Arles

After barbarians from northern Europe defeated the Roman armies at the Battle of Arausio (today's Orange) in 105 BCE, Consul Marius intervened in the region of Arles where, for logistical reasons, he had a wide ditch dug called Fosses Mariennes at the mouth of the Rhône before crushing the barbarians. After his subsequent victories, Marius abandoned the use of the new waterway to the Marseillais who thus extended their influence to Arles, now a port for both river and sea. As a reward for supporting Marius's nephew Julius Caesar against Marseille in 49 BCE during the civil war. Caesar records his approach to the city which he designates by Arelate in the Bello Civico I.36.4: "Naves longas Arelate number XII facere institute (He had twelve warships built in Arles)." These vessels, built in less than a month, allowed him to win his battle against Marseilles on June 12, 49 BCE. To reward Arles for this help, he instructed Tiberius Claudius Nero , father of the future emperor Tiberius, to found the Roman colony of Arelate in the autumn of 45 BCE for

men of the 6th Legion, and this was reflected in the colony’s official

name: Colonia Julia Paterna Arelatensum Sextanorum, or Julius’ Paternal

Colony of the Sixth at Arelate. The settlers of this new province were given territory taken from that of Marseilles. The first governor of Arelate was Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus.

After barbarians from northern Europe defeated the Roman armies at the Battle of Arausio (today's Orange) in 105 BCE, Consul Marius intervened in the region of Arles where, for logistical reasons, he had a wide ditch dug called Fosses Mariennes at the mouth of the Rhône before crushing the barbarians. After his subsequent victories, Marius abandoned the use of the new waterway to the Marseillais who thus extended their influence to Arles, now a port for both river and sea. As a reward for supporting Marius's nephew Julius Caesar against Marseille in 49 BCE during the civil war. Caesar records his approach to the city which he designates by Arelate in the Bello Civico I.36.4: "Naves longas Arelate number XII facere institute (He had twelve warships built in Arles)." These vessels, built in less than a month, allowed him to win his battle against Marseilles on June 12, 49 BCE. To reward Arles for this help, he instructed Tiberius Claudius Nero , father of the future emperor Tiberius, to found the Roman colony of Arelate in the autumn of 45 BCE for

men of the 6th Legion, and this was reflected in the colony’s official

name: Colonia Julia Paterna Arelatensum Sextanorum, or Julius’ Paternal

Colony of the Sixth at Arelate. The settlers of this new province were given territory taken from that of Marseilles. The first governor of Arelate was Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus.  Upon Caesar's assassination his nephew and adopted son, the future emperor Augustus, renamed the colony Colonia Julia Paterna Arelate Sextanorum, and visited the town himself around 40 BCE to organise this bastion of Roman power which then imposed itself against its rival Marseille. With the creation of the colony, the people of Arles, freed from the tutelage of Marseilles, became true Roman citizens with the possibility of taking part in the deliberations of the people in the assemblies of the capital when they went there. As such, the Arlesians were registered as one of the tribes of Rome, the Teretina tribe.

Upon Caesar's assassination his nephew and adopted son, the future emperor Augustus, renamed the colony Colonia Julia Paterna Arelate Sextanorum, and visited the town himself around 40 BCE to organise this bastion of Roman power which then imposed itself against its rival Marseille. With the creation of the colony, the people of Arles, freed from the tutelage of Marseilles, became true Roman citizens with the possibility of taking part in the deliberations of the people in the assemblies of the capital when they went there. As such, the Arlesians were registered as one of the tribes of Rome, the Teretina tribe. Arelate was an important city in Roman times, of which it has preserved many vestiges, in particular the arenas and the necropolis of Alyscamps. Strabo in 18 AD referred to the commercial role of the city, and a little later Pliny the Elder mentioned Arelate Sextanorum. From the beginning of the century a Roman road, the via Agrippa, linked the city to Vienne and Lyon. Benefiting for more than five centuries from a strategic geopolitical situation on the Rhône, from successive urban plans and the support of several emperors, it became one of the first Christian centres of Gaul and imperial residence and then, at the end of the 4th century, a praetorian prefecture. Besieged in 425, 430, 453, 457 and 471 , the city was finally taken by the Visigoth king Euric for the first time in 472 and then definitively in 476.

During the Second World War Arles became the victim of five aerial bombings in the summer of 1944 in which the city lost its station, its two bridges and 28% of its habitat. Also destroyed were two churches, Saint-Julien and Saint-Pierre-de-Trinquetaille, whilst the amphitheatre, the ramparts and Notre-Dame-de-la-Major werev rendered seriously damaged

.gif) The

Roman amphitheatre in Arles in the 19th century and in 2015 with Drake

Winston two years after the completion of the restoration campaign led

by Alain-Charles Perrot, Chief Architect of Historic Monuments. Nearly 25 million euros were devoted to

this restoration which lasted ten years and which was, at that time,

one of the largest sites on Heritage in France. The amphitheatre itself

was built around 80 -90 by the orders of the Emperor Domitian as part of

the Flavian extensions of the city. The amphitheatre of Arles is the

most important monument of the ancient Roman colony that remains some

two millennia after its construction. Roman engineers had to build the

amphitheatre of on the hill of Hauture; to do this, they had to first

demolish the Augustan enclosure erected a century earlier. The arena

takes up the classic characteristics of this type of construction and

was inspired by the Colosseum in Rome which had just been completed.

Like it, an evacuation system via numerous access corridors, an

elliptical central stage surrounded by bleachers, arcades over two

levels for a total length of 136 metres. At each level, a circular

gallery gave access to the bleachers by stairs alternating with vertical

passages. The building could accommodate 25,000 spectators. In 255 the

Emperor Gallus had games organised here in celebration of the victories

won by his armies in Gaul. At the beginning of the 4th century ,

Constantine had great hunts and battles depicted there on the occasion

of the birth of his eldest son. Later, Majoran gave several shows there.

Finally, we know from Procopius that in 539 Childebert, king of Paris,

having visited the south of Gaul, wanted the games of the ancients to be

renewed in his presence. By the end of the 6th century however, the

arena had to adapt to the return of insecurity to transform itself into a

bastide , a sort of urban fortress which, over time, had four towers

and in which are integrated more than two hundred dwellings and two

chapels.

The

Roman amphitheatre in Arles in the 19th century and in 2015 with Drake

Winston two years after the completion of the restoration campaign led

by Alain-Charles Perrot, Chief Architect of Historic Monuments. Nearly 25 million euros were devoted to

this restoration which lasted ten years and which was, at that time,

one of the largest sites on Heritage in France. The amphitheatre itself

was built around 80 -90 by the orders of the Emperor Domitian as part of

the Flavian extensions of the city. The amphitheatre of Arles is the

most important monument of the ancient Roman colony that remains some

two millennia after its construction. Roman engineers had to build the

amphitheatre of on the hill of Hauture; to do this, they had to first

demolish the Augustan enclosure erected a century earlier. The arena

takes up the classic characteristics of this type of construction and

was inspired by the Colosseum in Rome which had just been completed.

Like it, an evacuation system via numerous access corridors, an

elliptical central stage surrounded by bleachers, arcades over two

levels for a total length of 136 metres. At each level, a circular

gallery gave access to the bleachers by stairs alternating with vertical

passages. The building could accommodate 25,000 spectators. In 255 the

Emperor Gallus had games organised here in celebration of the victories

won by his armies in Gaul. At the beginning of the 4th century ,

Constantine had great hunts and battles depicted there on the occasion

of the birth of his eldest son. Later, Majoran gave several shows there.

