This Extended Essay from an outstanding former student received an 'A' from the IBO in 2023.

Extended Essay

IB Subject: History

The Death of King Ludwig II. of Bavaria

Research Question: Was King Ludwig II. of Bavaria’s death suicide, murder or misadventure?

Word count: 4000

“I wish to remain an eternal enigma to myself and others.” — King Ludwig II. of Bavaria2

Note:

The definition of “insane” used in von Gudden’s psychological examination of Ludwig declaring him as such is now neither scientifically nor socially accepted. For example, reports of homosexual tendencies and affairs were cited as “evidence” for sexual deviance and unsoundness of mind within the report. The use of the term within this essay therefore refers exclusively to the obsolete 19th-century evaluation of mental state.

Introduction

In the 21st century, the public perception of King Ludwig II. of Bavaria is that of an eccentric fairy king, desperately eluding reality in his lonely dream-world. A strong public interest in his life and legacy remains and he has become a symbol for magic and mystery.3 Indeed, depictions of Ludwig grace t-shirts, beer mugs, and snow globes. His “fairy-tale” castles, especially Neuschwanstein, the world famous piece of 19th-century Historicist architecture, attract millions of tourists annually and can even be found in Legoland and Disney World.4 Upon further examination of Ludwig’s life, however, it becomes clear that the romanticization and commercialization of his castles and extravagant lifestyle has led to a misrepresentation of his character and a trivialization of his death.

On June 8, 1886, Ludwig’s personal physician, Dr. Bernhard von Gudden, published a report proclaiming his alleged “insanity”, following which he was removed from office, arrested and relocated to Schloss Berg [Castle Berg].5 At around 18:35 on June 13, 1886, Ludwig and von Gudden went for a walk along Starnberger See [Lake Starnberg].6 When the two were not back by 20:00, psychologist Dr. Franz Carl Müller, anxious that something may have happened to them, organized a search involving the entire castle staff within half an hour.7 Between 23:00 and midnight, two lifeless bodies were found floating in Lake Starnberg, and were quickly identified as those of Ludwig and von Gudden.8

While the bodies were identified, the cause of their deaths was not, and questions have remained ever since (see Appendix XI). This tragedy would result in arguably one of the most famous mysteries in Bavarian history and lead to the question investigated in this essay which to this day has yet to be answered:

Was King Ludwig II. of Bavaria’s death suicide, murder or misadventure?

The plausible theories on Ludwig’s cause of death can be broadly categorized into suicide, murder and misadventure. Considering the death involving the former Bavarian Head of State remains unsolved, the question must be continually reexamined until satisfactory explanations have been found for all the evidence found in the case. There are two implications of what the reality of the events on June 13, 1886 was. Should Ludwig have drowned accidentally, this is nothing more and nothing less than a tragedy. If however, Ludwig was either murdered or driven to suicide by political circumstances following his deposition, which CDU politician and lawyer Peter Gauweiler argues would incriminate the state by making it indirectly responsible for the death of the victim, this “state crime” would reflect the conditions of the government as well as the extent to which it was willing to go to accomplish its interests.9 As confided by Prof. Dr. Hermann Rumschöttel, the former Head of the Bavarian State Archives, Ludwig’s era must be judged within the historical context of his time (see Appendix I).10 As today’s societal standards have changed, evidence will be evaluated based on 19th-century norms.

The difficulty with this question is that because the few documents that do exist are ambiguous, dubious or destroyed, much depends on eyewitness testimonies which contradict each other in nearly every aspect of the case. The overabundance of unreliable statements in addition to the lack of clarity concerning what actually happened are most likely the reasons for the surplus of theories. To paraphrase a comparison stumbled upon during the course of this investigation, there are probably more theories as to how Ludwig died than bricks used to build Castle Neuschwanstein; some even count 26.11 The wide variety of sources included personal correspondence with experts such as Dr. Eisenmenger, a coroner and professor at Ludwig-Maximilian-University Munich, and researcher Peter Glowasz, who even offered a telephone interview (see Appendices II and X), both of whose insight proved to be critical to the investigation. Lake Starnberg itself was also a highly valuable source, as it not only made the situation the bodies were found in easier to imagine, but also illuminated the remaining reluctance of the royal family, the Wittelsbacher’s, to involve the public.

