Augusta Vindelicorum had been founded in

15 BCE by Drusus and Tiberius on the orders of their stepfather, the

emperor Augustus. The name means "Augusta of the Vindelici". This

garrison camp became the capital of the Roman province of Raetia by

roughly 120 CE, enjoying growth as part of its four hundred year

affiliation with the Roman Empire and due to its excellent military,

economic and geographic position at the convergence of the Alpine rivers

Lech and Wertach, and with direct access to most important Alpine

passes. Thus, Augsburg was the intersection of many important European

east-west and north-south connections, which later evolved as major

trade routes of the Middle Ages. Augsburg was sacked by the Huns in the

5th century, by Charlemagne in the 8th century, by Welf of Bavaria in

the 11th century, and by Anglo-American retribution in the 20th century;

arising each time to greater prosperity.

Augusta Vindelicorum had been founded in

15 BCE by Drusus and Tiberius on the orders of their stepfather, the

emperor Augustus. The name means "Augusta of the Vindelici". This

garrison camp became the capital of the Roman province of Raetia by

roughly 120 CE, enjoying growth as part of its four hundred year

affiliation with the Roman Empire and due to its excellent military,

economic and geographic position at the convergence of the Alpine rivers

Lech and Wertach, and with direct access to most important Alpine

passes. Thus, Augsburg was the intersection of many important European

east-west and north-south connections, which later evolved as major

trade routes of the Middle Ages. Augsburg was sacked by the Huns in the

5th century, by Charlemagne in the 8th century, by Welf of Bavaria in

the 11th century, and by Anglo-American retribution in the 20th century;

arising each time to greater prosperity. Hitler first visited Augsburg in March 1920 through contact with his patron Gottfried Grandel who, on March 13, 1920, also organised his flight from Augsburg to Berlin. In Augsburg, the Nazis commemorated October 27, 1922 as the founding date of their local party and celebrated the site of its founding at the Cafe Pelikan in the Jakobervorstadt. On January 12, 1921, Hitler gave a speech in Augsburg on the subject of "The Worker in the Germany of the Future" at the Café Mamimilian. A second speech by Hitler in the same café followed on May 10, 1921. Hitler also spoke at the Sängerhalle on May 29, 1923 and July 6, 1923. The Sängerhalle was located near the area in front of the Congress Hall today. The creation of a local SA group in Augsburg dated to November 1922 after the party had requested protection at a meeting which resulted in nearly fifty men from Munich being sent, who arrived at the station with flags and singing. It was claimed that the local SA group passed its baptism of fire in the Ludwigsbau on March 2, 1923. The Ludwigsbau at the time stood where the congress hall is today; demolished in 1965 due to the perceived danger of collapse of its dome. It was in 1923 that communists prevented the Nazi speaker from talking, leading to beer steins being thrown before a general brawl arose. The police cleared the hall and the mêlée continued outside spreading to Königsplatz.

|

| Adolf-Hitler-Platz and Annastraße |

From

1929 an ϟϟ group was established in Augsburg under the orders of

Himmler during a stay in the town. At first it consisted of ten men but

by the beginning of 1933 there were almost 500. In 1931 the notorious

Hans Loritz took over the ϟϟ leadership.On September 8, 1930 Hitler

spoke again at the Sängerhalle. This was during a time of increased

violence. Between 1930 to 1932 there were 440 public meetings and

demonstrations in Augsburg. One Nazi march was disrupted when Christmas

tree balls filled with gasoline were thrown into the torchlight

procession leading to SA, ϟϟ and Mounted Police beating up bystanders.

As flower pots flew a chant sounded: "Workers: let flowers speak." Augsburger police director Dr. Ernst Eichner

on January 23 1933- exactly a week before Hitler was appointed

Chancellor- declared that it was impossible for the police to protect

Nazi marches, because they allegedly did not disturb public safety.

Eichner did refer to the Nazi tactic during street fights in which the

police had to stand and salute immediately when the national anthem was

played. The report was fatal to Eichner- despite joining the Nazis in

March 33 to go so far as joining the Ministry of the Interior, Hitler

was informed of this report and declared how upset he was that "this

honourless characterless lumpen was still in government service."

Eichner was sent to Dachau in so-called protective custody, but was

released after a few days. On April 16, 1932 Hitler spoke twice in

Augsburg, at the Ludwigsbau and Sängerhalle, and on November 5 he again

attended a Nazi demonstration. On May 1, 1933, the big May Day of the

Nazis was to take place at the Sängerhalle. The hall was decorated with

countless swastika flags. However, in the early morning hours the hall

burned down completely. Raids and arrests in the poor quarters and

communist quarters took place. Thus Augsburg had its own local version

of the Reichstag fire. To this day no-one knows whether it was

accidental or the act either of a single person or of Nazi opponents.

Königsplatz

on the right after it had been renamed Adolf-Hitler-Platz. As early as

April 30, 1933 , the city council decided to rename Königsplatz to Adolf

Hitler Platz. In 1906, Hugo Landauer opened the "Hugo Landauer

Department Store, Manufactured Goods" on the corner of Königsplatz and

Bürgermeister-Fischer-Straße which would eventually become the leading

department store in Augsburg and Swabia and a major training facility.

After the call for a boycott in 1933, followed by graffiti and massive

pressure on Jewish businesses, the department store was sold to Albert

Golisch in 1934 and renamed "Zentral-Kaufhaus". On the third floor of

the Königsbau, towards Königsplatz, was the restaurant of the siblings

Josephine, Rosa and Pauline Bollak. On April 30, 1939, the "Law on

Tenancy Agreements with Jews" (JudenMietG) came into force which

resulted in the restaurant having to close on October 15, 1939 and the

three sisters evicted. They were housed at Hallstraße 14 - known as the

"Jewish house". Rosa died in Augsburg in 1941 whilst her two sisters

were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp the following

year where they were murdered.

Königsplatz

on the right after it had been renamed Adolf-Hitler-Platz. As early as

April 30, 1933 , the city council decided to rename Königsplatz to Adolf

Hitler Platz. In 1906, Hugo Landauer opened the "Hugo Landauer

Department Store, Manufactured Goods" on the corner of Königsplatz and

Bürgermeister-Fischer-Straße which would eventually become the leading

department store in Augsburg and Swabia and a major training facility.

After the call for a boycott in 1933, followed by graffiti and massive

pressure on Jewish businesses, the department store was sold to Albert

Golisch in 1934 and renamed "Zentral-Kaufhaus". On the third floor of

the Königsbau, towards Königsplatz, was the restaurant of the siblings

Josephine, Rosa and Pauline Bollak. On April 30, 1939, the "Law on

Tenancy Agreements with Jews" (JudenMietG) came into force which

resulted in the restaurant having to close on October 15, 1939 and the

three sisters evicted. They were housed at Hallstraße 14 - known as the

"Jewish house". Rosa died in Augsburg in 1941 whilst her two sisters

were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp the following

year where they were murdered.  Propaganda

during the Reichstag elections of November 12, 1933. The sign above the

clock reads "Wir wollen kein Volk minderen Rechts sein." After being appointed Chancellor, the Nazis celebrated in Augsburg as in the rest of the country with torches and parades. On February 1, the Augsburger Nationalzeitung wrote how "[t]he brown soldiers celebrated the victory of their leader by conquering the streets that were previously closed by the spell. In long rows, the brown crowd marched through Hermanstraße, Hallstraße, Maximilianstraße, Moritzplatz, Bürgermeister-Fischer-Straße, Königsplatz, Fuggerstrasse with music. For the first time the step of Hitler's battalions sounded in these streets." Due to the emergency decree for the protection of the German people, all communist events were banned and their press suppressed. Even the SPD was affected- their paper The Augsburg Swabian People's Daily was banned on March 10. Despite this, the Nazis managed only 44% nationwide support in this last election; it was even worse for the Nazis in Augsburg as they managed only 32% mostly from the brown strongholds of the Südend (Hochfeld, Bismarckviertel, Antons, Thelottsviertel) as well as in the Spickel and Hochzoll where they achieved results over 40%. The democratic parties SPD and BVP together had a clear majority. On March 9, four days after the Reichstag election, Hans Loritz hoisted the Nazi flag on the Perlachturm at four o'clock in the morning with four SA and ϟϟ men. In the morning Gauleiter Wahl then occupied the town hall, where he himself was employed as chancellery secretary, and from the balcony also had the party flag, the white-blue and the black-and-white-red raised, symbolising the Nazi revolution. Mayor Bohl and Council of Elders protested, but they left it at that. No protests made about trespassing, no informing the police; the flags stayed. Terror began to spread to the city government.

