Home of infamous Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, publisher of Der Stürmer and Gauleiter of Franconia, Nuremberg held especial significance for the Nazis. It was because of the city's relevance to the Holy Roman Empire and its position in the centre of Germany that the Nazis chose the city to be the site of huge Nazi Party conventions–the Nuremberg rallies- held annually from 1927 to 1938. After Hitler's rise to power in 1933 the rallies became huge state propaganda events, a centre of anti-Semitism and other Nazi ideals. It was at the 1935 rally that Hitler specifically ordered the Reichstag to convene at Nuremberg to pass the Nuremberg Laws which revoked German citizenship specifically for Jews, Afro-Germans, and gypsies from German citizenship; to this day one could be born in Germany yet not be allowed citizenship as in the case of my son. A number of premises were constructed solely for these assemblies, some of which were not finished and so many examples of Nazi architecture can still be seen in the city today.

Home of infamous Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, publisher of Der Stürmer and Gauleiter of Franconia, Nuremberg held especial significance for the Nazis. It was because of the city's relevance to the Holy Roman Empire and its position in the centre of Germany that the Nazis chose the city to be the site of huge Nazi Party conventions–the Nuremberg rallies- held annually from 1927 to 1938. After Hitler's rise to power in 1933 the rallies became huge state propaganda events, a centre of anti-Semitism and other Nazi ideals. It was at the 1935 rally that Hitler specifically ordered the Reichstag to convene at Nuremberg to pass the Nuremberg Laws which revoked German citizenship specifically for Jews, Afro-Germans, and gypsies from German citizenship; to this day one could be born in Germany yet not be allowed citizenship as in the case of my son. A number of premises were constructed solely for these assemblies, some of which were not finished and so many examples of Nazi architecture can still be seen in the city today.The site of the rallies on the outskirts of Nuremberg, particularly the enormous Zeppelin Meadow, was conspicuous for its monumental architecture and landscaping. The Nazis pioneered elaborate staging and lighting techniques to give the annual celebrations the character of sacred religious rituals with Hitler in the role of High Priest. The function of the ceremonies was to manufacture ecstasy and consensus, eliminate all reflective and critical consciousness, and instil in Germans a desire to submerge their individuality in a higher national cause.

In 1933 and 1934, the Zeppelinfeld meadow served as a parade ground for the Nazis during their Party Rallies. They put up temporary wooden stands for the spectators but by 1935–1936, the Zeppelin Field, complete with stone stands, was constructed to plans by architect Albert Speer. The complex is almost square, and centres on the monumental Grandstand with the “Führer’s Rostrum”. The visibly lower spectators’ stands on the other three sides were divided by these flag supporters. There were 34 of them mounting six flag poles which surrounded the Zeppelinfeld, dividing the seating areas and providing toilet facilities. The interior which measured 312 by 285 metres provided space for up to 200,000 people for the mass events staged by the Nazis.

In 1933 and 1934, the Zeppelinfeld meadow served as a parade ground for the Nazis during their Party Rallies. They put up temporary wooden stands for the spectators but by 1935–1936, the Zeppelin Field, complete with stone stands, was constructed to plans by architect Albert Speer. The complex is almost square, and centres on the monumental Grandstand with the “Führer’s Rostrum”. The visibly lower spectators’ stands on the other three sides were divided by these flag supporters. There were 34 of them mounting six flag poles which surrounded the Zeppelinfeld, dividing the seating areas and providing toilet facilities. The interior which measured 312 by 285 metres provided space for up to 200,000 people for the mass events staged by the Nazis. |

| The so-called 'Cathedral of Ice.' |

We are proud of you! All of Germany loves you! For you are not merely bearers of the spade, but rather you have become bearers of the shield for our Reich and Volk! You represent the most noble of slogans known to us: “God helps those who help themselves!” I thank you for your creations and work! I thank your Reich Leader of Labour Service for the gigantic build-up accomplished! As Führer and Chancellor of the Reich, I rejoice at this sight, standing before you, and I rejoice in recognition of the spirit that inspires you, and I rejoice at seeing my Volk which possesses such men and maids! Heil Euch!