Section I: Dismembered Mind

The first challenge which immediately presents itself when examining this question is that no official cause of death can be discerned from the autopsy report. The only official document faintly hinting at a cause of death is an extract from the death records of the Parish in Aufkirchen near Starnberg, revealed by the Archive of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising, which lists that Ludwig “plunged himself into the lake in his mental disturbance” (see Appendix VIII).12 Indeed, despite the lack of clarity in the autopsy report, the official narrative tends to support a view of suicide.

Ludwig had suffered some serious blows of fate by the time he died. His father having passed away unexpectedly in 1864 when he was 18, Ludwig suddenly had the massive responsibility of the throne thrust upon him.13 In 1870, the peaceful and young King was contractually obligated to support the war effort of Prussia against France.14 Following the unification of Germany after victory in 1871, the Kaiser now ranked higher than the Bavarian King, a development which deeply appalled the Wittelsbacher family.15 Ludwig complained he was now the “shadow of a monarch”, and his overall mental condition was to decline from then onwards, abandoning even personal hygiene by the end of his life.16 While this background by no means proves that he committed suicide, it does provide support for the long-term depression he is said to have developed, also in part outlined in von Gudden’s report.

Ludwig’s arrest and removal from office also immensely affected his psychological condition; according to the contemporary journalist Anton Memminger, whose priority may have been writing a sensationalistic piece and selling copies rather than finding the truth, nevertheless quotes Ludwig as having said that he “would have been able to bear” being refused his crown, but not being “denied [his] sanity, [his] freedom taken and being treated like [his] brother Otto”, who had been declared “insane” and incarcerated at Schloss Fürstenried [Castle Furstenried] in 1883.17 The fact that this view emerged following Ludwig’s death shows that it has historical relevance. Furthermore, psychiatrist Professor Dr. Heinz Häfner, although not an historian, nevertheless outlines the almost religious significance Ludwig’s castles, which irredeemably buried him in debt, had in his life. Häfner describes Ludwig’s excessive building as a psychiatric phenomenon now known as a non-substance addiction, commonly associated with gambling, and argues that it was not only his “main joy in life”, but that building and living were synonymous in his mind.18 This is supported by Ludwig himself, who stated in January 1886 that if his castles were confiscated, he would “either immediately kill [himself] or leave the accursed land.”19 Furthermore, a number of staff eyewitness accounts, although recorded after his death under little known circumstances, do support this argument, recounting Ludwig’s suicidal ravings; he is said to have requested poison, cyanide, a kitchen knife and keys to the castle’s highest tower in his three final days.20 One even claimed Ludwig had romanticized a “death in the water” by describing it as “beautiful”.21 Rumschöttel argues that the “deeply wounded” King recognized the “hopeless, grievous, degrading and humiliating” situation he was in and, strangling the doctor trying to stop him, entered Lake Starnberg without the intention of leaving it.22

However, there are several aspects of Ludwig’s life which strongly contradict the theory of suicide. Ludwig has often been described as a strong swimmer.23 He also spent large parts of his childhood and adolescence in Berg and knew the area well; if the intention of suicide had existed, he would neither have chosen an area where the water was so shallow, nor removed his two bulky overcoats before entering the lake.24 Moreover, Ludwig was a devoted Catholic who had practiced his religion all his life; vast extracts of his diaries see him constantly attempting to “redeem himself” for his homoerotic passions, which he regarded as sinful and immoral.25 This highlights that his religious understanding was entrenched deeper in his understanding than his natural disposition. Knowing this religious background, Ludwig would have regarded suicide as the ultimate mortal sin and it is highly unlikely he would have taken this step. Moreover, although Ludwig’s suicidal statements appear to be signs of a genuine death wish, making a note of his tone is critical to avoid misinterpretation. When compared to letters of other German aristocrats at the time, Ludwig’s often come across as melodramatic.26 While this was certainly a part of his eccentric personality, he tried to gain financial advantages from this behavior.27 Though largely unsuccessfully, a pattern exists of Ludwig threatening suicide to persuade national and international government officials, dubious creditors and fellow aristocrats to provide him with the necessary funds to fuel the upkeep of his flamboyant lifestyle and architectural pursuits.28 For example, there is a particularly outraged letter of Ludwig’s bitterly berating the Bavarian Landtag [parliament] for not granting him this support.29 This seriously diminishes the credibility of these remarks when taken at face value.