Propaganda

during the Reichstag elections of November 12, 1933. The sign above the

clock reads "Wir wollen kein Volk minderen Rechts sein." After being appointed Chancellor, the Nazis celebrated in Augsburg as in the rest of the country with torches and parades. On February 1, the Augsburger Nationalzeitung wrote how "[t]he brown soldiers celebrated the victory of their leader by conquering the streets that were previously closed by the spell. In long rows, the brown crowd marched through Hermanstraße, Hallstraße, Maximilianstraße, Moritzplatz, Bürgermeister-Fischer-Straße, Königsplatz, Fuggerstrasse with music. For the first time the step of Hitler's battalions sounded in these streets." Due to the emergency decree for the protection of the German people, all communist events were banned and their press suppressed. Even the SPD was affected- their paper The Augsburg Swabian People's Daily was banned on March 10. Despite this, the Nazis managed only 44% nationwide support in this last election; it was even worse for the Nazis in Augsburg as they managed only 32% mostly from the brown strongholds of the Südend (Hochfeld, Bismarckviertel, Antons, Thelottsviertel) as well as in the Spickel and Hochzoll where they achieved results over 40%. The democratic parties SPD and BVP together had a clear majority. On March 9, four days after the Reichstag election, Hans Loritz hoisted the Nazi flag on the Perlachturm at four o'clock in the morning with four SA and ϟϟ men. In the morning Gauleiter Wahl then occupied the town hall, where he himself was employed as chancellery secretary, and from the balcony also had the party flag, the white-blue and the black-and-white-red raised, symbolising the Nazi revolution. Mayor Bohl and Council of Elders protested, but they left it at that. No protests made about trespassing, no informing the police; the flags stayed. Terror began to spread to the city government.  On March 9 the SA and ϟϟ were declared auxiliary police- in Augsburg this translated into thirty ϟϟ and seventy SA men, leading to the real start of the harassment of political opponents. Four days later at the Siegesdenkmal in Fronhof they burned the Black-Red-Gold flags of the Republic. Mayor Bohl and other representatives of the governments of Swabia and Neuburg were present as invited guests. As a result of their complicity, the Nazis, as their newspaper rejoiced, received "state sanction" at a time when the majorities in city council and city government were still in favour of democratic parties.

On March 9 the SA and ϟϟ were declared auxiliary police- in Augsburg this translated into thirty ϟϟ and seventy SA men, leading to the real start of the harassment of political opponents. Four days later at the Siegesdenkmal in Fronhof they burned the Black-Red-Gold flags of the Republic. Mayor Bohl and other representatives of the governments of Swabia and Neuburg were present as invited guests. As a result of their complicity, the Nazis, as their newspaper rejoiced, received "state sanction" at a time when the majorities in city council and city government were still in favour of democratic parties. In May, the SPD, which had previously been excluded from almost all municipal committees, left the city council under pressure from the national socialists, on July 5 the BVP followed. The deputies of the DNVP joined the Nazi faction. At the council meeting of April 28, the second mayor of the SPD, Friedrich Ackermann, was formally retired and Nazi Josef Mayr, who had already taken the office in advance, was elected new mayor. On July 31, the Lord Mayor Otto Bohl (BVP) was finally dismissed and replaced at the city council meeting on August 3 by Nazi Edmund Stoeckle, the mayor of Lindenberg in the Allgäu. Stoeckle, however, could not possibly gain the confidence of the party leadership and was replaced by Josef Mayr in December 1934. The takeover of power in the city was thus completed. As early as March 9, communist officials were held in "protective". Whilst the arrests were initially directed against Communists and Social Democrats, Jews and other disobedient persons, as well as members of the BVP, quickly became targeted. The fire of the Sängerhalle (today's Wittelsbacher Park) on April 30, 1934 was also a cause of a wave of arrests. When Bavaria was then divided into six Gaue, Augsburg became the capital of the Gaues Schwaben.

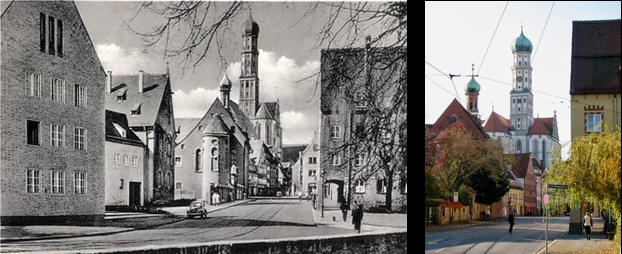

Looking at Jakobskirche from the Jakobertor; the view from the other direction is seen below comparing the destruction postwar with today. The city of Augsburg made Hitler an honorary citizen on April 25, 1935. Up until then such honours were given only at the end of a career. On September 25 that year Hitler visited the Golden Hall of the town hall with Mayor Mayr, Mayor Kellner, Obergruppenfuehrer Brückner, Schaub and Gauleiter Karl Wahl. On November 21 and 22, 1937 Hitler arrived at the Hotel Drei Mohren where he presented himself to his supporters on the balcony. In the presence of Prof. Giesler, Prof. Speer, city councillor Sametschek, mayor Kellner, Kreisleiter Schneider, Mayor Mayr and Gauleiter Karl Wahl, building plans for Augsburg's future as Gau capital were again presented to Hitler. Hitler later that evening attended a performance in the converted and expanded Theatre Augsburg with the Lord Mayor, Lieutenant General, and Gauleiter Karl Wahl. Hitler also visited the Messerschmitt works accompanied by Messerschmitt, director Henze, Obergruppenführer Brückner, Lieutenant General Bergmann, and Lieutenant-General Udet. At night, Hitler received a "tattoo" from the Wehrmacht in front of the Hotel Drei Mohren.

The planned gauforum. Königsplatz

was renamed Adolf-Hitler-Platz; since this street was created after the

demolition of the city walls after 1860, it had been created in the

style of the time as a broad boulevard and was therefore suitable for

the Nazis' mass marches. In Hitler's plans, this axis, which continues

straight to Theodor-Heuss-Platz (then Benito-Mussolini-Platz) and

running parallel to the "old" boulevard Karolinen-Maximilianstraße,

would become the new deployment arena in the course of the planned

Gauforums. Hitler had planned for Augsburg a monumental axis. After the Sängerhalle

had burned down on May 1, 1934, the city issued an architectural

competition. The first prize went to the design of the young Augsburg

architect Thomas Wechs who would go on to build many Augsburg churches

after the war. Wechs's plan provided for a modern construction with

nineteen narrow, high windows in Wittelsbacher Park, where the hotel

tower stands today. Hitler, presented with the draft, expressed

his displeasure and drew his ideas in the presence of the architect with

red pencil in the draft to produce a far more massive construction. In

1937 Hitler informed Wahl and Mayr that he wanted to equip the Gau

capital Augsburg with a completely new large Gauforum. He commissioned his favourite architect Hermann Giesler, recently responsible for the

Ordensburg Sonthofen. The planned Gauforum was to be located on a

48-metre-wide boulevard beginning at the Stadttheater and leading arross

Königsplatz and today's Konrad Adenauer Allee to the Theodor Heuss

platz. The actual centre would consist of a huge meeting hall for 20,000

people, a gigantic parade ground 165 metres by 140 metres surrounded by

arcades, and finally a party gau house with two courtyards and four 43

metre-high corner towers. A 116 metre high bell tower was supposed to tower

over all other towers of the city- Ulrich, Perlach, cathedral.

The monstrous structures were to be built south of the Königsplatz,

west of the Konrad Adenauer Allee / Schießgrabenstraße. All of

Beethovenviertel would have been demolished, including of course the

synagogue. The city had to acquire nearly 100 plots, demolishing 66

buildings in the process. Although the south of Augsburg had areas

available that could have been cultivated without cultural vandalism,

the idea was to build a boulevard which would overshadow the historic

mass and height of the past. The soil level was higher by nature, but

would still be artificially raised. Kreisleiter Schneider admitted in

his report to the Gauleiter that narrow-minded citizens reject all new

things, and the general opinion was that the city needed more housing

than monstrous palaces. Nevertheless, in the autumn of 1939 the

foundation stone was to have been lain but for the outbreak of the war.