Finally, we know from Procopius that in 539 Childebert, king of Paris,

having visited the south of Gaul, wanted the games of the ancients to be

renewed in his presence. By the end of the 6th century however, the

arena had to adapt to the return of insecurity to transform itself into a

bastide , a sort of urban fortress which, over time, had four towers

and in which are integrated more than two hundred dwellings and two

chapels. The doctor and geographer Jérome Münzer passing through Arles in 1495 wrote of how

“poor people live in this theatre, having their huts in the hangers and

on the arena." King François I, visiting the city in 1516, expressed

surprise and regret to find such a building in such a sad state. This

residential function was perpetuated over time before the expropriation

started at the end of the 18th century was finally completed in 1825 at

the instigation of the mayor at the time, Baron de Chartrouse . The

arena rediscovered its original function in 1830, during an inaugural

party on the occasion of the celebration of the taking of Algiers, with

the bullfighting show which earned it its current common name of Arènes.

It took another decade on December 30 , 1840 that the Archaeological

Commission demolished the last houses backing onto the amphitheatre.

Today it hosts many shows, bullfights , Camargue races (including the

golden cockade), theatrical performances and musical performances as a

way of combining the preservation of ancient heritage and the cultural

life of today. Summer sees a return to basics for the amphitheatre when

every Tuesday and Thursday, a team of professionals brings Roman customs

and customs to life, presenting gladiator fights to the public.

German

forces occupied Arles when they took over all of France including its

"free zone" administered by the Vichy Government in November 1942 as a

precaution when the allies invaded North Africa. Within the months

before the allied landing in Southern France in August 1944 a large

number of bombing raids were carried out by the allies in order to

destroy railway lines and stations and cut the bridges across the Rhone

to hinder the German retreat. Arles had endured eight raids between 25

June and 15 August which inflicted great damage to the buildings and a

considerable number of civilian deaths. Van Gogh's Maison Jaune

was destroyed (see below) as most of the bridges along the Rhone were

bombed. The bombing was actually carried out by groups from the Free

French Airforce - thus ironically by Frenchmen themselves - flying

American B26 Marauder medium bombers. As the Germans retreated up the

west bank of the Rhone this had been quite unnecessary.

German

forces occupied Arles when they took over all of France including its

"free zone" administered by the Vichy Government in November 1942 as a

precaution when the allies invaded North Africa. Within the months

before the allied landing in Southern France in August 1944 a large

number of bombing raids were carried out by the allies in order to

destroy railway lines and stations and cut the bridges across the Rhone

to hinder the German retreat. Arles had endured eight raids between 25

June and 15 August which inflicted great damage to the buildings and a

considerable number of civilian deaths. Van Gogh's Maison Jaune

was destroyed (see below) as most of the bridges along the Rhone were

bombed. The bombing was actually carried out by groups from the Free

French Airforce - thus ironically by Frenchmen themselves - flying

American B26 Marauder medium bombers. As the Germans retreated up the

west bank of the Rhone this had been quite unnecessary.The bridge was built in 1868 to allow trains of the PLM company [Paris-Lyon Marseille] to link Arles to Lunel cross the Rhone river, which is already quite wide at this point. This line in particular was dedicated to dispatch the coal produced in the Cevennes mountains. The bridge was destroyed on the 6th of August 1944, during a bombing. All that remains of the bridge are its pillars and imposing sculptured lions. The lion sculptures are the work of Pierre Louis Rouillard.

The pillars remain standing. The arrival of German troops in Arles brought immediate changes to the town's administrative and social landscape. Contrary to the notion that the occupation was merely an imposition of German rule, Paxton asserts that Vichy France was a willing collaborator. This complicates the situation in Arles, as it was a place caught between two regimes. Both the Nazis and the Vichy government sought to exert influence, and their interests often converged. For example, stringent anti-Semitic laws were quickly enacted, affecting the town’s Jewish population profoundly. Property was seized, and individuals were rounded up for deportation, mirroring the broader Holocaust policies implemented across Europe. Concurrently, the imposition of a strict curfew and other civil restrictions created a stifling atmosphere that deeply impacted everyday life. Economically, the occupation years were a period of scarcity and hardship for Arles. The Germans requisitioned a significant portion of the town’s resources, from food to machinery, contributing to a dire situation that was exacerbated by the absence of many men who had either fled or been conscripted. Vinen argues that this contributed to a ‘shadow economy’, where black markets and informal trading became prevalent as people sought to survive. Even though this alternative economy offered some relief, it also led to a dramatic increase in crime rates and corruption, complicating the moral landscape of the town.

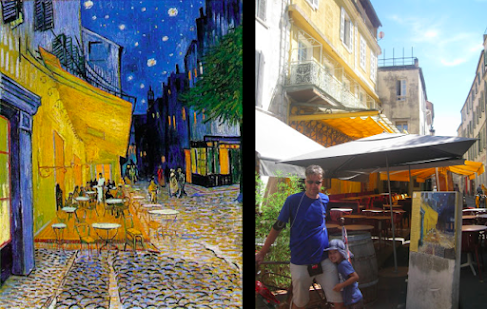

Van Gogh's Trinquetaille Bridge of 1888, since replaced after being bombed during the war- note the tree in both. Both bridges that linked the Trinquetaille district to Arles were destroyed respectively on August 6, 1944 and August 15, 1944 by Allied bombing, which completely isolated the district from the rest of the city. The area itself was bombed the war with the main destruction suffered in Arles occurred in 1944 by six Allied bombardments during the fighting for the liberation of Provence. The objectives were the destruction of the bridges, but several districts, notably La Roquette, La Cavalerie and Trinquetaille, were damaged. Trinquetaille alone saw 405 buildings destroyed, involving over a thousand homes with only the bell tower of the Saint-Pierre church still standing. In June of 1987, this painting sold for $20.2 million making it the second highest price ever paid for a painting at auction. Living

in Arles, he was at the height of his career, producing some of his

best work: sunflowers, fields, farmhouses and people of the Arles, Nîmes

and Avignon areas. In less than

fifteen months he had produced about an hundred drawings, produced more than 200

paintings and wrote more than 200 letters. The canals, drawbridges,

windmills, thatched cottages and expansive fields of the Arles

countryside reminded Van Gogh of his life in the Netherlands. Arles

brought him the solace and bright sun that he sought for himself and

conditions to explore painting with more vivid colours, intense colour

contrasts and varied brushstrokes. He also returned to the roots of his

artistic training from the Netherlands, most notably with the use of a

reed pen for his drawings.

Van Gogh's Trinquetaille Bridge of 1888, since replaced after being bombed during the war- note the tree in both. Both bridges that linked the Trinquetaille district to Arles were destroyed respectively on August 6, 1944 and August 15, 1944 by Allied bombing, which completely isolated the district from the rest of the city. The area itself was bombed the war with the main destruction suffered in Arles occurred in 1944 by six Allied bombardments during the fighting for the liberation of Provence. The objectives were the destruction of the bridges, but several districts, notably La Roquette, La Cavalerie and Trinquetaille, were damaged. Trinquetaille alone saw 405 buildings destroyed, involving over a thousand homes with only the bell tower of the Saint-Pierre church still standing. In June of 1987, this painting sold for $20.2 million making it the second highest price ever paid for a painting at auction. Living

in Arles, he was at the height of his career, producing some of his

best work: sunflowers, fields, farmhouses and people of the Arles, Nîmes

and Avignon areas. In less than

fifteen months he had produced about an hundred drawings, produced more than 200

paintings and wrote more than 200 letters. The canals, drawbridges,

windmills, thatched cottages and expansive fields of the Arles

countryside reminded Van Gogh of his life in the Netherlands. Arles

brought him the solace and bright sun that he sought for himself and

conditions to explore painting with more vivid colours, intense colour

contrasts and varied brushstrokes. He also returned to the roots of his

artistic training from the Netherlands, most notably with the use of a

reed pen for his drawings.

In front of the Langlois Bridge at Arles, the subject of four oil paintings, one watercolour and four drawings by Vincent van Gogh. The works, made in 1888 when Van Gogh lived in Arles, represent a melding of formal and creative aspects. Van Gogh used a perspective frame that he built and used in The Hague to create precise lines and angles when portraying perspective.Van Gogh was influenced by Japanese woodcut prints, as evidenced by his simplified use of colour to create a harmonious and unified image. Contrasting colours, such as blue and yellow, were used to bring a vibrancy to the works. He painted with an impasto, or thickly applied paint, using colour to depict the reflection of light. The subject matter, a drawbridge on a canal, reminded him of his homeland in the Netherlands. He asked his brother Theo to frame and send one of the paintings to an art dealer in the Netherlands. The reconstructed Langlois Bridge is now named Pont Van-Gogh.