According to Speer (66) in Inside the Third Reich:

|

| My Bavarian International School students in 2012 |

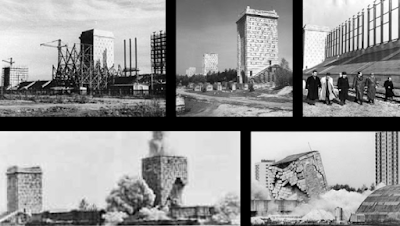

To clear the ground for it, the Nuremberg streetcar depot had to be removed. I passed by its remains after it had been blown up. The iron reinforcements protruded from concrete debris and had already begun to rust. One could easily visualise their further decay. This dreary sight led me to some thoughts which I later propounded to Hitler under the pretentious heading of ' The idea was that buildings of modern construction were poorly suited to form that to future generations which Hitler was calling for. It was hard to imagine that rusting heaps of rubble could communicate these heroic inspirations which Hitler admired in the monuments of the past. By using special materials and by applying certain principles of statics, we should be able to build structures which even in a state of decay, after hundreds or (such were our reckonings) thousands of years would more or less resemble Roman models.

To illustrate my ideas I had a romantic drawing prepared. It showed what the reviewing stand on the Zeppelin Field would look like after generations of neglect, overgrown with ivy, its columns fallen, the walls crumbling here and there, but the outlines still clearly recognisable. In Hitler's entourage this drawing was regarded as blasphemous. That I could even conceive of a period of decline for the newly founded Reich destined to last a thousand years seemed outrageous to many of Hitler's closest followers. But he himself accepted my ideas as logical and illuminating. He gave orders that in the future the important buildings of his Reich were to be erected in keeping with the principles of this.

To illustrate my ideas I had a romantic drawing prepared. It showed what the reviewing stand on the Zeppelin Field would look like after generations of neglect, overgrown with ivy, its columns fallen, the walls crumbling here and there, but the outlines still clearly recognisable. In Hitler's entourage this drawing was regarded as blasphemous. That I could even conceive of a period of decline for the newly founded Reich destined to last a thousand years seemed outrageous to many of Hitler's closest followers. But he himself accepted my ideas as logical and illuminating. He gave orders that in the future the important buildings of his Reich were to be erected in keeping with the principles of this.

Standing

on the Zeppelintribüne's rostrum today positioned in the centre of the grandstand for which all participants of the party rally on the field, including political leaders, had to look up to Hitler just as much as the other spectators. Seen from afar, the rostrum was further emphasised by the golden swastika placed above and by a Nazi flag draped on it. It was positioned on the main axis of the Zeppelin Field so that the men of the Reich Labour Service would always march towards the swastikas and the rostrum, thus getting ever closer to Hitler. The grandstand served to confront the Führer with his followers in such a way that every year his leadership was symbolically reconfirmed and thus strengthened by forcing participants to line up before him and pledge allegiance to him. The spectators were witnesses to this staged oath of allegiance and thus became part of the “national community” which took a subordinate role to the Führer.

Standing

on the Zeppelintribüne's rostrum today positioned in the centre of the grandstand for which all participants of the party rally on the field, including political leaders, had to look up to Hitler just as much as the other spectators. Seen from afar, the rostrum was further emphasised by the golden swastika placed above and by a Nazi flag draped on it. It was positioned on the main axis of the Zeppelin Field so that the men of the Reich Labour Service would always march towards the swastikas and the rostrum, thus getting ever closer to Hitler. The grandstand served to confront the Führer with his followers in such a way that every year his leadership was symbolically reconfirmed and thus strengthened by forcing participants to line up before him and pledge allegiance to him. The spectators were witnesses to this staged oath of allegiance and thus became part of the “national community” which took a subordinate role to the Führer.In June 2006, five matches of the World Cup were held at the municipal stadium in the Volkspark Dutzendteic which is now a public park that once was the Nazi Party rally grounds. Tournament organisers feared that the remains of the Nazi era buildings surrounding the stadium would be glorified, expressing concerns about misuse by the infamous English soccer hooligans in particular. In December 2005, the Times Online published how "[i]t does not take a big leap of imagination to see England fans mimicking the goose-step march heading for the Zeppelin Tribune from where Hitler took the salute from the massed ranks of party faithful." Nuremberg Mayor Ulr Maly rejected the idea of a "no go" zone for English fans, but added that the police would be mobilised immediately if anybody was seen making Hitler salutes, forbidden by German law even though I've never noticed any such authoritarian presence.