Fuggerstrasse had already been cleared of its front gardens and trees

along the avenue- they are missing today. It was all estimated to cost

166 million RM. At a time when a house could be built for 10,000 RM,

considering the necessary relocation of the station and the district

heating plant, 200 millions would not have sufficed. Nevertheless, the

plans were under the special protection of Hitler; only Weimar, Hamburg

and Munich were so sponsored.

Hitler at the Augsburger Hauptbahnhof November 21, 1937 and me today, remarkably unchanged. The occasion of Hitler's visit was the fifteenth anniversary of the NSDAP Ortsgruppe. In his speech he addressed his opponents within Germany, denying any “right to criticism,” stating that "[w]e have criticisms, too, but here the superiors criticise the subordinates and not the subordinates their superiors!" He then described the new tasks faced and addressed the subject of Lebensraum:

|

| In front of the Weberhaus behind the Merkurbrunnen |

Hitler at the Augsburger Hauptbahnhof November 21, 1937 and me today, remarkably unchanged. The occasion of Hitler's visit was the fifteenth anniversary of the NSDAP Ortsgruppe. In his speech he addressed his opponents within Germany, denying any “right to criticism,” stating that "[w]e have criticisms, too, but here the superiors criticise the subordinates and not the subordinates their superiors!" He then described the new tasks faced and addressed the subject of Lebensraum:

I may say so myself, my old Party Comrades: our fight was worth it after all. Never before has a fight commenced with as much success as ours. In these fifteen years, we have taken on a tremendous task. The task blessed our efforts. Our efforts were not in vain, for from them has ensued one of the greatest rebirths in history. Germany has overcome the great catastrophe and awakened from it to a better and new and strong life. That we can say at the end of these fifteen years. And there lies the reward for every single one of you, my old Party Comrades! When I look back on my own life, I can certainly say that it has been an immeasurable joy to be able to work for our Volk in this great age. It is truly a wonderful thing after all when Fate chooses certain people who are allowed to devote themselves to their Volk. Today we are facing new tasks. For the Lebensraum of our Volk is too confined. The world is attempting to disassociate itself from dealing with these problems and answering these questions. But it will not succeed! One day the world will be forced to take our demands into consideration. I do not doubt for a second that we will procure for ourselves the same vital rights as other peoples outside the country in exactly the same way as we were able to lead it onwards within. I do not doubt that this vital right of the German Volk, too, will one day be understood by the whole world! I am of the conviction that the most difficult preliminary work has already been accomplished. What is necessary now is that all National Socialists recall again and again the principles with which we grew up. If the whole Party and hence the whole nation stands united behind the leadership, then this same leadership, supported by the joined forces of a population of sixty-eight million, ultimately personified in its Wehrmacht, will be able to successfully defend the interests of the nation and also to successfully accomplish the tasks assigned to us!

Donarus (977-978)

The main street in 1941 taken from the Hercules fountain, the year that Rudolf Hess flew from an aerodrome near Augsburg to the United Kingdom at 17.45 on Saturday, May 10 alone over the North Sea to Scotland to meet the Duke of Hamilton before crashing in Eaglesham in an attempt to mediate the end of the European front of the war and join sides for the upcoming Russian Campaign. Augsburg

was historically a militarily important city due to its strategic

location. During the German re-armament before the war, the

Wehrmacht enlarged Augsburg's one original barracks to three:

Somme Kaserne (housing Wehrmacht Artillerie-Regiment 27); Arras Kaserne

(housing Wehrmacht Infanterie Regiment 27) and Panzerjäger Kaserne

(housing Panzerabwehr-Abteilung 27 (later Panzerjäger-Abteilung 27).

Wehrmacht Panzerjäger-Abteilung 27 was later moved to Füssen. During the war, one subcamp of the Dachau concentration camp was located

outside Augsburg, supplying approximately 1,300 forced labourers to

local military-related industry, most especially the Messerschmitt AG

military aircraft firm headquartered in Augsburg. The early history of the Messerschmitt factory in Augsburg, from its foundation in the aftermath of the First World War to the outbreak of the Second World War, demonstrates how industrial enterprises in Germany aligned themselves with the ambitions of the Nazi regime well before the full-scale war began. Established in 1923 as Bayerische Flugzeugwerke AG (BFW), the company initially struggled to find its footing in the post-Versailles aviation market. The Treaty of Versailles had imposed severe restrictions on German aviation, including a ban on the production of military aircraft, which meant that companies like BFW had to focus on civilian and sport aviation.The aviation industry, once a symbol of German technological prowess, was reduced to producing light planes for private use, and demand was minimal in a nation still grappling with the economic fallout of the war. Augsburg, an industrial city with a long tradition of craftsmanship and manufacturing, wasn't immune to these economic difficulties. The region's industries, including BFW, faced the combined challenges of a depressed economy, a lack of investment, and restrictions on technological innovation. In this climate, BFW was on the verge of collapse by the late 1920s.

The turning point came with the arrival of a young, ambitious aeronautical engineer named Willy Messerschmitt, who joined the company as chief designer in 1927. Messerschmitt's early career was defined by his innovative approach to aircraft design, emphasising lightweight structures, aerodynamic efficiency, and modular construction methods that would later become hallmarks of his most successful models. His initial designs, such as the M17 and M18, were commercial failures, but they laid the groundwork for the company’s future direction. Messerschmitt’s vision went beyond the limited civilian market; he anticipated that Germany would eventually re-enter the military aviation arena, despite the restrictions imposed by Versailles. His persistence paid off in 1931 when BFW, buoyed by new investment, managed to survive a period of insolvency and restructured its operations. Messerschmitt’s influence grew, and by 1933, he had become the dominant figure within the company.

|

| At Metzgplatz with Rathausplatz behind before the war and me today |

The year 1933 marked a seismic shift in Germany’s political landscape with Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor and the rapid consolidation of Nazi power. The new regime prioritised rearmament as a cornerstone of its policies, and the aviation industry was seen as critical to restoring Germany’s military strength. Hitler’s government openly defied the Treaty of Versailles, re-establishing the Luftwaffe and directing significant resources towards developing a modern air force.

This change in policy created enormous opportunities for companies like BFW, which had the expertise and ambition to capitalise on the regime’s demands for military aircraft. Recognising the potential for growth under the new political order, Messerschmitt aligned his company’s goals with those of the Nazi regime. His designs quickly gained the attention of senior Luftwaffe officials, particularly the Bf 108, a sleek, four-seater aircraft that showcased the company’s engineering capabilities. The success of the Bf 108 led to a pivotal contract for the development of a new fighter aircraft, which would become the Bf 109. The Bf 109 would go on to become one of the most iconic aircraft of the Second World War, but its origins can be traced back to the strategic decisions made in Augsburg during the early years of the Nazi regime. By 1936, Messerschmitt had taken full control of the company, which was officially renamed Messerschmitt AG. The reorganisation reflected the company’s growing importance within the Nazi war economy. The Messerschmitt factory in Augsburg became a hub of aircraft production, with the city’s skilled workforce and industrial infrastructure playing a crucial role in meeting the demands of the Luftwaffe. The factory expanded rapidly, with new facilities constructed to accommodate the increasing production of military aircraft. The German government’s investment in Messerschmitt AG was substantial, with contracts awarded for the mass production of the Bf 109 and other military aircraft. The relationship between Messerschmitt and the Nazi regime was mutually beneficial: the government secured a reliable supply of advanced fighter planes, while Messerschmitt AG grew into one of Germany’s leading aerospace companies. Messerschmitt himself was a complex figure, both a brilliant engineer and an opportunist who recognised the benefits of aligning with the Nazi state. His ambition to become a major player in the aviation industry was realised through his willingness to collaborate with the regime’s rearmament policies. The Messerschmitt factory’s growth also had a significant impact on Augsburg’s local economy. The factory became one of the city’s largest employers, providing jobs to thousands of workers and contributing to the city’s economic recovery after years of stagnation. However, the expansion of the factory also tied Augsburg’s fortunes to the Nazi war machine. By 1939, the Messerschmitt factory in Augsburg had become one of the most important sites of aircraft production in Germany, producing hundreds of Bf 109 fighters that would be used in the early stages of the Second World War. The factory’s transformation from a struggling civilian aircraft manufacturer to a key player in Germany’s rearmament highlights the role of industrial enterprises in facilitating the Nazi regime’s military ambitions. The story of the Messerschmitt factory before 1939 is one of adaptation and opportunism, with the city of Augsburg playing a central role in Germany’s preparations for war.

|

| Looking at Rathausplatz from the Perlachturm in 1940 & today |

This is also the

hometown of Jakob Grimminger, famous for having been awarded the honour

of carrying the blood-stained Blutfahne from the Munich putsch.