Some insight can be gathered by evaluating whether Ludwig was truly “insane”. Concerns have been raised by coroners, doctors and psychiatrists alike over the extensive descriptions of Ludwig’s brain in the autopsy. According to Dr. Eisenmenger, this level of detail was uncommon, and he supposes it was intended to prove Ludwig’s “insanity”.30 This portrays that the main focus of the autopsy was rather on sustaining the official version than determining a cause of death. His “mental disarray” thus allowed the official narrative to be maintained and provided justification for Ludwig’s burial in the Wittelsbacher tomb in St. Michael’s Church in Munich (see Appendix IX); the same was the case of Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary’s suicide in 1880, whose funeral still included all Catholic ceremonies.31 Regarding the “insanity” report itself, Dr. Häfner argues that it is “ethically, professionally and scientifically unacceptable”.32 The issues with the source do not end there: some of the eyewitnesses who testified about Ludwig’s final days had also been questioned in the “insanity” report, for which they were repeatedly brought in and pressured to make statements incriminating the King.33 This indicates that von Gudden’s associates were already accustomed to manipulating eyewitness statements; seeing as three of the doctors present at the autopsy were also involved in the “insanity” report, there would have been little hesitation in employing similar methods shortly thereafter.34 As the only official source presenting a diagnosis of depression, the report’s limitations far outweigh its value and the information cannot be trusted. The secretive nature of the situation at Berg is furthered by an oath on the Bible the 15 official eyewitnesses of the crime scene were forced to take, entailing that they were never to speak of anything they had seen that night.35 Many of those who kept this promise were later rewarded; an official statement as to why this was undertaken has to this day not been provided.36 These mysterious and inexplicable circumstances provide a transition into the rapidly spreading conspiracy theory that the King was murdered.

Section II: Conspiracy

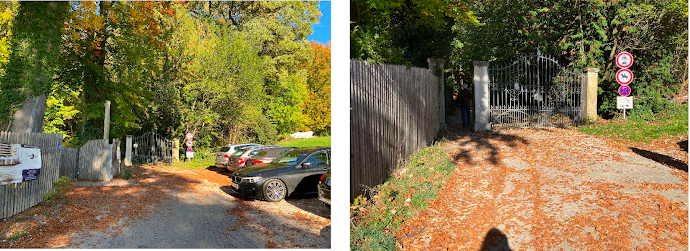

One of the reasons so much attention is still paid to this case is that so much of it remains secretive. When attempting to gain a better view at the physical site by crossing into a fenced-off area, one is rapidly met by a security boat, indicating the installation of motion sensors and that inquiries are undesired. Only by walking through dense natural territory on a slope is one able to access the banks. It also becomes clear that the cross displayed in the lake marks the area where the bodies were found — the actual place of death is believed to be approximately 50 meters further south-west based on tracks discovered at the lake’s ground.37 Additionally, while the opening of the high hedges did exist in 1886, it was not at the cross, as it is now, but also south-west, where Ludwig’s hat, overcoats and footprints were found (see Appendices V and VI).38 By being tantalizingly close to what it once was but not quite, the reconstruction of the site is inherently misleading and historically inaccurate; this immediately creates an issue for an historian, as the evidence can no longer be regarded in its correct form.

Self-proclaimed Ludwig researcher Peter Glowasz holds the opinion that if the casket were to be opened, one would find Ludwig’s embalmed body with two bullet holes in the back.39 Glowasz argues that Ludwig was shot by two Gendarmes when trying to escape. Examples Glowasz often refers to include the testimonies of fisherman Lidl, who was on the boat which recovered the bodies and claims to have seen bullet wounds upon the King’s body.40 The hut in which Lidl claims the blood-soaked corpses were cleaned was torn down a few days after the incident.41 In personal communications, a point Glowasz refers to multiple times is that Dr. Rudolf Magg of the Starnberg Court Commission, the doctor responsible for ascertaining the preliminary cause of death, later confessed on his deathbed that he had falsified the accounts; in reality, he had seen bullet wounds.42 According to Glowasz, this account outweighs all counterarguments.43 This information clearly supports the theory of murder.