How far the materiality of the site is suggestive directly to the senses or emotions, rather than being actively interpreted by visitors, is more difficult to determine. Certainly, physical qualities make practical differences to how people use it. The walls of the Zeppelin Building making for such good tennis practice, or the outer corridors of the Congress Hall providing quiet shelter in which to sleep rough, are just a couple of examples of uses of the site that were never originally intended but to which its material qualities lend themselves. But what of the intended Nazi effects? How far are the buildings and former marching grounds still able to impact and enchant in the ways that Hitler and Speer had hoped? Watching people using the place and hearing them talk about it, it seemed to me that there was little to indicate much of this. Certainly, some would stand where Hitler would have stood on the Zeppelin Building, and they might even give a Nazi salute, but this was typically accompanied by joking and parody. And, certainly, some visitors talked of the chilling nature of the site, prompting them to quiet reflection... in all of their accounts it seemed that what was involved was not so much being directly affected by particular calculated features of the architecture as by their own pre-formed visions of it. They accounted for their senses of disquiet by, for example, knowing that this was where Hitler stood or by imagining vast fervent National Socialist crowds chanting in unison on the marching fields.

Sharon Macdonald (182) Difficult Heritage

During the Day of the Hitler Youth of September 11, 1937, and standing on the same podium now. By this time the Hitler Youth now had five million members and was the largest youth organisation in the world. Here Hitler

spoke at a celebration organised by the Hitler Youth whilst it was pouring with rain which Hitler was forced to reference in his speech: "This morning I learned from our weather forecasters that, at present, we have the meteorological condition “V b.” That is supposed to be a mixture between very bad and bad. Now, my boys and girls, Germany has had this meteorological condition for fifteen years! And the Party had this meteorological condition, too! For the space of a decade, the sun did not shine upon this Movement. It was a battle in which only hope could be victorious, the hope that in the end the sun would rise over Germany after all. And risen it has! And as you are standing here today, it is also a good thing that the sun is not smiling down on you. For we want to raise a race not only for sunny, but also for stormy days!"

During the Day of the Hitler Youth of September 11, 1937, and standing on the same podium now. By this time the Hitler Youth now had five million members and was the largest youth organisation in the world. Here Hitler

spoke at a celebration organised by the Hitler Youth whilst it was pouring with rain which Hitler was forced to reference in his speech: "This morning I learned from our weather forecasters that, at present, we have the meteorological condition “V b.” That is supposed to be a mixture between very bad and bad. Now, my boys and girls, Germany has had this meteorological condition for fifteen years! And the Party had this meteorological condition, too! For the space of a decade, the sun did not shine upon this Movement. It was a battle in which only hope could be victorious, the hope that in the end the sun would rise over Germany after all. And risen it has! And as you are standing here today, it is also a good thing that the sun is not smiling down on you. For we want to raise a race not only for sunny, but also for stormy days!"  The 335 m² hall was only completed in 1939, and was to be used for the first time during the party rally of that year. Large sculptures created for the four niches in the foyer by Kurt Schmid-Ehmen were never installed. At short notice, the “Party Rally of Peace” was cancelled before Germany attacked Poland and unleashed the war. The Golden Hall is the only remaining interior planned by Speer, remaining an impressive example of Nazi architecture’s resemblance to stage sets. The 36.5 × 8.7 metre-high walls are made of Lahn marble slabs whilst the ceiling which reaches a height of 7.8 metres is decorated with shimmering gold mosaics by Hermann Kaspar. The original purpose and use of the golden hall during the Nazi party rallies is no longer known today. From 1985 to 2001 it housed the Fascination and Violence exhibition, which provided the impetus for the Documentation Centre Nazi Party Rally Grounds. In 1986, the post-industrial band Einsturzende Neubauten performed in the hall for the only concert to date in the premises. Frontman Blixa Geld described the performance as a counter to its totalitarian history. Currently the Golden Hall can only be visited as part of a guided tour of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds although apparently the permanent opening of a section is planned.