.gif) In 1941, Rudolf Hess without Hitler's permission secretly took off from a local airport. The Reichswehr Infanterie Regiment 19 was stationed in Augsburg and became the base unit for the Wehrmacht Infanterie Regiment 40, a subsection of the Wehrmacht Infanterie Division 27 (which later became the Wehrmacht Panzerdivision 17). Elements of Wehrmacht II Battalion of Gebirgs-Jäger-Regiment 99 (especially Wehrmacht Panzerjäger Kompanie 14) was composed of parts of the Wehrmacht Infanterie Division 27. The Infanterie Regiment 40 remained in Augsburg until the end of the war, finally surrendering to the Americans when in 1945, the American Army occupied the heavily bombed and damaged city. Following the war, the three barracks would change hands confusingly between the American and Germans, finally ending up in American hands for the duration of the Cold War. The former Wehrmacht Kaserne became the three main American barracks in Augsburg: Reese, Sheridan and FLAK. US Base FLAK had been an anti-aircraft barracks since 1936 and US Base Sheridan "united" the former infantry barracks with a smaller Kaserne for former Luftwaffe communications units. The American military presence in the city started with the 11th Airborne Division, followed by the 24th Infantry Division, the American Army Seventh Corps Artillery, USASA Field Station Augsburg and finally the 66th Military Intelligence Brigade, which returned the former Kaserne to German hands in 1998. Originally the Heeresverpflegungshauptamt Südbayern and an Officers' caisson existed on or near the location of Reese-Kaserne, but was demolished by the occupying Americans.

In 1941, Rudolf Hess without Hitler's permission secretly took off from a local airport. The Reichswehr Infanterie Regiment 19 was stationed in Augsburg and became the base unit for the Wehrmacht Infanterie Regiment 40, a subsection of the Wehrmacht Infanterie Division 27 (which later became the Wehrmacht Panzerdivision 17). Elements of Wehrmacht II Battalion of Gebirgs-Jäger-Regiment 99 (especially Wehrmacht Panzerjäger Kompanie 14) was composed of parts of the Wehrmacht Infanterie Division 27. The Infanterie Regiment 40 remained in Augsburg until the end of the war, finally surrendering to the Americans when in 1945, the American Army occupied the heavily bombed and damaged city. Following the war, the three barracks would change hands confusingly between the American and Germans, finally ending up in American hands for the duration of the Cold War. The former Wehrmacht Kaserne became the three main American barracks in Augsburg: Reese, Sheridan and FLAK. US Base FLAK had been an anti-aircraft barracks since 1936 and US Base Sheridan "united" the former infantry barracks with a smaller Kaserne for former Luftwaffe communications units. The American military presence in the city started with the 11th Airborne Division, followed by the 24th Infantry Division, the American Army Seventh Corps Artillery, USASA Field Station Augsburg and finally the 66th Military Intelligence Brigade, which returned the former Kaserne to German hands in 1998. Originally the Heeresverpflegungshauptamt Südbayern and an Officers' caisson existed on or near the location of Reese-Kaserne, but was demolished by the occupying Americans.

The Augustus statue at Maximiliansplatz surrounded by Nazi flags and today, and being dismantled in 1940 for safety during the war shown below on the right. The fountain was erected between 1588 and 1594 by Hubert Gerhard for the 1600th anniversary of the city. It is the oldest and most figurative of the three magnificent Augsburg fountains and is located on Rathausplatz, dominated by a 2.5 metre-high figure of Augustus. The emperor was portrayed as a man of about fifty who raises his hand in "adlocutio" as emperors traditionally did when they began a solemn address to their army. The head of the emperor wreaths a laurel wreath, which stands for fame, honour and peace, referring to the so-called Pax Augustana.  On the tunic that Augustus wears lion heads are depicted as a symbol for his strength, and dolphins with a trident as a symbol for quick decisions. In addition, tritons and, under the feet of the statue the pine cone- the symbol of Augsburg- are shown. Two Capricorn skulls indicate that Augustus was born in the zodiac sign of Capricorn. Art historians claim to have established that the Augustus figure in the fountain is more like the pointed nose of his successor Vespasian. The Augustus fountain is not directly opposite the Augsburg town hall but rather in front of the neighbouring Perlachturm building. The off-centre position of the fountain on the square is due to the fact that the town hall square was originally much smaller than it is today and only occupied the northern part of today's square. It was not enlarged to its current dimensions until the early 1960s, when the ruins from the air raids of the war were removed. The well was also moved a few meters to the north. The Augustus figure has become the most damaged over the centuries because it has the most unfavourable alloy of all the figures on the fountain comprising of 88% copper, four percent tin, five percent lead and 1.5% zinc. To save the statue, it was renovated in 1993 and the original was replaced by a copy. Today the original of the Augustus statue is housed in the inner courtyard of the Maximilian Museum, which is roofed with glass. The replacement copy was financed with funds from the Messerschmitt Foundation; its basins and pillars are also copies. For Augsburg's 2000th anniversary, the wrought iron grille by Georg Scheff was erected around the fountain. In addition to Augustus, there are four other figures that symbolise the four rivers of Augsburg: the Lech, Wertach, Singold and Brunnenbach. Some also assign the four seasons to the figures: the two women spring and summer, the two male deities autumn and winter.

On the tunic that Augustus wears lion heads are depicted as a symbol for his strength, and dolphins with a trident as a symbol for quick decisions. In addition, tritons and, under the feet of the statue the pine cone- the symbol of Augsburg- are shown. Two Capricorn skulls indicate that Augustus was born in the zodiac sign of Capricorn. Art historians claim to have established that the Augustus figure in the fountain is more like the pointed nose of his successor Vespasian. The Augustus fountain is not directly opposite the Augsburg town hall but rather in front of the neighbouring Perlachturm building. The off-centre position of the fountain on the square is due to the fact that the town hall square was originally much smaller than it is today and only occupied the northern part of today's square. It was not enlarged to its current dimensions until the early 1960s, when the ruins from the air raids of the war were removed. The well was also moved a few meters to the north. The Augustus figure has become the most damaged over the centuries because it has the most unfavourable alloy of all the figures on the fountain comprising of 88% copper, four percent tin, five percent lead and 1.5% zinc. To save the statue, it was renovated in 1993 and the original was replaced by a copy. Today the original of the Augustus statue is housed in the inner courtyard of the Maximilian Museum, which is roofed with glass. The replacement copy was financed with funds from the Messerschmitt Foundation; its basins and pillars are also copies. For Augsburg's 2000th anniversary, the wrought iron grille by Georg Scheff was erected around the fountain. In addition to Augustus, there are four other figures that symbolise the four rivers of Augsburg: the Lech, Wertach, Singold and Brunnenbach. Some also assign the four seasons to the figures: the two women spring and summer, the two male deities autumn and winter.

On the tunic that Augustus wears lion heads are depicted as a symbol for his strength, and dolphins with a trident as a symbol for quick decisions. In addition, tritons and, under the feet of the statue the pine cone- the symbol of Augsburg- are shown. Two Capricorn skulls indicate that Augustus was born in the zodiac sign of Capricorn. Art historians claim to have established that the Augustus figure in the fountain is more like the pointed nose of his successor Vespasian. The Augustus fountain is not directly opposite the Augsburg town hall but rather in front of the neighbouring Perlachturm building. The off-centre position of the fountain on the square is due to the fact that the town hall square was originally much smaller than it is today and only occupied the northern part of today's square. It was not enlarged to its current dimensions until the early 1960s, when the ruins from the air raids of the war were removed. The well was also moved a few meters to the north. The Augustus figure has become the most damaged over the centuries because it has the most unfavourable alloy of all the figures on the fountain comprising of 88% copper, four percent tin, five percent lead and 1.5% zinc. To save the statue, it was renovated in 1993 and the original was replaced by a copy. Today the original of the Augustus statue is housed in the inner courtyard of the Maximilian Museum, which is roofed with glass. The replacement copy was financed with funds from the Messerschmitt Foundation; its basins and pillars are also copies. For Augsburg's 2000th anniversary, the wrought iron grille by Georg Scheff was erected around the fountain. In addition to Augustus, there are four other figures that symbolise the four rivers of Augsburg: the Lech, Wertach, Singold and Brunnenbach. Some also assign the four seasons to the figures: the two women spring and summer, the two male deities autumn and winter.