Van Gogh had been 35 when he made the Langlois Bridge paintings and drawings. The Langlois Bridge was one of the crossings over the Arles to Bouc canal. It was built in the first half of the 19th century to expand the network of canals to the Mediterranean Sea. Locks and bridges were built, too, to manage water and road traffic.

Just

outside Arles, the first bridge was the officially titled "Pont de

Réginel" but better known by the keeper's name as "Pont de Langlois". In

1930, the original drawbridge was replaced by a reinforced concrete

structure which, in 1944, was blown up by the retreating Germans who

destroyed all the other bridges along the canal except for the one at

Fos-sur-Mer, a port on the Mediterranean Sea. The Fos Bridge was

dismantled in 1959 with a view to relocating it on the site of the

Langlois Bridge but as a result of structural difficulties, it was

finally reassembled at Montcalde Lock several kilometres away from the

original site. According to letters to his brother Theo, Van Gogh began a

study of women washing clothes near the Langlois Bridge about mid-March

1888 and was working on another painting of the bridge about April 2.

This was the first of several versions he painted of the Langlois Bridge

that crossed the Arles canal. Reflecting on Van Gogh's works of the Langlois Bridge Debora Silverman, author of the book Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art comments, "Van Gogh's depictions of the bridge have been considered a quaint exercise in nostalgia mingled with Japonist allusions." Van Gogh

approached the making of the paintings and drawings about the bridge in

a "serious and sustained manner" with attention to "the structure,

function, and component parts of this craft mechanism in the landscape."

The Maison Jaune,

also the subject of Van Gogh, didn't survive the bombing and no longer

exists. The place without the house looks almost the same. Although Van

Gogh's building is gone a placard on the scene commemorates its former

existence.

Marshal

Petain and Admiral Darlan in front of the Town Hall with Petain's

portrait on the façade when France was fighting the British and

Americans in North Africa. By 1945 they had switched sides and Petain

had been replaced with the portraits of Churchill, FDR, Stalin and,

protecting national sensibilities, de Gaulle.At the Barbegal aqueduct and mill, a Roman watermill complex located near Arles, described as "the greatest known concentration of mechanical power in the ancient world." It was built to supply drinking water from the mountain chain of the Alpilles to Arelate on the Rhône River. Within ten miles north of Arles at Barbegal, near Fontvieille, where the aqueduct arrived at a steep hill, the aqueduct fed two parallel sets of eight water wheels to power a flourmill. There are two aqueducts which join just north of the mill complex, and a sluice which enabled the operators to control the water supply to the complex. The mill consisted of 16 waterwheels in two separate descending rows built into a steep hillside. There are substantial masonry remains of the water channels and foundations of the individual mills, together with a staircase rising up the hill upon which the mills are built. The mills apparently operated from the end of the 1st century until about the end of the 3rd century. Described as the world's oldest biscuit factory, scientists now believe the enormous Roman Barbegal factory was used to mass-produce snacks to feed second century sailors during long voyages at sea.

Father and son's photo of mom between arches

Chapel of Saint-Gabriel de Tarascon

At the Chapel of Saint-Gabriel de Tarascon, a Romanesque chapel located southeast of Tarascon. It was built in the

third quarter of the 12th century and constitutes one of the finest

examples of Provençal Romanesque art inspired by antiquity, decorated with biblical

scenes including above the door Adam and Eve and the snake curling

around the tree of knowledge of good and evil, along with Daniel with

lions. It's surprising that this church of such great architectural quality is located away from Tarascon without being able to attach to the monument any pilgrimage that could justify it. In fact, the place was in Roman times at the meeting point of two important branches of the Via Herculea, the name given to a mythical road that lead from the Strait of Gibraltar in Spain to the Col de Montgenèvre in the Alps, crossing the Pyrenees, skirting the Mediterranean coast and passing through Narbo (Narbonne). and Nemausus (Nîmes ). This route was replaced in Roman times by the Via Domitia and the Via Augusta. Archaeological research around the chapel has brought to light the foundations of houses which have shown the extent of the ancient settlement, making it possible to find an early Christian cemetery which allows us to affirm that these activities did not disappear with the barbarian invasions.The chapel itself has suffered numerous kinds of violence

passing the centuries, including bombing by the Allies during the Second

World War.

Orange

On October 6 105 BCE

the Battle of Orange took place. The Teutons, allied with the Cimbri,

the Ambrones and the Helvetii crushed the Roman legions of the consul

Gnaeus Mallius Maximus and of Quintus Servilius Caepio in front of

Arausio. The treasure of the Volques, which they had pillaged at

Toulouse , was thrown into the Rhône by the victors. The historian

Orosius wrote:"They threw into the river gold, silver, weapons,

cuirasses, vases even after having broken them, the clothes of the

corpses were lacerated and the horses still alive were thrown into an

abyss". Provencia and the road to Rome were open to them, but the

coalition split to move towards Spain or go up towards Gaul. Many think

that the gold from the Volques de Toulouse, thrown into the Rhône by the

Cimbri, is still at the bottom of the river.

At the triumphal arch of Orange, a Roman monumental arch from the beginning of the 1st century, which marked the northern entrance to Arausio (today hui Orange) on the Via Agrippa- the national road 7 before its decommissioning. It was possibly erected during the reign of

Augustus between the years 20 and 25 to honour the

veterans of the Gallic Wars and Legio II Augusta. It was later

reconstructed by emperor Tiberius to celebrate the victories of

Germanicus over the German tribes in Rhineland. The arch contains an

inscription dedicated to emperor Tiberius in 27. The arch is

decorated with various reliefs of military themes, including naval

battles, spoils of war and Romans battling Germans and Gauls. Almost all the surfaces of the arch are covered with reliefs, among which representations of weapons and tropaia predominate. A Roman

foot soldier carrying the shield of Legio II Augusta is seen on the

north front battle relief for example. There are also battle reliefs of victorious Romans fighting defeated Gauls, as well as subordinate reliefs from the field of Roman religion . Fixing holes for the attachment of metal letters, which approximately determine the occasion and time of the construction of the building, allow the inscription to be reconstructed, even if its interpretation is disputed.

In the Middle Ages, the monument was fortified to serve as an advanced bastion at the entrance to the city. The arch was converted into a fortress in the 13th century and fitted with an eight metre high tower. It was then owned by Raymond I des Baux, the prince d'Orange, and belonged to the Principality of Orange until 1725 .

.gif) How the arch appears from Hubert Robert's 1789 painting The Ruins of Nîmes, Orange and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence showing the dilapidated state of the arch and how much today is a product of extensive restoration. The seemingly good state of preservation of the arch, which to the layman appears to be largely intact evidence of ancient architecture, is thus the result of over 200 years of restoration and renewal. As early as 1721, a prince de Conti, probably Louis Armand II de Bourbon had the tower erected on the arch in the 13th century demolished. In 1725, the pilasters in the western and central passages and the western archivolt of the south side were renewed, as was the left half-column of the south side. In order to secure the building, the upper part of the west side was bricked up in 1772. In 1808 Alexandre Reux, departmental architect of Vaucluse, carried out safety and conservation work on the arch. As part of this work, the pilasters, impost capitals and archivolts of the western passage on the south side were added, and the south-east corner was completely restored. In addition, the pilasters on the north side were added and the extensions leaning against the western facade were demolished. When the Route Nationale 7 was expanded in 1809, a square was created with the arch in the middle, around which the road ran on both sides.