The 335 m² hall was only completed in 1939, and was to be used for the first time during the party rally of that year. Large sculptures created for the four niches in the foyer by Kurt Schmid-Ehmen were never installed. At short notice, the “Party Rally of Peace” was cancelled before Germany attacked Poland and unleashed the war. The Golden Hall is the only remaining interior planned by Speer, remaining an impressive example of Nazi architecture’s resemblance to stage sets. The 36.5 × 8.7 metre-high walls are made of Lahn marble slabs whilst the ceiling which reaches a height of 7.8 metres is decorated with shimmering gold mosaics by Hermann Kaspar. The original purpose and use of the golden hall during the Nazi party rallies is no longer known today. From 1985 to 2001 it housed the Fascination and Violence exhibition, which provided the impetus for the Documentation Centre Nazi Party Rally Grounds. In 1986, the post-industrial band Einsturzende Neubauten performed in the hall for the only concert to date in the premises. Frontman Blixa Geld described the performance as a counter to its totalitarian history. Currently the Golden Hall can only be visited as part of a guided tour of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds although apparently the permanent opening of a section is planned. In Germany as this site presents, there are many building relics from

the Nazi era, many of which continue to be used with Nazi paraphernalia

on the façades still intact- the Olympic Stadium in Berlin has remained a sports arena, the former ministries of the German Reich in Berlin were converted into offices, the “House of Art” in Munich

is an exhibition venue. In Nuremberg, the situation is particularly

nuanced however as the Party Rally Grounds and various buildings

designed by Albert Speer served only one main purpose: as a forum for

the glorification of the Nazi regime and Hitler. Germany today has no

need for places for march-pasts and roll calls for 100,000 to 200,000

people in uniforms or for a megalomaniac Congress Hall for 50,000 party

members which is why the Nazi buildings in Nuremberg could not be

suitably used after 1945. Thus the Nuremberg buildings have remained

largely in their original state with no means to strip them of their

original character whilst the Zeppelin Grandstand itself is only rarely used today with the Zeppelin Field in its vast size of very

little practical value today. Parts of the area are used as sports

fields now; up until the mid-1990s, American forces played sports on the

field and the ring road around the Zeppelin Grandstand (Norisring)

annually hosts motor sport events. Between 2005 and

2011 the city invested over one million euros to safeguard access to the

Zeppelin Grandstand with an additional three million euros spent on

infrastructure such as paths and roads in the immediate surroundings.

Nevertheless, in spite of all the repairs the Zeppelin Grandstand is

collapsing. Since 2010, access for visitors to various areas has been

prohibited for safety reasons with the current assumption being that

sooner or later the spectator steps will have to be blocked off.

According to building experts, the site cannot not be preserved without a

general refurbishment with initial estimates putting the costs at

between 60 and 75 million euros.

In Germany as this site presents, there are many building relics from

the Nazi era, many of which continue to be used with Nazi paraphernalia

on the façades still intact- the Olympic Stadium in Berlin has remained a sports arena, the former ministries of the German Reich in Berlin were converted into offices, the “House of Art” in Munich

is an exhibition venue. In Nuremberg, the situation is particularly

nuanced however as the Party Rally Grounds and various buildings

designed by Albert Speer served only one main purpose: as a forum for

the glorification of the Nazi regime and Hitler. Germany today has no

need for places for march-pasts and roll calls for 100,000 to 200,000

people in uniforms or for a megalomaniac Congress Hall for 50,000 party

members which is why the Nazi buildings in Nuremberg could not be

suitably used after 1945. Thus the Nuremberg buildings have remained

largely in their original state with no means to strip them of their

original character whilst the Zeppelin Grandstand itself is only rarely used today with the Zeppelin Field in its vast size of very

little practical value today. Parts of the area are used as sports

fields now; up until the mid-1990s, American forces played sports on the

field and the ring road around the Zeppelin Grandstand (Norisring)

annually hosts motor sport events. Between 2005 and

2011 the city invested over one million euros to safeguard access to the

Zeppelin Grandstand with an additional three million euros spent on

infrastructure such as paths and roads in the immediate surroundings.

Nevertheless, in spite of all the repairs the Zeppelin Grandstand is

collapsing. Since 2010, access for visitors to various areas has been

prohibited for safety reasons with the current assumption being that

sooner or later the spectator steps will have to be blocked off.

