2. Security Motivations

Drawing on a British diplomatic report from 1947, Black suggests that national security concerns often transcend ideological narratives. The Soviet Union's actions were fundamentally driven by a historical quest for security rather than purely communist ideology.

1. Contextualising the 1960s: Black stresses that while the 1960s saw developments with long-term implications, such as the Sino-Soviet split, contemporaries did not have the benefit of hindsight. Their decisions were influenced by the immediate Cold War context, including the domino theory and the legacy of World War II.

2. The Domino Theory: This theory, popularised by President Eisenhower in 1954, was more of an image than a rigid theory. It suggested that the fall of one country to communism would lead to the collapse of others in the region. Black notes its application in justifying interventions, such as in Cuba (Bay of Pigs) and Southeast Asia, but also its limitations and fallacies, particularly in overestimating the linear spread of communism.

3. Cold War Interventions: The U.S. intervened in various regions, including the Middle East (e.g., Jordan in 1957, Lebanon in 1958) and Southeast Asia, to prevent the spread of Soviet influence. These interventions were often responses to specific crises and aimed to shore up pro-Western governments, reflecting the broader strategy of containment.

4. The Vietnam War: Black argues that the Vietnam War was a complex geopolitical conflict, influenced by both physical and human geography. He highlights the mismatch between U.S. and North Vietnamese strategies, the role of airpower, and the challenges of fighting an insurgency. The war also demonstrated the limitations of applying geopolitical theories in practice, as it became a proxy conflict with global implications.

5. Sino-Soviet Split: This split reshaped global geopolitics, introducing new dynamics within the communist bloc. Black notes that while the split weakened the monolithic communist threat, it also created opportunities for rivalry between China and the Soviet Union, complicating Cold War strategies.

6. Indonesia and Southeast Asia: The 1965 military coup in Indonesia, supported by the West, was a significant geopolitical event. Black contrasts its strategic importance with the Vietnam War, suggesting that Indonesia’s shift had more profound regional implications. This highlights the difficulty of prioritising conflicts in a multipolar world.

7. Geopolitical Flexibility and Prioritisation: Black emphasises the flexibility of geopolitical strategies and the challenges of prioritisation. He draws parallels between the Cold War era and contemporary issues, such as the U.S. balancing its focus between Ukraine and Taiwan. This underscores the ongoing difficulty of applying rigid models to dynamic international relations.

8. The Role of Ideology and Psychology: Black critiques the notion of international relations as a rigid science, arguing that ideological factors and psychological elements (e.g., morale, prestige) play significant roles. He highlights how attitudes and perceptions influenced decision-making during the Vietnam War and other conflicts.

9. Modern Relevance: Black concludes by drawing lessons from the 1960s for contemporary geopolitics. He notes the recurring challenges of prioritisation, the complexities of proxy conflicts, and the limitations of theoretical models in predicting outcomes. He also highlights the importance of understanding historical context to avoid oversimplifying current issues.

1. Origins of the IRA:

The IRA’s roots lie in long-standing divisions within Irish nationalism, exacerbated by the Civil War (1922–1923). The Provisional IRA (formed in 1969) emerged as a more militant faction, advocating for Irish reunification through force. Black describes it as a “classic attempt to apply revolutionary warfare theories,” aiming to provoke British forces to such an extent that the state would collapse, allowing a socialist republic to take over. The Provisional IRA’s strategy included targeting British security forces, establishing “no-go areas” in Belfast and Derry, and using terrorism to destabilise the region.

2. British Military Deployment:

British troops were initially sent to Northern Ireland in 1969 to maintain order, akin to the US federal response to civil rights protests. However, as violence escalated, the military shifted from a counter-insurgency strategy to one focused on countering terrorism. Operations like Operation Motorman (1972) aimed to reclaim territory from the IRA but faced challenges due to the guerrilla tactics and civilian presence. The British Army’s role was described as primarily defensive, aiming to “hold the line” until political solutions could be negotiated.

3. Challenges and Strategies:

- IRA Tactics: The Provisional IRA relied on bombings, assassinations, and border smuggling (e.g., weapons via the Irish Republic). Funding came from criminal activities (drug trafficking, extortion), Soviet bloc support, and Irish American sympathisers.

- British Response: Intelligence gathering and infiltration (e.g., informants within the IRA) were effective but insufficient. The government avoided decisive military action in the Republic, critiqued as a failure to disrupt the IRA’s infrastructure.

- Public Perception: Most Catholics did not support the IRA, but the movement’s portrayal as defenders of the community fuelled tensions. British troops were occasionally accused of brutality, though Prof. Black emphasises they operated professionally under difficult conditions.

4. Political and External Factors:

- The Good Friday Agreement (1998) eventually brought a political resolution, but the conflict left deep societal scars.

- External support for the IRA waned after the Cold War, removing financial and logistical resources.

- Comparisons to other conflicts (e.g., Algeria, Kenya) highlight similarities in insurgent tactics but note the IRA’s limited military effectiveness compared to groups like the French Foreign Legion.

5. Legacy:

The Troubles demonstrated the complexity of counterterrorism. While the British Army managed to contain violence, the political process was crucial. Prof. Black critiques the lack of a robust strategy to dismantle the IRA in the Republic and underscores the long-term social and political divisions. The lecture concludes by reflecting on the military’s professionalism and the eventual shift toward political reconciliation.

Professor Black argues the Falklands War was a significant, and perhaps surprisingly successful, British victory given the prevailing defence policies and geopolitical context of the time. He challenges simplistic narratives and delves into the complexities surrounding the conflict.

Defence Policy Shift: Since the 1960s, British defence policy had been shifting away from a focus on naval power and towards NATO commitments and areas further afield. This meant a weakening of the navy’s capacity for distant water operations, a trend not unique to the Thatcher government.

Argentinian Intentions: Black questions whether the perceived threat from Argentina was a genuine assessment of their intentions, or a misreading influenced by intelligence failures – drawing parallels to intelligence failures in 1941 and the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. He highlights the “noise” inherent in intelligence gathering.