How the arch appears from Hubert Robert's 1789 painting The Ruins of Nîmes, Orange and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence showing the dilapidated state of the arch and how much today is a product of extensive restoration. The seemingly good state of preservation of the arch, which to the layman appears to be largely intact evidence of ancient architecture, is thus the result of over 200 years of restoration and renewal. As early as 1721, a prince de Conti, probably Louis Armand II de Bourbon had the tower erected on the arch in the 13th century demolished. In 1725, the pilasters in the western and central passages and the western archivolt of the south side were renewed, as was the left half-column of the south side. In order to secure the building, the upper part of the west side was bricked up in 1772. In 1808 Alexandre Reux, departmental architect of Vaucluse, carried out safety and conservation work on the arch. As part of this work, the pilasters, impost capitals and archivolts of the western passage on the south side were added, and the south-east corner was completely restored. In addition, the pilasters on the north side were added and the extensions leaning against the western facade were demolished. When the Route Nationale 7 was expanded in 1809, a square was created with the arch in the middle, around which the road ran on both sides. A later view of the arch can be seen on the right from Victor Cassien and Alexandre Debelle's Album du Dauphiné, from 1839. The arch was further restored in the 1820s by the architect Auguste Caristie

who began by clearing the buttresses and medieval additions, before

proceeding to a non-aggressive reconstruction of the monument, replacing

the unusable parts or missing in an identifiable way; the entire west side of the arch, which was badly damaged, was completely redesigned using only two antique components. The additions to the north side included the corner columns, parts of the weapon relief located above the western passage, the corner pilasters of the lower attic and the western pedestal of the upper attic. .gif) On the badly damaged south side, he had the western semi-columns and all profiles renewed. With the exception of the east side, which is still best preserved, the entire entablature on the arch above the blind columns was renewed. Caristie made sure that the additions and renewals were identified as such and did not elaborate on the ornamentation. This downright modern approach to monument preservation was discarded during the restorations between 1950 and 1957. Now the additions, which can be recognised as modern, were subsequently ornamented and artificially weathered by means of sandblasting. Since then, it has hardly been possible to distinguish between the antique inventory and the modern additions.

On the badly damaged south side, he had the western semi-columns and all profiles renewed. With the exception of the east side, which is still best preserved, the entire entablature on the arch above the blind columns was renewed. Caristie made sure that the additions and renewals were identified as such and did not elaborate on the ornamentation. This downright modern approach to monument preservation was discarded during the restorations between 1950 and 1957. Now the additions, which can be recognised as modern, were subsequently ornamented and artificially weathered by means of sandblasting. Since then, it has hardly been possible to distinguish between the antique inventory and the modern additions.

.gif) On the badly damaged south side, he had the western semi-columns and all profiles renewed. With the exception of the east side, which is still best preserved, the entire entablature on the arch above the blind columns was renewed. Caristie made sure that the additions and renewals were identified as such and did not elaborate on the ornamentation. This downright modern approach to monument preservation was discarded during the restorations between 1950 and 1957. Now the additions, which can be recognised as modern, were subsequently ornamented and artificially weathered by means of sandblasting. Since then, it has hardly been possible to distinguish between the antique inventory and the modern additions.

On the badly damaged south side, he had the western semi-columns and all profiles renewed. With the exception of the east side, which is still best preserved, the entire entablature on the arch above the blind columns was renewed. Caristie made sure that the additions and renewals were identified as such and did not elaborate on the ornamentation. This downright modern approach to monument preservation was discarded during the restorations between 1950 and 1957. Now the additions, which can be recognised as modern, were subsequently ornamented and artificially weathered by means of sandblasting. Since then, it has hardly been possible to distinguish between the antique inventory and the modern additions. The last cleanup of the arch was completed in June 2021; from 2015 to 2017, drainage works made it possible to clean up the bottom of the arch, at the level of which rainwater sometimes stagnated. Trees have since been felled and the road redeveloped, so that vehicles pass less closely. On this occasion, adjustable lighting was installed, making it possible to engage in the current fad of illuminate the arch in different colours, in particular those of the French flag.

The

ancient Roman theatre in Orange was built early in the 1st century AD.

It is one of the best preserved of all the Roman theatres in the Roman

colony of Arausio (or, more specifically, Colonia Julia Firma

Secundanorum Arausio: "the Julian colony of Arausio established by the soldiers of the second legion") which was founded in 40 BCE. Playing a

major role in the life of the citizens, who spent a large part of their

free time there, the theatre was seen by the Roman authorities not only

as a means of spreading Roman culture to the colonies, but also as a way

of distracting them from all political activities. Mime, pantomime,

poetry readings and the farce was the dominant form of entertainment, much of

which lasted all day. Magnificent stage sets became very important, as

was the use of stage machinery, to keep commoners entertained. The entertainment offered was open to

all and free of charge. As the Western Roman Empire declined during the

4th century, by which time Christianity had become the official

religion, the theatre was closed by official edict in 391 CE since the

Church opposed what it regarded as uncivilised spectacles. After that,

the theatre was abandoned completely. It was sacked and pillaged by the barbarians and was used as a defensive post in the Middle Ages.

The

ancient Roman theatre in Orange was built early in the 1st century AD.

It is one of the best preserved of all the Roman theatres in the Roman

colony of Arausio (or, more specifically, Colonia Julia Firma

Secundanorum Arausio: "the Julian colony of Arausio established by the soldiers of the second legion") which was founded in 40 BCE. Playing a

major role in the life of the citizens, who spent a large part of their

free time there, the theatre was seen by the Roman authorities not only

as a means of spreading Roman culture to the colonies, but also as a way

of distracting them from all political activities. Mime, pantomime,

poetry readings and the farce was the dominant form of entertainment, much of

which lasted all day. Magnificent stage sets became very important, as

was the use of stage machinery, to keep commoners entertained. The entertainment offered was open to

all and free of charge. As the Western Roman Empire declined during the

4th century, by which time Christianity had become the official

religion, the theatre was closed by official edict in 391 CE since the

Church opposed what it regarded as uncivilised spectacles. After that,

the theatre was abandoned completely. It was sacked and pillaged by the barbarians and was used as a defensive post in the Middle Ages. The theatre as it appeared and today

Nîmes

The foundation of Nîmes goes back to antiquity with Strabo and Pliny writing of a Celtic tribe would have settled in the region and would have founded, on the territory of the city of Nîmes, the ancient capital of the Volques Arécomiques. The victory won over the Arverni by Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Quintus Fabius Maximus, in 121 BCE, decided the fate of the city. Indeed, the anxiety caused them by their turbulent neighbours induced the Volci to offer themselves to the Romans and place themselves under their protection. This did not, however, allow them to escape the devastation caused by the irruption of the Cimbri and the Teutons. The colony founded by Octavian Augustus under the direction of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa was only definitively organised in the year 27 BCE. The Colonia Augusta Nemausus was endowed with numerous monuments and an enclosure about five miles in length, enclosing the third urban area of the Gauls (provinces of Germania included) over 220 hectares.  The development of the city of Nîmes further intensified due to its geographical location, since the city was crossed by the via Domitia and the Heraclean way. The via Domitia would become essential in the economic development of the city since its led from Italy to the Iberian peninsula. During the 1st century BCE Nîmes gradually broke away from the influence of Marseilles to gradually enter into the orbit of Rome. After the conquest of Marseilles by Caesar, the Romanisation of Nîmes accelerated further with the city then receiving the title of Colonia Augusta Nemausus, allowing the city to keep a certain autonomy without the Romanisation being slowed down. Architecturally, the city took on an increasingly Roman form with an important appearance of several buildings of a public nature. Similarly, dwellings are shifting more and more from the hills to the plain which became a true symbol of the urban expansion of Nîmes.

The development of the city of Nîmes further intensified due to its geographical location, since the city was crossed by the via Domitia and the Heraclean way. The via Domitia would become essential in the economic development of the city since its led from Italy to the Iberian peninsula. During the 1st century BCE Nîmes gradually broke away from the influence of Marseilles to gradually enter into the orbit of Rome. After the conquest of Marseilles by Caesar, the Romanisation of Nîmes accelerated further with the city then receiving the title of Colonia Augusta Nemausus, allowing the city to keep a certain autonomy without the Romanisation being slowed down. Architecturally, the city took on an increasingly Roman form with an important appearance of several buildings of a public nature. Similarly, dwellings are shifting more and more from the hills to the plain which became a true symbol of the urban expansion of Nîmes.