According to building experts, the site cannot not be preserved without a

general refurbishment with initial estimates putting the costs at

between 60 and 75 million euros. From right to left: Amann, Himmler, Lutze, Buch, Rosenberg, Schwarz, K. Hierl, Bormann, standing: Frick, unidentified Labour Corps Leader, and Hitler reviewing the Labour Corps at the 9th Nazi Party rally, dubbed the "Reich Party Congress of Labour” (Reichsparteitag der Arbeit), held from September 6–13, 1937. On September 10 in a speech before these political leaders, Hitler explained the reasoning behind his choice of the above title for the congress by claiming that “[n]ow that we have freed Germany within the last four years, we have the right to enjoy the fruits of our labour.” This wording apparently signalled that Hitler had no extraordinary decisions to announce for the future, but would self-complacently contemplate the past. In fact, this Party Congress was remarkable only for its unusual tranquillity, reflecting the mood of the entire year 1937. With the exception of his customary verbal assaults upon world Bolshevism, not even Hitler’s words could disturb the apparent peace but, in all of his speeches, instead relished in eulogies of his successes in the past and his ambitions for the future.

As Germany copes with mass migration and blows to its economy, like the Volkswagen scandal, and to its pride, like the allegations it paid bribes to secure its hosting of the 2006 World Cup, it also continues to deal with vestiges of its problematic past. In few places are those questions more vivid than in Nuremberg. Should public money be spent to preserve these crumbling sites? Is controlled decay an option for anything associated with the Nazis? Or have Hitler and his architect, Albert Speer, locked future generations into a devilish pact that compels Germans not only to teach the history of the Thousand Year Reich the Nazis proclaimed here but also to adapt it for each new era?

The Zeppelin Field was the most important event location for the party rallies. While the Luitpold Arena was firmly established as the site for the cult for the dead of the SA and ϟϟ, numerous events were staged on the Zeppelin Field. During the roll call of the Reich Labour Service, tens of thousands of their men lined up before the Hitler. Large parades and show manoeuvres of the Wehrmacht were held on the Zeppelin Field. Tanks drove up, flak was fired at aeroplanes thundering over the field at low altitude, in 1938 the prototype of a helicopter landed on the Zeppelin Field. On the “Day of Community”, young men demonstrated “virile strength” in manoeuvres with tree trunks, while young women in so-called “girls’ dances” personified the female role of future mothers desired by the Nazis.

The Zeppelin Field was the most important event location for the party rallies. While the Luitpold Arena was firmly established as the site for the cult for the dead of the SA and ϟϟ, numerous events were staged on the Zeppelin Field. During the roll call of the Reich Labour Service, tens of thousands of their men lined up before the Hitler. Large parades and show manoeuvres of the Wehrmacht were held on the Zeppelin Field. Tanks drove up, flak was fired at aeroplanes thundering over the field at low altitude, in 1938 the prototype of a helicopter landed on the Zeppelin Field. On the “Day of Community”, young men demonstrated “virile strength” in manoeuvres with tree trunks, while young women in so-called “girls’ dances” personified the female role of future mothers desired by the Nazis. Göring, Generaloberst Werner v. Fritsch and Generaladmiral Raeder at the Tag der Wehrmacht on September 14, 1936.

Göring, Generaloberst Werner v. Fritsch and Generaladmiral Raeder at the Tag der Wehrmacht on September 14, 1936.

Several times since 1935 Karl Bodenschatz had overheard Göring and Hitler discuss the possibility that the top army generals might be plotting against the regime, and in the autumn of 1937 Göring asked Blomberg outright whether his generals would follow Hitler into a war. It is clear that by December 1937 Göring had begun to indulge in fantasies of taking supreme command of the armed forces himself in place of Blomberg. The only other candidate would be General von Fritsch. At fifty-eight, Fritsch was not much younger than Blomberg, and Göring felt it unlikely that Hitler would feel comfortable with him. Promoted to colonel- general on April 20, 1936, Fritsch came from a puritan Protestant family. His upright bearing suggested he might even be wearing a lace-up corset. With a monocle screwed into his left eye to help his face remain sinister and motionless, he was an old-fashioned bachelor who loved horses and hated Jews with equal passion.Irving (281) Göring