On the tunic that Augustus wears lion heads are depicted as a symbol for his strength, and dolphins with a trident as a symbol for quick decisions. In addition, tritons and, under the feet of the statue the pine cone- the symbol of Augsburg- are shown. Two Capricorn skulls indicate that Augustus was born in the zodiac sign of Capricorn. Art historians claim to have established that the Augustus figure in the fountain is more like the pointed nose of his successor Vespasian. The Augustus fountain is not directly opposite the Augsburg town hall but rather in front of the neighbouring Perlachturm building. The off-centre position of the fountain on the square is due to the fact that the town hall square was originally much smaller than it is today and only occupied the northern part of today's square. It was not enlarged to its current dimensions until the early 1960s, when the ruins from the air raids of the war were removed. The well was also moved a few meters to the north. The Augustus figure has become the most damaged over the centuries because it has the most unfavourable alloy of all the figures on the fountain comprising of 88% copper, four percent tin, five percent lead and 1.5% zinc. To save the statue, it was renovated in 1993 and the original was replaced by a copy. Today the original of the Augustus statue is housed in the inner courtyard of the Maximilian Museum, which is roofed with glass. The replacement copy was financed with funds from the Messerschmitt Foundation; its basins and pillars are also copies. For Augsburg's 2000th anniversary, the wrought iron grille by Georg Scheff was erected around the fountain. In addition to Augustus, there are four other figures that symbolise the four rivers of Augsburg: the Lech, Wertach, Singold and Brunnenbach. Some also assign the four seasons to the figures: the two women spring and summer, the two male deities autumn and winter.

The turn of St. Michael from the Zeughaus (armoury) to be removed, shown then and now

The Herkulesbrunnen then and now showing the repositioning of the statue postwar. The magnificent fountain was made between 1596 and 1600 by Adriaen de Vries and shows the Hercules fighting the Hydra, intended to symbolise the wealth of Augsburg being based on the use of water power. According to Greek legend, Hercules needed the club of flames to scorch the roots of the severed heads and thus prevent the hydra from sprouting new heads and thus here a depiction of the victory of man over the wild power of water and the power of fire. Others see a psychological dimension in it, interpreting it as the conquest of wild human passions only through which humans come to wealth and a good life. In 1940 the figures of the Hercules Fountain as well as those of other fountains were sent to the Ottobeuren monastery to protect them from the bombing. From there the naiads of the Hercules fountain were kept in a stairwell. In 1950 the figures of the Hercules Fountain were brought back from the monastery and returned to their original places by the well.

The Maypole in front of St. Ulrich's and St. Afra's Abbey May 1, 1935 and at the end of Margaretenstraße

The Mercury statue on Maximilianstraße near the Catholic Church of St. Moritz at the junction with the Burgermeister-Fischer-Straße being returned July 31, 1947 and taken away sixty years later for refurbishment. The fountain on Moritzplatz is one of the three magnificent fountains in Augsburg, along with the Augustus fountain and Hercules fountain. It was created in 1596-1599 by Adriaen de Vries in the Renaissance style. Its main character is the Roman god of commerce, Mercury. As the god of trade, Mercury is supposed to draw attention to the importance of the city as a trading metropolis. The 2.5 metre high fountain group is dominated by Mercurius who holds a serpent's staff, symbol of luck and peace, in his right hand and wears a winged helmet on his head. The winged cupid, equipped with a bow, appears to be loosening or tying the winged shoe of the god Mercurius. The type of "Mercurio volante" coined by Giovanni da Bologna can be regarded as a model for the fountain figure of Mercury but the Augsburger Merkur seems to remain between hurrying and staying. The four-sided fountain stands in a decagonal marble basin. Two rocaille cartouches from 1752 are attached to the cornice of the fountain. The water flows in a thin stream from the bronzes on the pillar: two dog heads, two Medusa heads, two lion masks and four eagle heads, symbols of the dangers that threaten trade and traffic.

The St. George fountain, dating from 1565. St. George appears in a harness from the 16th century and fights a dragon. The figure's equestrian armour was probably cast from tournament armour and corresponds in detail to templates from the period between 1550 and 1560. Over time, the figure of St. George has changed location in Augsburg several times. The figure of St. George had earlier adorned a fountain on Metzgplatz between 1833 and 1945 before its restoration in 1961 when it was moved to a high fountain column in front of the St. Jakob Church in Jakobervorstadt in connection with the new construction of the east-west traffic axis through the city centre. Walther Schmidt , who was in charge of city planning at the time, agreed and placed the fountain figure on a high pillar in order to improve the effect of the delicate figure in the broad street space. An oval basin with a water feature was created below the figure. On

the base of the fountain there are masks that spew water in all

directions which are based on employees of the city's structural

engineering department. Over the years, air pollution has caused increasing damage to the fountain figure. It wasn't until 1993 that St. George was relocated onto this newly designed fountain and is now back on Metzplatz. It's clear by looking at the buildings in the background that he hasn't been replaced at the original spot.

Augsburg

suffered serious damage in the war due to air raids, as

the city was a military target of allied bomber organisations with

production sites of important armaments companies (including

Messerschmitt AG and MAN). Already in October 1939 the air war reached Augsburg for the first time. But it was not until April 1942 that the British bombers managed the first heavy blow against the Augsburg armaments industry. Eight British Lancasters attack the MAN, the main production site for submarine diesel engines. In Augsburg there was amazement and shame that the birthplace of the allegedly best fighter plane in the world in the vicinity of an airfield left the city defenceless against such attacks. But then, as Brexit and covid has shown, the Germans have an innate dispensation to constantly underestimate the British to their cost. That - in conjunction with the first report of a dozen killed - was a psychological shock, which was only partially offset by the announcement a few weeks later that the MAN factory again produced as many engines as before. In all, Augsburg was bombed more than ten times,

twice in attacks of greater effect: on April 17, 1942, the goal was

MAN's submarine engine production.

Ludwigstraße before the RAF visited and today

On Friday, February 25, 1944, 200 American bombers appeared at 14.00 and attacked the Messerschmittwerke. 110 lives were lost, including whole families in the neighbouring settlement houses and about fifty concentration camp inmates. 60% of the plant was destroyed. At 22.00 sirens howled again as 248 British bombers created a 40-minute inferno of aerial mines and incendiary bombs which additionally turned the debris field into a sea of flames. An hour later came the third wave of assault. Another 290 British bombers again created burning chaos for 45 minutes. The inner city (especially Karls-, Ludwigstraße and the area around Wertachbrucker Tor) as well as the Jakobervorstadt, Lechhausen and Haunstetten were the hardest hit. The bombs killed 730 people that night alone, including 285 women and 78 children. Amongst the victims were 27 people who had drowned in a buried cellar when the Lech Canal overflowed.

.gif) Adding to the 145 Allied airmen killed and the dead of the afternoon, the

totals of the dead rose to nearly a thousand. More than 80,000

Augsburgers became homeless with most fleeing their burning neighbourhoods at night or the next day. Finally on April 28, 1945, units of the 7th American

Army arrived in Augsburg without any resistance and established a base

with several barracks, which was only completely abandoned by the

withdrawal of the last troops in 1998. In order to defuse a 1.8-tonne bomb with 1.5

tonnes of explosives found on December 20, 2016 during construction work on

Jakoberwallstrasse, a mass excavation took place on Christmas day 2016, affecting 54,000 people. A two mile diameter zone evacuated

around the site of discovery in the historical centre.

Adding to the 145 Allied airmen killed and the dead of the afternoon, the

totals of the dead rose to nearly a thousand. More than 80,000

Augsburgers became homeless with most fleeing their burning neighbourhoods at night or the next day. Finally on April 28, 1945, units of the 7th American

Army arrived in Augsburg without any resistance and established a base

with several barracks, which was only completely abandoned by the

withdrawal of the last troops in 1998. In order to defuse a 1.8-tonne bomb with 1.5

tonnes of explosives found on December 20, 2016 during construction work on

Jakoberwallstrasse, a mass excavation took place on Christmas day 2016, affecting 54,000 people. A two mile diameter zone evacuated

around the site of discovery in the historical centre.