A further theory is planned assassination, strengthened by the fact that there were certainly parties who would have profited from the King being gone and had the means to stage a large-scale cover-up. As Head of State of a constitutional monarchy, Ludwig was able to appoint and dismiss the ministers comprising the Bavarian executive whenever he pleased; this he abused, describing the continual denials for financial support as “withholding loyalty” and threatening to dismiss the ministers if they continued refusing to comply.44 On the day of his death, Ludwig stated that “they” would forever need to keep him in captivity, as they would otherwise “always have to fear [his] revenge”.45 This was not limited to politicians, even Ludwig’s relatives, especially the soon-to-be Prince Regent Luitpold and his sons, would have been made responsible for paying the King’s debts should he prove unable to do so, a sum which had reached approximately 20 million Marks by 1886.46 While this information certainly is not evidence for either party’s involvement, it shows that there was a personal motivation each may have had for “getting rid” of Ludwig.

Deconstructing the evidence, however, accentuates the issues with both theories. Historian Oliver Hilmes writes that Glowasz’s theory is not supported by believable evidence, as it most often comprises, “someone who heard from someone that a third person has a deceased aunt, who heard from her great uncle on his deathbed, that...” and so forth.47 While this is an exaggeration, Dr. Magg’s allegedly monumental deathbed confession is provided by a fourth-hand source and earlier versions of the information cannot be found, thus significantly decreasing its reliability.48 It must also be noted that the “gunshot version” was Lidl’s third “recollection” of the events, following suicidal and accidental drowning; as these testimonies vary so radically, Lidl cannot possibly be regarded as a credible witness.49 This theory is based solely on the premise that all official documents, most of all the autopsy report, were faked; seeing as the autopsy was conducted in the presence of no less than thirteen doctors, this is extremely unlikely.50 Former Senior Chief Prosecutor Wilhelm Wöbking describes the assumption that, disregarding the group sworn to secrecy, the multitude of doctors, consultants and public onlookers present in the area could have been silenced as “grotesque”.51 Had the revered Head of State truly been shot, it seems impossible that these statements of dubious origins would be among the most compelling accounts, especially as the mandatory oath did not even include all the anonymous onlookers that came and left throughout the night. As silencers were not invented until the early 20th century, Wöbking notes that gunshots would certainly have been heard from the castle displaced by merely 800 meters.52 Perhaps not possessing an explanation, Glowasz dodged this question.53 From a criminalistic standpoint, Wöbking classifies the entire murder hypothesis as “completely untenable” and “abstruse speculation”.54 Therefore, due to the lack of evidence, Glowasz’s argument that Ludwig was shot is highly implausible.

Additionally, although anxiety in the Wittelsbacher family and amongst politicians was an unofficial reason for their support of the deposition, it is crucial to differentiate; while there were clear reasons why his disenfranchisement would have been welcomed by both his family and the political scene, this issue was “resolved” by his removal from office.55 Being stripped of his power, Ludwig was no longer a danger to them. There is no discernible reason why those with the means to stage a cover-up would have wanted to murder the King. As no substantial incriminating evidence can be found, the theory of a planned assassination by either party can be set aside.

Section III: Nothing More Yet Nothing Less Than a Tragedy

Having dismissed suicide and murder as causes of death, this leaves a third option: misadventure. Although no cause of death is listed in the autopsy, what can be inferred from the medical information provided supports the conclusion of sudden drowning. Typically, the blood found in an autopsy is clotted.56 The blood in Ludwig’s skull, however, was “dark, fluid and unclotted”; this is a sign for a sudden death such as drowning as it means that the subject in question died before the coagulation process set in.57 Other classic signs of drowning include watery contents found in the stomach, anemic spleen, and bloated face, all of which were noted in Ludwig’s autopsy.58