Four days after Nuremberg fell, the US Army blew up the swastika which had been installed at the centre of the Grandstand. The gold-plated and laurel-wreathed swastika which once crowned Albert Speer’s Zeppelin tribune represented the apotheosis and fulfilment of the swastikas which are still present, but sublimated in the decorative scheme of the tribune’s interior. Ornament as the unconscious graphology of the Volkgeist was thus ‘completed’ in the self-conscious presence of the Nazi symbol, and the sign of a (Gothic, mediaeval) past is linked to the rhetoric of a glorious future, thus avoiding the displacement of tradition implied by an Enlightenment concept of progress. The Tribune swastikas expressed in microcosm Hitler’s aim of uniting the medieval Nuremberg with the ‘modern’ National Socialist city, giving equal weight to a glorious past and a glorious future, and thereby defining the present as a moment of transition from one to the other.

Quinn (63) The Swastika: Constructing the Symbol

A visit to the Nuremberg Zeppelin field as it exists today supplies evidence of a healthy disrespect for the few remaining monuments of National Socialist architecture. On Sundays, Turkish Gastarbeiter and their families picnic in the shade of trees flanking Hitler’s ‘Great Road’, the grand thoroughfare which was intended to link the ancient Nuremberg, the ‘City of Imperial Diets’ with his modern ‘City of the Rallies’. Tennis is played against the walls of the Zeppelin tribune, and teenagers tryst on the steps. However, this reclaiming of Nazi architecture for leisure activity is frustrated by the neo-Nazi swastika graffiti which must constantly be removed from the tribune towers and entranceways. This is also the case at the Olympic stadium in Berlin, where the bronze swastikas which have been partially erased from the ceremonial bell reappear in graffiti on the lavatory walls, contesting with the countering phrase ‘Nazi raus’

Quinn (61)The Swastika: Constructing the Symbol

grounds. Julia Lehner, Nuremberg’s chief culture official, says the intention is not to “rebuild, we won’t restore, but we will conserve. We want people to be able to move around freely on the site. It is an important witness to an era—it allows us to see how dictatorial regimes stage-manage themselves. That has educational value today.” Even though the entire site has been under a preservation order since 1973, the grandstand was assessed for damage until 2007, revealing corrosion, broken stairs, dry rot and mildew. As Daniel Ulrich, head of Nuremberg’s construction department, says, “[t]he damp is the biggest problem. The original construction was quick and shoddy. It was little more than a stage-set designed purely for effect. The limestone covering the bricks is not frost-proof and water has seeped in.” This has left the city with various options. One was to reconstruct the buildings but this threatened to be seen as glorifying the Third Reich. Others favoured a “managed decay” which would have involved the city authorities forced to fence off increasingly large parts of the grounds. On the other hand, others feared that the decaying buildings could emit the kind of “ruin romance” the Albert Speer envisioned as mentioned above. Others called for the entire site just to be bulldozed and have the site's history swept under the carpet. In the end, the decision was made to conserve the ruins in their current state and make them fully accessible. The most complex conservation challenge is the damp that has seeped into the stone walls of the ramparts and grandstand, the steps and facades. A ventilation system will be required to remove humidity from the interiors. About a quarter of the stones in the facades and steps are to be replaced by matching concrete blocks. The top layer of the compacted soil stairs of the ramparts will be replaced.In addition, a new “project room” will be installed in the grandstand. The target date for completion is 2025 at the same time Nuremberg is competing to be the European Capital of Culture that year.