The development of the city of Nîmes further intensified due to its geographical location, since the city was crossed by the via Domitia and the Heraclean way. The via Domitia would become essential in the economic development of the city since its led from Italy to the Iberian peninsula. During the 1st century BCE Nîmes gradually broke away from the influence of Marseilles to gradually enter into the orbit of Rome. After the conquest of Marseilles by Caesar, the Romanisation of Nîmes accelerated further with the city then receiving the title of Colonia Augusta Nemausus, allowing the city to keep a certain autonomy without the Romanisation being slowed down. Architecturally, the city took on an increasingly Roman form with an important appearance of several buildings of a public nature. Similarly, dwellings are shifting more and more from the hills to the plain which became a true symbol of the urban expansion of Nîmes.

The development of the city of Nîmes further intensified due to its geographical location, since the city was crossed by the via Domitia and the Heraclean way. The via Domitia would become essential in the economic development of the city since its led from Italy to the Iberian peninsula. During the 1st century BCE Nîmes gradually broke away from the influence of Marseilles to gradually enter into the orbit of Rome. After the conquest of Marseilles by Caesar, the Romanisation of Nîmes accelerated further with the city then receiving the title of Colonia Augusta Nemausus, allowing the city to keep a certain autonomy without the Romanisation being slowed down. Architecturally, the city took on an increasingly Roman form with an important appearance of several buildings of a public nature. Similarly, dwellings are shifting more and more from the hills to the plain which became a true symbol of the urban expansion of Nîmes.

A

crocodile chained to a palm tree with the inscription COL NEM, for

Colonia Nemausus, (the colony of Nemausus, the

local Celtic god of the Volcae Arecomici) can be seen all over the city,

from elegant representations on the balcony of the town hall to more

prosaic examples on the cast iron manhole covers scattered along the old

winding streets of the town centre. According to one plausible theory

the origins of this emblem may go back more than 2,000 years to

September 31 BCE when the fleet of Octavian, nephew of Julius Caesar and

future emperor, defeated that of Mark Antony and Cleopatra in the naval

battle at Actium. By the

time of the Battle of Actium, Mark Antony was based in Egypt. He was

personally and politically united with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra who

was present at the Battle, and they both fled back to Egypt after their

defeat. Consequently the victory at Actium would have been viewed as

the defeat of Egypt, not just the defeat of Mark Antony himself, a point

Augustus stressed regularly not least in the erection and dedication of

Egyptian obelisks in Rome. This victory, and Antony's subsequent

suicide in Egypt in 30 BCE, left

Octavian in undisputed control of Rome and all its territories. The

crocodile was frequently used to represent Egypt and a chained crocodile

surmounted by a laurel crown (as worn by the Roman Emperor) quite

clearly symbolised the submission of Egypt to Roman control. But his

official reign as Rome's first emperor is usually considered not to have

begun until January 27 BCE when among many other honours offered to him

by the Senate he accepted the title of 'Augustus', which he adopted as

his personal name and by which he was known for the rest of his long

life. Veterans of the Roman legions

who had served Julius Caesar in his Nile campaigns, at the end of

fifteen years of soldiering, were given plots of land to cultivate on

the plain of Nîmes.

The Maison Carrée during the Nazi occupation and today. During its construction, the Maison Carrée was dedicated for Augustus to the glory of his two grandsons, the consuls and military leaders Lucius Caesar and Gaius Julius Caesar. Over the centuries, the temple notably became a consular house, a church and then a museum of ancient arts. Today it is the best preserved Roman temple in the world. The Maison Carrée is a Corinthian and pseudo- peripteral hexastyle building , which measures 13.54 metres in width by 26.42 metres in length. Its thirty columns, each nine metres high, enclose the interior structure which is comprised of a cella, preceded by a pronaos whose ceiling is modern. Originally, one had to enter the cella through a large door almost seven metres high. The temple was built on a high podium which gave it a dominant position on its environment. Access to the cella is via a single staircase of fifteen steps; the number of steps always odd which was reserved for priests.

The Maison Carrée during the Nazi occupation and today. During its construction, the Maison Carrée was dedicated for Augustus to the glory of his two grandsons, the consuls and military leaders Lucius Caesar and Gaius Julius Caesar. Over the centuries, the temple notably became a consular house, a church and then a museum of ancient arts. Today it is the best preserved Roman temple in the world. The Maison Carrée is a Corinthian and pseudo- peripteral hexastyle building , which measures 13.54 metres in width by 26.42 metres in length. Its thirty columns, each nine metres high, enclose the interior structure which is comprised of a cella, preceded by a pronaos whose ceiling is modern. Originally, one had to enter the cella through a large door almost seven metres high. The temple was built on a high podium which gave it a dominant position on its environment. Access to the cella is via a single staircase of fifteen steps; the number of steps always odd which was reserved for priests.  The function of the cella was to house the statue of the honoured god or gods. The ceremonies took place around an altar placed in front of the entrance. Its architecture was directly inspired by the Temple of Apollo in Rome, of which the Maison Carrée is a reduced model. As far as the decoration is concerned, it is essentially formed by the entablature and the capitals of the columns that support it. Its composition includes an architrave divided into three bands and adorned with a scrollwork frieze. On the right the wife and son inside, where no trace of the original decor has been preserved, although it has been reconstructed. They're beside the large 6.87 metres high by 3.27 metres wide door leading to the surprisingly

small and windowless interior, where the shrine was originally housed which when we visited was used to house a tourist-oriented film on a the Roman history

of Nîmes. Building a religious building presupposes an authorisation from the authorities, in this case from Augustus. Its execution, even if it is entrusted to regional teams, would have been strictly supervised as only models inspired by the official creations of Rome could be built. The Corinthian order decoration of the colonnade are faithful to the model of the temple of Mars Ultor in Rome. The frieze is composed of winding scrolls of acanthus, imitating the frieze of the Ara Pacis in Rome.

The function of the cella was to house the statue of the honoured god or gods. The ceremonies took place around an altar placed in front of the entrance. Its architecture was directly inspired by the Temple of Apollo in Rome, of which the Maison Carrée is a reduced model. As far as the decoration is concerned, it is essentially formed by the entablature and the capitals of the columns that support it. Its composition includes an architrave divided into three bands and adorned with a scrollwork frieze. On the right the wife and son inside, where no trace of the original decor has been preserved, although it has been reconstructed. They're beside the large 6.87 metres high by 3.27 metres wide door leading to the surprisingly

small and windowless interior, where the shrine was originally housed which when we visited was used to house a tourist-oriented film on a the Roman history

of Nîmes. Building a religious building presupposes an authorisation from the authorities, in this case from Augustus. Its execution, even if it is entrusted to regional teams, would have been strictly supervised as only models inspired by the official creations of Rome could be built. The Corinthian order decoration of the colonnade are faithful to the model of the temple of Mars Ultor in Rome. The frieze is composed of winding scrolls of acanthus, imitating the frieze of the Ara Pacis in Rome. .gif) The temple carried on its frontispiece , inscribed in bronze letters sealed in the stone a dedication which has since disappeared but, thanks to the arrangement of the still visible sealing holes, the great Nîmes scholar Jean-François Séguier managed in 1758 to recompose the original text: "To Caius Caesar consul and Lucius Caesar consul designated, son of Augustus, princes of youth." Gaius and Lucius were the sons of Agrippa and Julia, the disgraced daughter of Augustus. Agrippa was Augustus' closest adviser and assistant who was the patron of the city of Nemausus, serving as the official defender of the interests of the city and of the community of citizens before the Senate of Rome. When he died he passed on the patronage to his eldest son Gaius. On the death of Gaius and Lucius, the people of Nîmes, with the agreement of the authorities in Rome, decided to dedicate this temple to them. Thanks to the first line of this dedication, it is possible to date the completion of the Square House between the years 2 and 3, according to the date of the consulship of Gaius and Lucius. The second line, placed later, dates from years 4-5.