Furthermore, although the scant description of the lungs include no mention of water found within, leading many to assume Ludwig was murdered, this does not necessarily mean he did not drown. Some illumination was offered by Dr. Eisenmenger in personal correspondence, who cited a phenomenon known as ‘dry drowning’ as a possible justification for this ostensible inconsistency (see Appendix II).59 Approximately 12-20% of all drowning victims ‘dry drown’, in which patients suffer asphyxiation rather than water aspiration, meaning that no water enters their lungs and thus cannot be detected in an autopsy.60 This medical phenomenon is crucial in the case as it offers a reasonable explanation for Ludwig to have drowned. For the lack of hyperinflated lungs in the autopsy typical of dry drowning victims, Dr. Eisenmenger outlines how extensive resuscitation attempts can blur the forensic appearance of lungs.61 With this information, sudden drowning is the most logical cause of death which can be derived from the medical findings in the autopsy. No autopsy was conducted for von Gudden on his family’s wishes, but conspicuous choke marks on his neck described by a number of eyewitnesses corroborate the presumed narrative of a struggle from which Ludwig, at least fleetingly, emerged victorious.

With this in mind, there are several plausible medical complications which could have caused Ludwig to drown. Although a good swimmer in young years, this had likely declined by 1886 due to his obesity — the autopsy report notes his abdominal girth as 120cm.62 This overweight in addition to the temperature shock of 12 ̊C cold water must have impeded and exhausted Ludwig in the ensuing struggle.63 Eyewitnesses also state that the King’s last meal was abundant in both food and alcohol intake; though unclear how typical this conduct was for Ludwig, he entered the water on a full stomach and under the influence of alcohol, which would have weighed him down and limited his ability to act.64 On the subject of substances, though evidence to prove drug abuse is insufficient, it is beyond doubt that Ludwig was taking various drugs and medication without medical supervision.65 Having been deprived of many privileges with his arrest, it is possible that Ludwig was suffering physical symptoms of withdrawal at his time of death, which would have further weakened him. Additionally, Dr. Hubrich, a signatory of both the “insanity” and autopsy reports, stated in an interview that the wet tuff sand on the seabed would have been difficult to extract oneself from, especially under exhaustion.66 In any case, as Ludwig was an overweight man in 12 ̊C cold water engaging in a physical struggle, not to mention under extraordinary psychological circumstances, it is more than conceivable he could have lost consciousness and drowned.

But all this considered, why did Ludwig even enter the water in the first place? The most likely scenario is that he had intended to escape the forlorn life he was unjustly sentenced to through Lake Starnberg and died in the midst of this pursuit. After a supervised walk with von Gudden at about 11:00 along what was to become a crime scene twelve hours later, Ludwig had stated that he wanted to return to this area in the evening without “unnecessary” guards, and von Gudden agreed.67 This is crucial to note as Ludwig may have come up with a spontaneous escape plan during the first walk and decided to carry it out on the unsupervised return. Knowing the area like the back of his hand, Ludwig would have been aware that the border of the castle’s park to the port of the nearby village Leoni was about 350 meters away from where he is believed to have entered the water, enclosed by a protruding metal grating.68 Regarding the site, this distance is not as far as it appears to be on a map, and a decent swimmer could easily make this distance. Perhaps Ludwig made this calculation, too, and overestimated his physical condition. When comparing the site with the direction of Ludwig’s steps in eyewitnesses’ sketches, this is precisely the direction he was headed towards (see Appendix III and IV).69 While not entirely accurate due to bad weather conditions and search-party induced crime scene disruptions, various eyewitness statements roughly outline the same appearance of the steps.70 Dr. Hubrich is convinced that while trying to swim to freedom along the shore, Ludwig must have been held up by von Gudden, who attempted to prevent the King’s escape, leading to a struggle which killed both.71 Multiple eyewitnesses have indicated that, although there was a storm, boats had allegedly been passing the banks all evening and a carriage was seen waiting before the southernmost gate of the park (see Appendix VII).72 Whilst the merit of these statements is uncertain, they suggest that there may indeed have been a secret escape plot in place for the King — this is not completely out of the blue, seeing as many of those amongst the Bavarian public adored their King and the deposition left them shocked, confused and outraged. In any case, whether an external escape plot was in place or Ludwig simply seized the opportunity before him, an escape attempt is by far the most logical explanation for his entrance into the lake. Therefore, using the available evidence, the theory that Ludwig drowned accidentally in the pursuit of freedom is the most reasonable.