grounds. Julia Lehner, Nuremberg’s chief culture official, says the intention is not to “rebuild, we won’t restore, but we will conserve. We want people to be able to move around freely on the site. It is an important witness to an era—it allows us to see how dictatorial regimes stage-manage themselves. That has educational value today.” Even though the entire site has been under a preservation order since 1973, the grandstand was assessed for damage until 2007, revealing corrosion, broken stairs, dry rot and mildew. As Daniel Ulrich, head of Nuremberg’s construction department, says, “[t]he damp is the biggest problem. The original construction was quick and shoddy. It was little more than a stage-set designed purely for effect. The limestone covering the bricks is not frost-proof and water has seeped in.” This has left the city with various options. One was to reconstruct the buildings but this threatened to be seen as glorifying the Third Reich. Others favoured a “managed decay” which would have involved the city authorities forced to fence off increasingly large parts of the grounds. On the other hand, others feared that the decaying buildings could emit the kind of “ruin romance” the Albert Speer envisioned as mentioned above. Others called for the entire site just to be bulldozed and have the site's history swept under the carpet. In the end, the decision was made to conserve the ruins in their current state and make them fully accessible. The most complex conservation challenge is the damp that has seeped into the stone walls of the ramparts and grandstand, the steps and facades. A ventilation system will be required to remove humidity from the interiors. About a quarter of the stones in the facades and steps are to be replaced by matching concrete blocks. The top layer of the compacted soil stairs of the ramparts will be replaced.In addition, a new “project room” will be installed in the grandstand. The target date for completion is 2025 at the same time Nuremberg is competing to be the European Capital of Culture that year.

Stele number 15 provides information about the substation on Regensburger Straße. Popp, who sits on the board of the architects' association BauLust, was "shocked" when he found out that he had just set up his information board next to a future Burger King branch. A hamburger restaurant negates any real historical debate leading him to complain that "[t]he building is simply used as a shell; that upsets me bitterly." To him the willingness of the city administration and the monument protection to agree to a mundane use such as the sale of chips and burgers reflects a disturbing attitude on their part. In this he's joined by architectural professor Josef Reindl who states that on the one hand, "[i]n the documentation centre the city engages with history and a few hundred metres further on, it no longer cares." The head of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds documentary centre, Hans-Christian Täubrich, also criticises the use of the building to serve American fast food by aditting that only financial interests played a role in the sale of the building and nothing else. Nevertheless, the city's monument protection has ensured that the advertising boards are not screwed to the facade and the external impression is not changed leading to Burger King anchoring its logo to the ground as close to the front of the building as possible.

Stele number 15 provides information about the substation on Regensburger Straße. Popp, who sits on the board of the architects' association BauLust, was "shocked" when he found out that he had just set up his information board next to a future Burger King branch. A hamburger restaurant negates any real historical debate leading him to complain that "[t]he building is simply used as a shell; that upsets me bitterly." To him the willingness of the city administration and the monument protection to agree to a mundane use such as the sale of chips and burgers reflects a disturbing attitude on their part. In this he's joined by architectural professor Josef Reindl who states that on the one hand, "[i]n the documentation centre the city engages with history and a few hundred metres further on, it no longer cares." The head of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds documentary centre, Hans-Christian Täubrich, also criticises the use of the building to serve American fast food by aditting that only financial interests played a role in the sale of the building and nothing else. Nevertheless, the city's monument protection has ensured that the advertising boards are not screwed to the facade and the external impression is not changed leading to Burger King anchoring its logo to the ground as close to the front of the building as possible. The Ehrenhalle is located at one end of the Luitpoldhain, a 21-hectare park located in the southeast of Nuremberg northwest of Volkspark Dutzendteich and which extends between Münchner Straße, Bayernstraße and Schultheißallee; on the northern edge is the Meistersingerhalle. In 1927 the first Nazi Party Rally took place here. At the second rally in 1929, the Nazis incorporated the newly completed the Ehrenhalle into their event. After the Nazis took power in 1933 they held a celebration here where Hitler on a wooden-built grandstand. As of 1933, the Luitpoldhain was transformed by a strictly structured display area as part of the plans of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds, most notably by the so-called Luitpold Arena with an area of 84,000 m². Opposite the honour hall was erected a speaker's platform which was connected by a wide granite path. In this ensemble the Reichsparteitage held its rallies of SA and ϟϟ in front of up to 150,000 spectators. Central to the ritual was the blood flag, which had allegedly been carried along by the Nazis in the Hitler Putsch and which served to consecrate new standards of SA and ϟϟ units through contact. The Luitpoldhalle was eventually destroyed by the RAF during one of the first air raids on Nuremberg in the war on the night of August 28-29, 1942.