Ludwigstraße before the RAF visited and today

On Friday, February 25, 1944, 200 American bombers appeared at 14.00 and attacked the Messerschmittwerke. 110 lives were lost, including whole families in the neighbouring settlement houses and about fifty concentration camp inmates. 60% of the plant was destroyed. At 22.00 sirens howled again as 248 British bombers created a 40-minute inferno of aerial mines and incendiary bombs which additionally turned the debris field into a sea of flames. An hour later came the third wave of assault. Another 290 British bombers again created burning chaos for 45 minutes. The inner city (especially Karls-, Ludwigstraße and the area around Wertachbrucker Tor) as well as the Jakobervorstadt, Lechhausen and Haunstetten were the hardest hit. The bombs killed 730 people that night alone, including 285 women and 78 children. Amongst the victims were 27 people who had drowned in a buried cellar when the Lech Canal overflowed.

.gif) Adding to the 145 Allied airmen killed and the dead of the afternoon, the

totals of the dead rose to nearly a thousand. More than 80,000

Augsburgers became homeless with most fleeing their burning neighbourhoods at night or the next day. Finally on April 28, 1945, units of the 7th American

Army arrived in Augsburg without any resistance and established a base

with several barracks, which was only completely abandoned by the

withdrawal of the last troops in 1998. In order to defuse a 1.8-tonne bomb with 1.5

tonnes of explosives found on December 20, 2016 during construction work on

Jakoberwallstrasse, a mass excavation took place on Christmas day 2016, affecting 54,000 people. A two mile diameter zone evacuated

around the site of discovery in the historical centre.

Adding to the 145 Allied airmen killed and the dead of the afternoon, the

totals of the dead rose to nearly a thousand. More than 80,000

Augsburgers became homeless with most fleeing their burning neighbourhoods at night or the next day. Finally on April 28, 1945, units of the 7th American

Army arrived in Augsburg without any resistance and established a base

with several barracks, which was only completely abandoned by the

withdrawal of the last troops in 1998. In order to defuse a 1.8-tonne bomb with 1.5

tonnes of explosives found on December 20, 2016 during construction work on

Jakoberwallstrasse, a mass excavation took place on Christmas day 2016, affecting 54,000 people. A two mile diameter zone evacuated

around the site of discovery in the historical centre. .gif) The Stadttheater in August, 1934. From 1931 to 1936 Erich Pabst was the artistic director at the theatre. Whilst pretending to be absolutely politically neutral, his management was already strongly oriented towards the Nazis who purged and censored the theatre of those deemed enemies through the Nazi theatre law. Among those was Paul Frankenburger, a Jew who had served as Kapellmeister since 1924 before fleeing to British Palestine in 1933 under the name Paul Ben Haim. Under Pabst plans were drawn up to rebuild the theatre, equip it with a wider façade and thus give the planned monumental parade street leading to the Gauforum an appropriate face. To advance this project, Hitler himself came to the theatre on September 24, 1935. This renovation now became a top priority. In 1936 the new general manager, Nazi Party member Leon Geer, aligned the schedule more and more to Nazi guidelines. There was no longer any freedom of art. In 1936 Geer directed Schiller's Wilhelm Tell during which performance the actors implemented the Rütli oath as a Hitler salute. In 1937 the renovation of the theatre started.

The Stadttheater in August, 1934. From 1931 to 1936 Erich Pabst was the artistic director at the theatre. Whilst pretending to be absolutely politically neutral, his management was already strongly oriented towards the Nazis who purged and censored the theatre of those deemed enemies through the Nazi theatre law. Among those was Paul Frankenburger, a Jew who had served as Kapellmeister since 1924 before fleeing to British Palestine in 1933 under the name Paul Ben Haim. Under Pabst plans were drawn up to rebuild the theatre, equip it with a wider façade and thus give the planned monumental parade street leading to the Gauforum an appropriate face. To advance this project, Hitler himself came to the theatre on September 24, 1935. This renovation now became a top priority. In 1936 the new general manager, Nazi Party member Leon Geer, aligned the schedule more and more to Nazi guidelines. There was no longer any freedom of art. In 1936 Geer directed Schiller's Wilhelm Tell during which performance the actors implemented the Rütli oath as a Hitler salute. In 1937 the renovation of the theatre started.  The photo on the right shows Hitler in front of the Stadttheater on March 19, 1937. On the left is the Nazi mayor, Josef Mayer. The

man in the coat is Gauleiter Karl Wahl whilst that in uniform with the

tresses could either be Hitler's personal adjutant or the Augsburg

police chief ϟϟ Brigadefuhrer Bernhard Stark. It was in a speech at Augsburg on November 21 that

year that Hitler made the demand for colonies when he declared: "What

the world shuts its ears to today it will not be able to ignore in a

year's time. What it will not listen to now it will have to think about

in three years' time, and in five or six it will have to take into

practical consideration. We shall voice our demand for living-room in colonies more and more loudly till the world cannot but recognise our claim."

The photo on the right shows Hitler in front of the Stadttheater on March 19, 1937. On the left is the Nazi mayor, Josef Mayer. The

man in the coat is Gauleiter Karl Wahl whilst that in uniform with the

tresses could either be Hitler's personal adjutant or the Augsburg

police chief ϟϟ Brigadefuhrer Bernhard Stark. It was in a speech at Augsburg on November 21 that

year that Hitler made the demand for colonies when he declared: "What

the world shuts its ears to today it will not be able to ignore in a

year's time. What it will not listen to now it will have to think about

in three years' time, and in five or six it will have to take into

practical consideration. We shall voice our demand for living-room in colonies more and more loudly till the world cannot but recognise our claim." |

| Hitler attending a performance at its re-opening May 24, 1939 |

Hitler visited the construction site three times before it opened, which showed how important the renovation was to him. Hitler had Professor Paul Baumgarten extensively remodel and elegantly furnish the theatre by 1939 in time for Hitler's visit for its reopening. By this time Leon Geer, who had been loyal to the Nazis, was fired due to a lack of artistic quality and other allegations. Willy Becker replaced him only for the war to lead the Augsburg town administration to attempt to close the theatre. This was not done specifically due to Hitler's personal orders. Even when the war led to restrictions on stage operations in other cities, “Germany's most modern stage”, as the Augsburg Theatre was advertised, continued relatively unimpeded. For the Nazis in Augsburg, "[a] visit to the theatre is a cultural service to the people!" However, the shortage of staff due to conscription led to restrictions that were not planned. As early as the 1939-1940 season, only about half of the planned performances could take place. In 1941 Becker dared to have the comedy "Das Lebenslängliche Kind" performed by Erich Kästner who had been prohibited from writing. He simply gave the comedy writer the name Robert Neuner as a pseudonym. In the further course of the war, cheerful pieces were usually played to lighten the mood. Nazi organisations often had their own ideas which led the ensemble to perform in front of the troops or play in hospitals. With the bombing on the night of February 25, 1944, the Augsburg Theatre was completely destroyed leading the town to establish an alternative platform in the Ludwigsbau. On the instructions of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, the theatre closed in September 1944 which the director at the time, Walter Oehmichen, sought to prevent through an appeal to the mayor. My GIF on the right shows a Nazi demonstration outside the Stadttheater on March 23, 1933 and a neo-Nazi demonstration at the same site more recently on December 2, 2006.

Bürgermeister Kellner speaking in the Goldener Saal of the rathaus in 1934 during the so-called Machtergreifung. In March 1933 the Nazis symbollicaly took the town hall for themselves despite having no majority in the city council at the time. Without protest from the democratically elected city leaders, they hung the Nazi flag from its balcony. In the weeks that followed, they harassed communist and social democratic city councillors, but also those from the Bavarian People's Party (BVP). The city council gradually became an acclamation organ. The British attacked the city with bombers in the night of February 25-26, 1944 and destroyed almost the entire city centre. The town hall was also badly damaged in this bomb attack with only ruins left; everything was burned out inside. Looking at the reconstructed town hall in all its splendour today, one can hardly imagine such devastation as a result of the war. The façade was rebuilt soon after the war: between 1946 and 1948 the heavily destroyed town hall was secured with its second topping-out ceremony celebrated in May 1947.

Between 1950 to 1954, its external appearance was restored.