Conclusion

To conclude, it is most likely that Ludwig died by misadventure through accidental drowning in a failed escape attempt. Whilst he probably suffered the consequences of long lasting loneliness and various mental health disorders, the “investigation” conducted in von Gudden’s “insanity” report was unethical and unscientific and intended to remove the King from the throne. He was an eccentric, distanced and complicated character, traits which were manipulated into proof of “insanity”. If Ludwig had truly been shot, it would have been near impossible to keep this a secret with all the people who were present at the crime scene. It is as Hilmes states: one cannot base a murder case solely on third- or fourth- hand eyewitness statements as Glowasz does. One aspect is fairly certain: Ludwig recognized that he could no longer stand his current situation, which left him with the options of suicide and escape. Ludwig’s suicidal threats have not been interpreted within their context, as he was often melodramatic and promised himself benefits from these statements. While it is possible Ludwig committed suicide, it is more likely he planned to escape and did not succeed. Having eliminated the threat of his doctor attempting to hold him back, Ludwig likely experienced an exhaustion-related medical issue which rendered his return to shore impossible, leading him to dry-drown in Lake Starnberg. In the words of Rumschöttel, though, no one can seriously claim that they are able to explain Ludwig’s death with complete certainty.73 Many uncertainties about the circumstances of King Ludwig II. of Bavaria’s death — and life — will remain forever. Thus he will, just as he wished, remain an “eternal enigma to [himself] and others.”

FOOTNOTES

4 Peter O. Krückmann, Das Land Ludwigs II.: Königsschlösser und Stiftsresidenzen in Oberbayern und Schwaben (Munich: Prestel, 2000), 24; Hermann Rumschöttel, Ludwig II. von Bayern (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2011), 88

5 Hermann Rumschöttel, Ludwig II. von Bayern (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2011), 121 [translation mine]

6 Christopher McIntosh, Ludwig II of Bavaria: The Swan King (London: Barnes & Noble, 1997), 196

8 McIntosh, Ludwig II. of Bavaria, 197

9 Peter Gauweiler, “Bernhard von Gudden und die Entmündigung und Internierung König Ludwig des Zweiten aus juristischer Sicht.”, in Bernhard von Gudden, ed. Hans Hippius and Reinhard Steinberg (Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 2007), 93-107

11 Alfons Schweiggert und Erich Adami, Ludwig II.: Die letzten Tage des Königs von Bayern (Munich: München Verlag, 2014), 32117 ibid., 361; Schweiggert and Adami, Ludwig II., 79 [translation mine]

18 Heinz Häfner, Ein König wird beseitigt: Ludwig II. von Bayern (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2011), 177, 182-183 [translation mine]

19 Hacker, Ludwig II. von Bayern, 319 [translation mine]

12 Email to author, 25 Mar. 2022 (see Appendix VIII) [translation mine]

13 Oliver Hilmes, Ludwig II.: Der unzeitgemäße König (Munich: Random House, 2018), 73

14 Rumschöttel, Ludwig II. von Bayern, 59

15 Peter Wolf, Richard Loibl and Evamaria Brockhoff, Götterdämmerung: König Ludwig II. und seine Zeit (Augsburg: Primus Verlag, 2011), 75; Hilmes, Ludwig II., 195

16 Werner Richter, Ludwig II. - König von Bayern (Munich: Bruckmann, 1996), 112-13; Rupert Hacker, Ludwig II. von Bayern in Augenzeugenberichten (Düsseldorf: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1980), 185 [translation mine]

18 Heinz Häfner, Ein König wird beseitigt: Ludwig II. von Bayern (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2011), 177, 182-183 [translation mine]

19 Hacker, Ludwig II. von Bayern, 319 [translation mine]

21 ibid. [translation mine]

22 “Ludwig II. – Theorien und Ansichten.”, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 9 Jun. 2017,

www.sueddeutsche.de/muenchen/wolfratshausen/ludwig-ii-theorien-und-ansichten-1.3540636

24 Wöbking, Der Tod des König Ludwigs II., 151, 265, 271

27 McIntosh, Ludwig II. of Bavaria, 179

28 Schweiggert and Adami, Ludwig II., 14-15

29 Häfner, Ein König wird beseitigt, 176, 484

30 Wolfgang Eisenmenger, email to author, 9 Nov. 2022 (see Appendix II)

Note: The ability to diagnose psychological disorders in post-mortem brain examinations has since been found to be impossible.