The temple carried on its frontispiece , inscribed in bronze letters sealed in the stone a dedication which has since disappeared but, thanks to the arrangement of the still visible sealing holes, the great Nîmes scholar Jean-François Séguier managed in 1758 to recompose the original text: "To Caius Caesar consul and Lucius Caesar consul designated, son of Augustus, princes of youth." Gaius and Lucius were the sons of Agrippa and Julia, the disgraced daughter of Augustus. Agrippa was Augustus' closest adviser and assistant who was the patron of the city of Nemausus, serving as the official defender of the interests of the city and of the community of citizens before the Senate of Rome. When he died he passed on the patronage to his eldest son Gaius. On the death of Gaius and Lucius, the people of Nîmes, with the agreement of the authorities in Rome, decided to dedicate this temple to them. Thanks to the first line of this dedication, it is possible to date the completion of the Square House between the years 2 and 3, according to the date of the consulship of Gaius and Lucius. The second line, placed later, dates from years 4-5. .gif) The GIFs here of us show the temple before and after its impressive restoration which took no less than four years and more than 44,000 hours of work for the teams of the architect of historical monuments, Thierry Algrin, to complete. From 2006-2007, the south facade of the Maison Carrée benefited from a renovation which allowed it to regain a sometimes disputed whiteness. This long work continued in 2007-2008 with the west facade, in 2008-2009 with the east facade and finally, in 2009-2010 for the main facade, on which it was planned to restore the bronze letters of the original dedication. Due to its multiple uses over the past 2000 years, the decor of the interior of the Maison Carrée has not been preserved; only its exterior appearance is intact. Certainly the post-Roman history of the building is eventful; in fact, it's almost miraculous that it has come to this day in such good condition. From the 11th to the 16th centuries, the Maison Carrée was used as the consular house of Nîmes; a sort of town hall during the time in the Middle Ages when certain aldermen of the South of France were called consuls. The building was then known as the Capitole or Cap-duel when it then underwent numerous transformations to adapt it to the needs of its new occupants.

The GIFs here of us show the temple before and after its impressive restoration which took no less than four years and more than 44,000 hours of work for the teams of the architect of historical monuments, Thierry Algrin, to complete. From 2006-2007, the south facade of the Maison Carrée benefited from a renovation which allowed it to regain a sometimes disputed whiteness. This long work continued in 2007-2008 with the west facade, in 2008-2009 with the east facade and finally, in 2009-2010 for the main facade, on which it was planned to restore the bronze letters of the original dedication. Due to its multiple uses over the past 2000 years, the decor of the interior of the Maison Carrée has not been preserved; only its exterior appearance is intact. Certainly the post-Roman history of the building is eventful; in fact, it's almost miraculous that it has come to this day in such good condition. From the 11th to the 16th centuries, the Maison Carrée was used as the consular house of Nîmes; a sort of town hall during the time in the Middle Ages when certain aldermen of the South of France were called consuls. The building was then known as the Capitole or Cap-duel when it then underwent numerous transformations to adapt it to the needs of its new occupants. .gif) The Nîmes historian Léon Ménard gives a description of these transformations imposed on the ancient Roman temple: “First the interior was divided into several rooms, and even into two floors; vaults were formed there, a chimney was built there, which was leaned against the east wall, and a spiral staircase against that of the west. In addition, to light these new apartments, several square windows were made there . The consuls subsequently added something to this order. They had the vestibule closed by a wall, which went from one column to the other, so other windows were opened and a cellar was made in the underground vault of the vestibule. The porch was also knocked down." It became a dwelling house, a stable and then a church of the Augustins. It was intended by the Duchess of Uzès to serve as a tomb for her husband, Antoine de Crussol. During the French Revolution it served as the meeting place of the Directory and then became the prefecture of the Gard department between 1800 and 1807. Restored, like the other monuments of Nîmes in the 19th century, the Maison Carrée bears engraved in Roman letters on the western flank a short text in Latin: "Repaired by the munificence of the king and the money offered by the citizens, 1822." 170 years later in 1992 the Maison Carrée received a new roof, a faithful reproduction of the antique original, made up of large flat tiles ( tegulae ) and hand-moulded canal tiles (imbrices).

The Nîmes historian Léon Ménard gives a description of these transformations imposed on the ancient Roman temple: “First the interior was divided into several rooms, and even into two floors; vaults were formed there, a chimney was built there, which was leaned against the east wall, and a spiral staircase against that of the west. In addition, to light these new apartments, several square windows were made there . The consuls subsequently added something to this order. They had the vestibule closed by a wall, which went from one column to the other, so other windows were opened and a cellar was made in the underground vault of the vestibule. The porch was also knocked down." It became a dwelling house, a stable and then a church of the Augustins. It was intended by the Duchess of Uzès to serve as a tomb for her husband, Antoine de Crussol. During the French Revolution it served as the meeting place of the Directory and then became the prefecture of the Gard department between 1800 and 1807. Restored, like the other monuments of Nîmes in the 19th century, the Maison Carrée bears engraved in Roman letters on the western flank a short text in Latin: "Repaired by the munificence of the king and the money offered by the citizens, 1822." 170 years later in 1992 the Maison Carrée received a new roof, a faithful reproduction of the antique original, made up of large flat tiles ( tegulae ) and hand-moulded canal tiles (imbrices).

Germans marching past the former theatre which was destroyed by fire in 1952. Only its remarkable ionic colonnade was preserved and relocated to the Caissargues rest area on the A54 between Nîmes and Arles.

Interior of the Temple of Diana in Nîmes, a large oil painting intended to decorate a living room in the Château de Fontainebleau from the series Principal Monuments of France by painter Hubert Robert and how it appears today. The Temple of Diana is a Roman ruin located in Nîmes accessible by the Jardins de la Fontaine. Today the building is believed to have been the library of a complex of facilities dedicated to Augustus which included a small theatre. It's dated from the 1st century CE, but it might have been partly redesigned in the following century. Hubert Robert made several versions of it, including an initial one from 1771 probably taken from a sketch made from memory in Rome and which includes several imaginary details (bas-relief of the tympanum, coffers of the vault, inversion of the pediments of the niches, columns, statues, et cet.), some reinforcing the fantasy ruin aspect (missing lintels on the left as on all versions while they are still in place today or even in 1826 as Charles Léopold Émile Henry's view suggests). The paintings have been kept in the Louvre Museum since 1822 following the legacy of the painter's widow.

Its atmospheric ruins probably date from the Antonine period in the 2nd Century. It's not clear what the real purpose of this building was, but it was probably not a temple. It's been suggested that it might have been an Imperial cult centre or even a library.Juxtaposed against the Roman grandeur of the adjacent Maison Carrée and the modernist Carré d'Art, the Temple of Diana embodies a continuity of historical identities, from Roman Gaul to Vichy France and beyond. The site's wartime history is especially complex. During the period of Vichy governance and Nazi occupation, the Temple of Diana took on conflicting roles.

Its atmospheric ruins probably date from the Antonine period in the 2nd Century. It's not clear what the real purpose of this building was, but it was probably not a temple. It's been suggested that it might have been an Imperial cult centre or even a library.Juxtaposed against the Roman grandeur of the adjacent Maison Carrée and the modernist Carré d'Art, the Temple of Diana embodies a continuity of historical identities, from Roman Gaul to Vichy France and beyond. The site's wartime history is especially complex. During the period of Vichy governance and Nazi occupation, the Temple of Diana took on conflicting roles.  During the era of Vichy France and Nazi occupation, the Temple of Diana, along with other significant historical sites, was co-opted for various propaganda efforts aimed at fostering a unified national identity. Such architectural monuments were used to support the ideological framework that the Vichy regime was constructing. This regime yearned for a return to a mythic, cohesive national past that they believed the temple symbolised. However, in doing so, they inadvertently created a space that invited subversion. On the one hand, it served as a place of solace and inspiration for members of the Resistance, who viewed it as a symbol of enduring French culture and civilisation.