Elias Holl's masterpiece was considered one of the world's most

valuable town halls in terms of art history but, because it was

destroyed in the war, is largely a copy which is why it is not included

in the list of World Heritage Sites by Unesco. Before the war the town hall could only be seen between Philippine-Welser-Straße and Steingasse because of the dense and narrow development of the Rathausplatz. The façade renovation of the town hall was completed in 1955, when the 1000th anniversary of the battle of Lechfeld was held. When the interior work was largely completed, the somewhat restored town hall was inaugurated on April 18, 1962. Now all that was left was to restore the Golden Hall.

Between 1950 to 1954, its external appearance was restored.

Elias Holl's masterpiece was considered one of the world's most

valuable town halls in terms of art history but, because it was

destroyed in the war, is largely a copy which is why it is not included

in the list of World Heritage Sites by Unesco. Before the war the town hall could only be seen between Philippine-Welser-Straße and Steingasse because of the dense and narrow development of the Rathausplatz. The façade renovation of the town hall was completed in 1955, when the 1000th anniversary of the battle of Lechfeld was held. When the interior work was largely completed, the somewhat restored town hall was inaugurated on April 18, 1962. Now all that was left was to restore the Golden Hall.

On the right is the same room today, showing how much has been reconstructed from so little. Up until 1944, the ornate ceiling of the hall had hung from its wooden roof structure 27 chains. The renovation after the war led to it being attached to a steel stone ceiling. The gold leaf used on the ceiling is 23 1/2 carats and whilst solid walnut boards used to form the ceiling, today it is blockboard that has been glued with three millimetre thick walnut veneers. Along with the town hall, the Golden Hall also fell victim to British bombing. For many decades after the war, the hall remained an undignified makeshift room: instead of the magnificent coffered ceiling, a simple wooden ceiling was installed, the portals were plain wooden doors, the walls were plastered white and an asphalt ceiling had been spread out on the floor. This room was used as an exhibition space until the 1960s. It wasn't until 1957 that the town launched a competition to redesign the space based on the requirements that the space would not only be a reconstruction of the past, but "as before express the character and dignity of the city." 36 designs were submitted, but fortunately none was accepted because they allegedly interfered too much with the existing room structure. It wasn't until 1996 that the Golden Hall was officially returned to the public in its original state.

Between 1950 to 1954, its external appearance was restored.

Elias Holl's masterpiece was considered one of the world's most

valuable town halls in terms of art history but, because it was

destroyed in the war, is largely a copy which is why it is not included

in the list of World Heritage Sites by Unesco. Before the war the town hall could only be seen between Philippine-Welser-Straße and Steingasse because of the dense and narrow development of the Rathausplatz. The façade renovation of the town hall was completed in 1955, when the 1000th anniversary of the battle of Lechfeld was held. When the interior work was largely completed, the somewhat restored town hall was inaugurated on April 18, 1962. Now all that was left was to restore the Golden Hall.

Between 1950 to 1954, its external appearance was restored.

Elias Holl's masterpiece was considered one of the world's most

valuable town halls in terms of art history but, because it was

destroyed in the war, is largely a copy which is why it is not included

in the list of World Heritage Sites by Unesco. Before the war the town hall could only be seen between Philippine-Welser-Straße and Steingasse because of the dense and narrow development of the Rathausplatz. The façade renovation of the town hall was completed in 1955, when the 1000th anniversary of the battle of Lechfeld was held. When the interior work was largely completed, the somewhat restored town hall was inaugurated on April 18, 1962. Now all that was left was to restore the Golden Hall.On the right is the same room today, showing how much has been reconstructed from so little. Up until 1944, the ornate ceiling of the hall had hung from its wooden roof structure 27 chains. The renovation after the war led to it being attached to a steel stone ceiling. The gold leaf used on the ceiling is 23 1/2 carats and whilst solid walnut boards used to form the ceiling, today it is blockboard that has been glued with three millimetre thick walnut veneers. Along with the town hall, the Golden Hall also fell victim to British bombing. For many decades after the war, the hall remained an undignified makeshift room: instead of the magnificent coffered ceiling, a simple wooden ceiling was installed, the portals were plain wooden doors, the walls were plastered white and an asphalt ceiling had been spread out on the floor. This room was used as an exhibition space until the 1960s. It wasn't until 1957 that the town launched a competition to redesign the space based on the requirements that the space would not only be a reconstruction of the past, but "as before express the character and dignity of the city." 36 designs were submitted, but fortunately none was accepted because they allegedly interfered too much with the existing room structure. It wasn't until 1996 that the Golden Hall was officially returned to the public in its original state.

Just from the train station down Prinzregentstr. is the Landratsamt (District administration office) with the reichsadler still above the door from which only the swastika has been chiseled out, state-protected by a mesh screen. The building dates from May 1938 and was used first as the Reich Railway Directorate, then until 1971 as the Federal Railway Directorate:

The building with an example of a vehicle registration plaque from the Landsrat during the Nazi era. Also on the façade behind me is a Nazi relief typical of the time for the German Workers' Front.

Directly across from the building was the Gestapo headquarters at Prinzregentenplatz 1. After the Nazis took power, the Gestapo merged with the political police, enabling them to obtain information about the Nazis' political opponents in Augsburg. Here within the basement of this impressive building was where interrogations would take place under the control of Gestapo chief Hugo Gold, who was responsible for the mistreatment during the interrogations and was described by everyone who had dealings with him as particularly cruel.

In 1938, the Gestapo moved into an 'aryanised' building at Prinzregentenstraße 11 shown on the right whose Jewish previous owner had to flee to the United States. The cells are still intact but not open to the public; some photos of the walls with prisoners' writing and etchings are found here. Next door at Prinzregentenstraße 9 lived Clara and Martin Cramer. Two of their three childrenwere able to flee to the United States whilst the parents were deported to Piaski in 1942 along with their third child, Erwin,all presumed murdered. Their son Ernst Cramer returned to Germany after the war, became a respected journalist and received the Federal Cross of Merit, becoming an honorary citizen of the city of Augsburg before dying in 2010. In

June 1941, the Augsburg Gestapo office was subordinated to that on Munich's

Hitlerstraße and Gold was transferred to Halle, eventually ending the

war in Italy. After the war, the Amerikahaus was opened at Prinzregentenstraße 11 and today the building houses the Housing Office. Apparently a memorial plaque commemorates Nazi victims but I didn't notice it.

The Augsburg tax office on Peutingerstraße laid out the tax laws in paragraph 1, sentence 1 of its Tax Adjustment Act of October 1934: " The tax laws are interpreted by Nazi ideology." Citizens were asked to list the number of "Aryan" children they had whilst those seen as living outside the community- Jehovah's Witnesses, forced labourers , Sinti and Roma, Jews were targeted. In 1933 there were 126 Jewish-owned enterprises in Augsburg, including 20 of the industry and 55 wholesale companies. Their total number went back to 79 by the reprisals until 1938. In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, on the morning of November 10, 1938, the synagogue built at Halderstraße from 1917 was set on fire. Jewish shops and private apartments were then devastated. The male Jewish fellow citizens were dragged into the concentration camp to force them to emigrate and confiscate their assets through the so-called Arisierung.

The confiscation of Jewish property was initiated from the Alltagsgeschäft but later centralised with the start of the deportations in 1941. In 1985 the synagogue was reopened after a long restoration and was partly used as a Jewish museum.At the Jewish cemetery on Haunstetter Strasse, a memorial stone commemorates the approximately 400 murdered Augsburg victims of the Shoah. In addition to many other resistance fighters such as Bebo Wager, the SPD parliamentary deputy Clemens Högg was also killed during the Nazi period. During the war several external camps of the Dachau concentration camp were erected due to the decentralisation of the armament production of the Messerschmitt AG aircraft factory in Augsburg and the surrounding area. In the district of Kriegshaber there existed a women's camp for 500 Hungarian women in the area of today's Ulmerstrasse. In the district of Haunstetten a men's camp for 2,700 concentration camp prisoners was built in the area of a former gravel pit. After it was destroyed during the wartime bombing, a new men's camp was set up in an air-to-air barracks of Pfersee. Also in Gablingen there was a camp for a thousand prisoners as well as in Horgau. 235 of the prisoners were murdered by ϟϟ men or died of horrific, inhumane conditions and were buried at the Westfriedhof cemetery, where three memorial plaques commemorate them. In the spring of 1945, prisoners were driven out of the barracks of Pfersee to Klimmach in the spring of 1945, with many of them being killed.