31 ibid. (see Appendix II)

34 ibid., 306-318, 372-376

35 Schweiggert und Adami, Ludwig II., 211

36 ibid.

38 Schweiggert und Adami, Ludwig II., 189

39 Peter Glowasz, telephone conversation with author, November 14, 2022 40 Hilmes, Ludwig II., 383 [translation mine]

42 Peter Glowasz, telephone conversation with author, November 14, 2022

43 ibid.

44 Wöbking, Der Tod König Ludwigs II., 293

45 Richter, Ludwig II., 315; Häfner, Ein König wird beseitigt, 13, 178, 180, 231

46 ibid. Note: as of November 5, 2022, this sum (20 million Marks) would be worth around €134,600,000

48 Schweiggert und Adami, Ludwig II., 182

49 Hilmes, Ludwig II., 383

50 Wöbking, Der Tod des König Ludwigs II., 373

51 ibid., 272; Hilmes, Ludwig II., 384 [translation mine]

53 Peter Glowasz, telephone conversation with author, November 14, 2022

54 Wöbking, Der Tod des Ludwig II., 272-273; Hilmes, Ludwig II., 384. [translation mine]

57 Wöbking, Der Tod des König Ludwigs II., 224, 374 [translation mine]

58 ibid., 226-228. [translation mine]

59 Wolfgang Eisenmenger, email to author, 12 Mar. 2022

60 Mark Harries, “Drowning And Near Drowning,” British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) 293, no. 6539 (1986): 123. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29523838

62 Hilmes, Ludwig II., 386; Wöbking, Der Tod des König Ludwigs II., 373

63 ibid.

64 Hacker, Ludwig II. von Bayern, 388; Wöbking, Der Tod des König Ludwigs II., 378 [translation mine]

67 Hilmes, Ludwig II., 376 [translation mine]

68 Richter, Ludwig II., 317; Hacker, Ludwig II. von Bayern, 406

71 von Liebermann, “Abnorm, aber nicht geisteskrank,” 2537; ibid. 167-177

72 Schweiggert and Adami, Ludwig II., 164-165; Hacker, Ludwig II. von Bayern, 393

Appendix I:

Email communications with historian and former Head of the Bavarian State Archives Prof. Dr. Hermann Rumschöttel on October 21st, 2021

Appendix II:

Email communications with coroner Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Eisenmenger of Ludwig-Maximilian- University Munich on March 21st, 2021 and November 9th, 2022

Appendix III:

Original situation plans of tracks found on the ground of Starnberger See created on June 15th, 1886 by district construction engineer Franz Xaver Haertinger on behalf of the district of Munich.

Appendix IV:

Situation plan of the crime scene created by two university students at around 07:00 on June 14th, 1886 during unclear weather conditions

Appendix V:

A sideways view of the place the bodies were found, shown by the large wooden cross in the background, and the location where Ludwig entered the water, marked by a cross of dried branches laid by well-informed passersby (author’s images, 16 Oct. 2022)

Appendix VI:

Votive Chapel Starnberg dedicated to Ludwig II., built by Prince-Regent Luitpold in June 1896, a decade after the tragedy, and the view to the site (my own photos to replace those identifying student).

Appendix VII:

End of Castle Berg’s park, approximately 350 meters from the road, which is on a downward slope and leads straight to Leoni. 74 (author’s images, 16 Oct. 2022, see Page 18)

Appendix VIII:

Personal correspondence with the Archive of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising and an excerpt from the official death records of the Parish in Aufkirchen near Starnberg. Ludwig is the fifth down, written in blue ink

Appendix IX:

Ludwig and his brother Otto’s caskets in the Wittelsbacher tomb in St. Michael’s Church, Munich (author’s images, 5 Nov. 2022)

Appendix X:

Ludwig’s death makes headlines to this day; here the edition from July 13th, 2022, reading: “The Search for Clues on his Date of Death: Ludwigs Last Secret” (author’s image, 13 Jul. 2022)