During the era of Vichy France and Nazi occupation, the Temple of Diana, along with other significant historical sites, was co-opted for various propaganda efforts aimed at fostering a unified national identity. Such architectural monuments were used to support the ideological framework that the Vichy regime was constructing. This regime yearned for a return to a mythic, cohesive national past that they believed the temple symbolised. However, in doing so, they inadvertently created a space that invited subversion. On the one hand, it served as a place of solace and inspiration for members of the Resistance, who viewed it as a symbol of enduring French culture and civilisation.  On the other hand, the Vichy regime, eager to tie its ideology to a grand French past, often used it for propagandistic purposes. The site thus became a contested space, symbolising the struggle for the soul of France itself. Jackson argues that the Vichy regime's selective veneration of French history, including sites like the Temple of Diana, was a deliberate attempt to cultivate nationalist sentiment, which ironically also fostered spaces that would harbour the Resistance. The regime’s ideological paradox is encapsulated by the temple; while attempting to control and define the narrative of French identity, it inadvertently provided a haven for forces that would eventually lead to its downfall. The Temple of Diana's wartime history further complicates France's collective memory, emphasizing the necessity to approach such sites with nuanced understanding, beyond simplistic narratives of collaboration or resistance. It serves as a poignant reminder that historical sites are not just passive settings where events unfold; they are dynamic spaces that participate in shaping the socio-political fabric of their times.

On the other hand, the Vichy regime, eager to tie its ideology to a grand French past, often used it for propagandistic purposes. The site thus became a contested space, symbolising the struggle for the soul of France itself. Jackson argues that the Vichy regime's selective veneration of French history, including sites like the Temple of Diana, was a deliberate attempt to cultivate nationalist sentiment, which ironically also fostered spaces that would harbour the Resistance. The regime’s ideological paradox is encapsulated by the temple; while attempting to control and define the narrative of French identity, it inadvertently provided a haven for forces that would eventually lead to its downfall. The Temple of Diana's wartime history further complicates France's collective memory, emphasizing the necessity to approach such sites with nuanced understanding, beyond simplistic narratives of collaboration or resistance. It serves as a poignant reminder that historical sites are not just passive settings where events unfold; they are dynamic spaces that participate in shaping the socio-political fabric of their times. The Arena of Nîmes is a Roman amphitheatre built around 70 CE. As the Roman Empire fell, the amphitheatre was fortified by the Visigoths and was surrounded by a wall. During the turbulent years that followed the collapse of Visigoth power in Hispania and Septimania, not to mention the Muslim invasion and subsequent conquest by the French kings in the mid eighth century, the viscounts of Nîmes constructed a fortified palace within the amphitheatre. In 737, after failing to seize Narbonne, Charles Martel destroyed a number of Septimanian cities on his way north, including Nîmes and its amphitheatre, as asserted in the Continuations of Fredegar. Later a small neighbourhood developed within its confines, complete with one hundred denizens and two chapels. Seven hundred people lived within the amphitheatre during the apex of its service as an enclosed community. The buildings remained in the amphitheatre until the eighteenth century, when the decision was made to convert the amphitheatre into its present form.

The Arena of Nîmes is a Roman amphitheatre built around 70 CE. As the Roman Empire fell, the amphitheatre was fortified by the Visigoths and was surrounded by a wall. During the turbulent years that followed the collapse of Visigoth power in Hispania and Septimania, not to mention the Muslim invasion and subsequent conquest by the French kings in the mid eighth century, the viscounts of Nîmes constructed a fortified palace within the amphitheatre. In 737, after failing to seize Narbonne, Charles Martel destroyed a number of Septimanian cities on his way north, including Nîmes and its amphitheatre, as asserted in the Continuations of Fredegar. Later a small neighbourhood developed within its confines, complete with one hundred denizens and two chapels. Seven hundred people lived within the amphitheatre during the apex of its service as an enclosed community. The buildings remained in the amphitheatre until the eighteenth century, when the decision was made to convert the amphitheatre into its present form. .gif) Local Frenchmen enthusiastically saluting the occupying Germans in front of la fontaine Pradier. In November 1940 the Nîmes Committee (Coordinating Committee for Camp Aid) was created, headed by American Dr. Donald Lowrie, representing the International YMCA. It aimed to support and save refugees throughout France, writing and distributing numerous reports regarding conditions in the camps. Members of the organisations united under the Committee established contacts, developed procedures, created networks of cooperation, and established orphanages and safe houses that served as a pre-existing infrastructure available for rescue efforts when the deportation crisis struck in August 1942, allowing them to deal directly both with Vichy officials and the French public at large. Of its remarkable work, Bob Moore emphasised the level of cooperation it was able to forge between different Christian groups as well as that between Jewish and non-Jewish agencies as a “crucial factor” in the rescue and survival of French Jews, with Lucien Lazare concurring, explaining how such "organisations active in the camps had become familiar with the administrative and police machinery and knew its weak points. Trust and by now longstanding cooperation between the activists of various humanitarian associations grouped with the Nîmes Committee facilitated the rapid formation of rescue networks.”

Local Frenchmen enthusiastically saluting the occupying Germans in front of la fontaine Pradier. In November 1940 the Nîmes Committee (Coordinating Committee for Camp Aid) was created, headed by American Dr. Donald Lowrie, representing the International YMCA. It aimed to support and save refugees throughout France, writing and distributing numerous reports regarding conditions in the camps. Members of the organisations united under the Committee established contacts, developed procedures, created networks of cooperation, and established orphanages and safe houses that served as a pre-existing infrastructure available for rescue efforts when the deportation crisis struck in August 1942, allowing them to deal directly both with Vichy officials and the French public at large. Of its remarkable work, Bob Moore emphasised the level of cooperation it was able to forge between different Christian groups as well as that between Jewish and non-Jewish agencies as a “crucial factor” in the rescue and survival of French Jews, with Lucien Lazare concurring, explaining how such "organisations active in the camps had become familiar with the administrative and police machinery and knew its weak points. Trust and by now longstanding cooperation between the activists of various humanitarian associations grouped with the Nîmes Committee facilitated the rapid formation of rescue networks.”  On the other hand, just under an hundred individuals were known to belong to collaborationist organisations in and around Nîmes with approximately 270 members of the local Groupe Collaboration promoting closer ties with the Nazis. Postwar, De Gaulle’s Intelligence Service reported that, around Nîmes, the JEN- Jeunes de l’Europe Nouvelle- helped the Gestapo locate those who had dodged the labour draft.

On the other hand, just under an hundred individuals were known to belong to collaborationist organisations in and around Nîmes with approximately 270 members of the local Groupe Collaboration promoting closer ties with the Nazis. Postwar, De Gaulle’s Intelligence Service reported that, around Nîmes, the JEN- Jeunes de l’Europe Nouvelle- helped the Gestapo locate those who had dodged the labour draft. Nevertheless, France's active involvement in the Holocaust was seen here with the Nîmes and Avignon roundups of Jews on April 19, 1943 which would culminate in the mass murder of 22,000 French Jews. Already by 1942 42,000 Jews were deported from France and systematically murdered.  It has since transpired that a list of every Jew resident in Nîmes during the occupation was discovered in the private papers of local historian Lucien Simon. Under the address section of twelve of the names, it was marked "Chantiers de la Jeunesse". Only one of the twelve men, Philippe Presberg, was ever located, and he agreed to be interviewed in February 2009. It is known that two of the men, Prosper Chich and André Lévy, were deported to Auschwitz after the SS began large scale arrests of Jews not only in Nîmes but Avignon, Carpentras and Aix. The arrested Jews were then taken from Marseilles to Drancy. In the final year of France's collaboration, 12,500 Jews were deported from France and murdered, making the total number of Jews deported and murdered in France to be 75,000 out of a population of 375,000 Jews in the country- a full quarter of the population. Not surprisingly, there is little information about Nîmes during this time, a conspiracy of silence that began to be confronted from the 1990s onwards when increasing demands for plaques related to the Holocaust became louder. One result of this can be seen at the main railway station dedicated to the memory of deported children located in the entrance hall on the western wall.