.gif) |

| Cleaning up the rubble and today |

The Fuggerhaus on Maximilanstrasse then and now with the building after the war on the right. After 1939 the Nazis wanted to rename Fuggerstrasse to "Strasse des Führers", but this intention was never achieved. Hitler had commissioned Hermann Giesler to deal with the design of Fuggerstrasse, which he did in the years 1939-41 after having submitted his plan for the Gauforum. This would have transformed Fuggerstrasse into a nearly fifty- metre wide parade street involving the destruction of its six-row linden trees and the deep fronted gardens had to disappear. Nazi "tree experts" consequently declared the avenue to be "sick" without further ado. Giesler was able to have the trees cut down in 1939. Nor did he stop at the front gardens and have them removed, although some of these front gardens housed cafes . Only the outer row of avenues was planted with new linden trees which still stretch along Fuggerstrasse today.

The Fuggerei - the world's oldest social housing complex still in use. The Fuggerei was donated on August 23, 1521 by Jakob Fugger as a residential settlement for needy citizens of Augsburg and built between 1516 and 1523 under the supervision of the architect Thomas Krebs. At that time, 52 apartments were built around the first six streets according to largely standardised layouts in the two-storey buildings passing through were generously planned for the conditions of the period of development. The concept of the Fuggerei was a very modern concept for self-help, intended for those who were threatened with poverty and who were day workers who could not manage their own household, for reasons such as disease. They were able to pursue their bread-making businesses and able to leave in the event of economic recovery. Until the twentieth century, Fuggerei was usually home to families with several children. Only "worthy arms" were allowed to enter the social settlement as beggars were not accepted according to the will of the founder. During the Thirty Years' War the Fuggerei was largely destroyed by the Swedes until 1642. From 1681 until his death in 1694 Franz Mozart, the great-grandfather of the composer, lived in the Fuggerei which a plaque inside commemorates. Extensions of the Fuggerei took place in the years 1880 and 1938. During the war, the settlement was destroyed by a British air raid attack during the so-called Augsburger Bombennacht of February 25-26, 1944. Already by March 1, 1944, the Fürstlich and Gräflich Fuggersche family senate decided in writing to rebuild the Fuggerei. From 1945 onwards the social settlement was rebuilt according to the plans of Raimund von Doblhoff by means of the foundation, so that in 1947 the first buildings could be reused. In the 1950s reconstruction was completed. Until 1973, the Fuggerei was extended to a total of 67 houses with 140 apartments on additional adjacent ruins.

Nazi reliefs still adorning façades

Theodor Wiedemann Strasse 35 still has two Nazi reliefs- the one on the left shows a relief representing a link between the Roman Empire and the Third Reich whilst the right shows a tank and the warship below a representation of the air force bombing from above and the German army all within the ægis of the Nazi eagle. The tank and lightning are aligned towards the east whilst the eagle directs its gaze towards France.  The

relief found at Firnhaberstrasse 53 at the bottom-right shows a

stylised representation of a Messerschmidt BF 109 - the most important

fighter of the Luftwaffe.

The

relief found at Firnhaberstrasse 53 at the bottom-right shows a

stylised representation of a Messerschmidt BF 109 - the most important

fighter of the Luftwaffe.

According to 'Taff' Simon of Dark History Tours here in Munich during one of his archaeological digs in Augsburg,

The

relief found at Firnhaberstrasse 53 at the bottom-right shows a

stylised representation of a Messerschmidt BF 109 - the most important

fighter of the Luftwaffe.

The

relief found at Firnhaberstrasse 53 at the bottom-right shows a

stylised representation of a Messerschmidt BF 109 - the most important

fighter of the Luftwaffe. According to 'Taff' Simon of Dark History Tours here in Munich during one of his archaeological digs in Augsburg,

this spot is not ten minutes walk away. I'll go back and finish taking photos with a full battery. In retrospect I should have asked the old boy if he had an air raid shelter for a basement. On my walk up, I spotted an escape hatch in a hedge - this would go under the Kleingarten, and theoretically could be associated with the BDM/HJ apartments.

These residential buildings located in the Hochfeld district were built for the workers of the Bavarian Aircraft Works (later Messerschmitt Works) due to the need in the armaments industry. Such reliefs loyal to the Nazi party line were placed above the house entrances or on house walls to express the higher culture and overall superiority of the Aryan race. This particular relief dated 1935 on the left located at Agnes Bernauer-Strasse 46 shows the typical representation of the idealised Nazi family as represented in Adolf Wissel's Kahlenberger Bauernfamilie with the boy looking straight ahead representing the future of the Aryan race. The father's role is to protect his family and prepare his son for the future and therefore is portrayed as the head of the family, supervising and protecting his children. The mother serves to procreate to guarantee the descendants of her family and the future of the herrenvölk, to take care and protect them, but also to guarantee the tasks destined for the family.

Above the doors at Richthofen Strasse are reliefs representing the Deutschen Arbeitsfront, Hitlerjugend and the NS Frauenschaft; only the swastikas have been removed from the devices.

The huge Nazi eagle overlooking Reinöhlstrasse, recently repainted as seen on the GIF on the right taken during visits over several years

Reliefs celebrating the 1936 Olympic Games at Gentnerstrasse 53-59; note the Hitler hairstyle in the relief on the bottom-right.

I hadn't heard of this 'Augsburg Liberation Movement' which consisted of about a dozen men which helped the American 3rd Infantry Division 'liberate' the town from the Germans (apparently only after it became clear the war was days from being lost) until I came across this plaque. Google-searching the group in English found only one entry for it. When the 7th American Infantry Division approached Wertingen Augsburg from the west, they distributed leaflets telling the people to hoist white flags. "Save your old town and its inhabitants from the rain of steel that threatens Augsburg with destruction." City Commander General Fehn had 800 more men available and refused to surrender, building barricades on bridges and underpasses. Wertach and Lech bridges were to have been blown up but mayor Mayr did not give the order for the prepared blasts. The resistance group around Dr. Rudolf Lang, a senior physician at the main hospital in Augsburg, had prepared the delivery of the city through negotiations with the Gauleiter, Mayr and General Fehn and then made contact with the Americans.

Franz Hesse had cycled to Westheim and had agreed to the transfer; by the morning he led a number of tanks and jeeps into the city to the command bunker in Riedingerhaus on the hauptstrasse where the Stadtwerkehaus is. In front of the Riedingerhaus, other members of the Freiheitsaktion were waiting. A small troop of American soldiers entered the bunker, gave Fehn an ultimatum that passed, and arrested him and Mayr thus ending Augsburg's war on the morning of April 28th. The American Combat report of the day honours the initiatives of the Freedom Action, whose role Wahl played down after the war in order to make his more luminous. "Augsburg was largely preserved from the complete destruction that came from Aschaffenburg, Würzburg, Heilbronn, Nuremberg and Ulm thanks to a unique revolutionary movement that greatly facilitated the invasion of American troops."

|

| The Annahof in 1930 |

After the war Adolf-Hitler-Platz was renamed Königsplatz again; Benito-Mussolini-Platz became Kaiserplatz; Braunauer Strasse became Kolbergstrasse whilst Braunauer Platz became Nettelbeck-Platz and Brucknerstrasse was changed to Mendelsohn-Strasse. Schools were also renamed with Horst Wessel School now Hammerschmiedschule, Hans Schemm School becoming the Hall School and Andreas Weit School became a butcher's school.

Standing outside the synagogue. In

1933 there were 1,033 Jews living in Augsburg comprising 0.6% of the

176 000 inhabitants. About 175 companies in the town had Jewish owners. On a plaque in the synagogue are the names of twenty four "sons of the community" who died in the Great War for their country. In 1913 the local Jewish community had the architects Lömpel and Landauer built this synagogue in the town centre which was dedicated in 1917. Described as "possibly the most significant art nouveau synagogue in Europe" it was seriously damaged during Kristallnacht but survived before finally reopening in 1985. From the start of the Nazi era Jews were targetted- among the 600 first arrested in those opening months included four Jewish lawyers placed in "protective custody", probably because they had many Social Democrats among their clients including Dr. Ludwig Dreyfuss who had been mayor of Augsburg. Others arrested were Dr. Julius Nördlinger; Guido Nora, the secretary-general of the city theatre; and Max Gift, the the managing director of the department store Landauer and brother of the actress Therese Giese. From her we know that he fled to South America where he died.

Standing outside the synagogue. In

1933 there were 1,033 Jews living in Augsburg comprising 0.6% of the