It has since transpired that a list of every Jew resident in Nîmes during the occupation was discovered in the private papers of local historian Lucien Simon. Under the address section of twelve of the names, it was marked "Chantiers de la Jeunesse". Only one of the twelve men, Philippe Presberg, was ever located, and he agreed to be interviewed in February 2009. It is known that two of the men, Prosper Chich and André Lévy, were deported to Auschwitz after the SS began large scale arrests of Jews not only in Nîmes but Avignon, Carpentras and Aix. The arrested Jews were then taken from Marseilles to Drancy. In the final year of France's collaboration, 12,500 Jews were deported from France and murdered, making the total number of Jews deported and murdered in France to be 75,000 out of a population of 375,000 Jews in the country- a full quarter of the population. Not surprisingly, there is little information about Nîmes during this time, a conspiracy of silence that began to be confronted from the 1990s onwards when increasing demands for plaques related to the Holocaust became louder. One result of this can be seen at the main railway station dedicated to the memory of deported children located in the entrance hall on the western wall.

It has since transpired that a list of every Jew resident in Nîmes during the occupation was discovered in the private papers of local historian Lucien Simon. Under the address section of twelve of the names, it was marked "Chantiers de la Jeunesse". Only one of the twelve men, Philippe Presberg, was ever located, and he agreed to be interviewed in February 2009. It is known that two of the men, Prosper Chich and André Lévy, were deported to Auschwitz after the SS began large scale arrests of Jews not only in Nîmes but Avignon, Carpentras and Aix. The arrested Jews were then taken from Marseilles to Drancy. In the final year of France's collaboration, 12,500 Jews were deported from France and murdered, making the total number of Jews deported and murdered in France to be 75,000 out of a population of 375,000 Jews in the country- a full quarter of the population. Not surprisingly, there is little information about Nîmes during this time, a conspiracy of silence that began to be confronted from the 1990s onwards when increasing demands for plaques related to the Holocaust became louder. One result of this can be seen at the main railway station dedicated to the memory of deported children located in the entrance hall on the western wall.

It has since transpired that a list of every Jew resident in Nîmes during the occupation was discovered in the private papers of local historian Lucien Simon. Under the address section of twelve of the names, it was marked "Chantiers de la Jeunesse". Only one of the twelve men, Philippe Presberg, was ever located, and he agreed to be interviewed in February 2009. It is known that two of the men, Prosper Chich and André Lévy, were deported to Auschwitz after the SS began large scale arrests of Jews not only in Nîmes but Avignon, Carpentras and Aix. The arrested Jews were then taken from Marseilles to Drancy. In the final year of France's collaboration, 12,500 Jews were deported from France and murdered, making the total number of Jews deported and murdered in France to be 75,000 out of a population of 375,000 Jews in the country- a full quarter of the population. Not surprisingly, there is little information about Nîmes during this time, a conspiracy of silence that began to be confronted from the 1990s onwards when increasing demands for plaques related to the Holocaust became louder. One result of this can be seen at the main railway station dedicated to the memory of deported children located in the entrance hall on the western wall. The statue of Pan in front of German soldiers in the Nymphaeum.

Birthplace

of Bernard Lazare, French Jewish literary critic, political journalist,

polemicist, and anarchist who was among the first Dreyfusards. Given

his reputation for combativeness and courage, Lazare was contacted by

Mathieu Dreyfus to help prove his brother's innocence. Lazare devoted

his time exclusively to the case, publishing his first paper, The Dreyfus Affair – A Miscarriage of Justice

in Belgium in November 1896. In it, Lazare refuted the accusation point

by point and demanded the sentence be overturned. The first version of

the text was a savage attack on the accusers, ending with the phrase

"J’accuse", later made famous by Émile Zola.

Birthplace

of Bernard Lazare, French Jewish literary critic, political journalist,

polemicist, and anarchist who was among the first Dreyfusards. Given

his reputation for combativeness and courage, Lazare was contacted by

Mathieu Dreyfus to help prove his brother's innocence. Lazare devoted

his time exclusively to the case, publishing his first paper, The Dreyfus Affair – A Miscarriage of Justice

in Belgium in November 1896. In it, Lazare refuted the accusation point

by point and demanded the sentence be overturned. The first version of

the text was a savage attack on the accusers, ending with the phrase

"J’accuse", later made famous by Émile Zola. Pont du Gard, an ancient Roman aqueduct crossing the Gardon River near the town of Vers-Pont-du-Gard. It's part of the Nîmes aqueduct, a 50-kilometre system built in the first century AD to carry water from a spring at Uzès to the Nemausus. It used to be dated to Augustus, but new excavations suggest the aqueduct was built 40–80, probably under Claudius. Because of the uneven terrain between the two points, the mostly underground aqueduct followed a long, winding route that required a bridge across the gorge of the Gardon River. The Pont du Gard is the highest of all elevated Roman aqueducts, and is unique in having three tiers of arches, standing 160 feet high. The whole aqueduct descends in height by only 56 feet over its entire length, whilst the bridge descends by a mere inch – a gradient of only 1 in 3,000 – which demonstrates the great precision that Roman engineers were able to achieve using only simple technology. The aqueduct formerly carried an estimated 44,000,000 imperial gallons of water a day to the fountains, baths and homes of the citizens of Nîmes. It continued to be used possibly until the 6th century, some parts for significantly longer, but lack of maintenance after the 4th century meant that it became increasingly clogged by mineral deposits and debris that eventually choked off the flow of water. After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the aqueduct's fall into disuse, the Pont du Gard remained largely intact due to the importance of its secondary function, as a toll bridge. For centuries the local lords and bishops were responsible for its upkeep, in exchange for the right to levy tolls on travellers using it to cross the river, although some of its stones were looted and serious damage was inflicted on it in the 17th century.

Pont du Gard, an ancient Roman aqueduct crossing the Gardon River near the town of Vers-Pont-du-Gard. It's part of the Nîmes aqueduct, a 50-kilometre system built in the first century AD to carry water from a spring at Uzès to the Nemausus. It used to be dated to Augustus, but new excavations suggest the aqueduct was built 40–80, probably under Claudius. Because of the uneven terrain between the two points, the mostly underground aqueduct followed a long, winding route that required a bridge across the gorge of the Gardon River. The Pont du Gard is the highest of all elevated Roman aqueducts, and is unique in having three tiers of arches, standing 160 feet high. The whole aqueduct descends in height by only 56 feet over its entire length, whilst the bridge descends by a mere inch – a gradient of only 1 in 3,000 – which demonstrates the great precision that Roman engineers were able to achieve using only simple technology. The aqueduct formerly carried an estimated 44,000,000 imperial gallons of water a day to the fountains, baths and homes of the citizens of Nîmes. It continued to be used possibly until the 6th century, some parts for significantly longer, but lack of maintenance after the 4th century meant that it became increasingly clogged by mineral deposits and debris that eventually choked off the flow of water. After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the aqueduct's fall into disuse, the Pont du Gard remained largely intact due to the importance of its secondary function, as a toll bridge. For centuries the local lords and bishops were responsible for its upkeep, in exchange for the right to levy tolls on travellers using it to cross the river, although some of its stones were looted and serious damage was inflicted on it in the 17th century.

Glanum

At the Mausoleum of the Julii, located across the Via Domitia, to the north of, and just outside the city entrance, dating to about 40 BCE, and is one of the best preserved mausoleums of the Roman era. It's considered a cenotaph erected in memory of a man of the Julii family

who was granted citizenship and his name by Julius Caesar for his

service in the Roman army, following the conquest of Gaul. Henri

Rolland suggests that it was a mausoleum dedicated to the memory of Gaius and Lucius Caesar, grandsons of Augustus. With the Arch of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence a few metres away, it forms