The Ehrenhalle is located at one end of the Luitpoldhain, a 21-hectare park located in the southeast of Nuremberg northwest of Volkspark Dutzendteich and which extends between Münchner Straße, Bayernstraße and Schultheißallee; on the northern edge is the Meistersingerhalle. In 1927 the first Nazi Party Rally took place here. At the second rally in 1929, the Nazis incorporated the newly completed the Ehrenhalle into their event. After the Nazis took power in 1933 they held a celebration here where Hitler on a wooden-built grandstand. As of 1933, the Luitpoldhain was transformed by a strictly structured display area as part of the plans of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds, most notably by the so-called Luitpold Arena with an area of 84,000 m². Opposite the honour hall was erected a speaker's platform which was connected by a wide granite path. In this ensemble the Reichsparteitage held its rallies of SA and ϟϟ in front of up to 150,000 spectators. Central to the ritual was the blood flag, which had allegedly been carried along by the Nazis in the Hitler Putsch and which served to consecrate new standards of SA and ϟϟ units through contact. The Luitpoldhalle was eventually destroyed by the RAF during one of the first air raids on Nuremberg in the war on the night of August 28-29, 1942.  The Nazis used the site primarily as a commemoration for the fallen soldiers of the Great War and commemoration of the sixteen "Martyrs of the Movement" of the November 9, 1923 Hitlerputsch in Munich. Hitler, accompanied by ϟϟ-leader Heinrich Himmler and SA-leader Viktor Lutze, strode through the arena over the 240 metre-long granite path from the main grandstand to the terrace of the Ehrenhalle and gave the Nazi salute as shown here in 1937 and the site today. The

central “relic” was the blood flag that was supposedly carried by the

putschists during the Hitler coup. During the consecration of the blood

flag , new standards of SA and ϟϟ units were "consecrated" by touching

the blood flag. The ritual was the climax of the celebration.

The Nazis used the site primarily as a commemoration for the fallen soldiers of the Great War and commemoration of the sixteen "Martyrs of the Movement" of the November 9, 1923 Hitlerputsch in Munich. Hitler, accompanied by ϟϟ-leader Heinrich Himmler and SA-leader Viktor Lutze, strode through the arena over the 240 metre-long granite path from the main grandstand to the terrace of the Ehrenhalle and gave the Nazi salute as shown here in 1937 and the site today. The

central “relic” was the blood flag that was supposedly carried by the

putschists during the Hitler coup. During the consecration of the blood

flag , new standards of SA and ϟϟ units were "consecrated" by touching

the blood flag. The ritual was the climax of the celebration.Arguably the most powerful scene in a film that has many is Hitler’s speech at the memorial for the late Paul von Hindenburg, Germany’s most famous World War I commander and Hitler’s predecessor as the Weimar President. The Führer is surrounded by over a quarter of a million civilians and troops from the Nazi special Schutz Staffel (“Shield Squadron,” or ϟϟ , Hitler’s personal bodyguard) and Sturm Abteilung (“Storm Troopers,” or SA, an earlier paramilitary outfit eventually superseded by the ϟϟ). Hitler, flanked by ϟϟ commander Heinrich Himmler and SA commander Viktor Lütze, slowly marches towards Hindenburg’s memorial and gives the Nazi salute in absolute silence.

Stout, Michael J. (23) The Effectiveness of Nazi Propaganda

The film contains

excerpts from speeches given by various Nazi leaders at the Congress,

including those by Hitler, interspersed with footage of massed party

members. Hitler commissioned the film whilst serving as unofficial

executive producer; his name appears in the opening titles. The

overriding theme is the return of Germany as a great power, with Hitler

as the True German Leader who will bring glory to the nation. Much of it

takes place in the Zeppelin field- the second day shows an outdoor

rally for the Reichsarbeitsdienst

(Labour Service), which is primarily a series of pseudo-military drills

by men carrying shovels. The following day starts with a Hitler Youth

rally on the parade ground again showing Nazi dignitaries arriving with

Baldur von Schirach introducing Hitler. There then follows a military

review featuring Wehrmacht cavalry and various armoured vehicles.

The film contains

excerpts from speeches given by various Nazi leaders at the Congress,

including those by Hitler, interspersed with footage of massed party

members. Hitler commissioned the film whilst serving as unofficial

executive producer; his name appears in the opening titles. The

overriding theme is the return of Germany as a great power, with Hitler

as the True German Leader who will bring glory to the nation. Much of it

takes place in the Zeppelin field- the second day shows an outdoor

rally for the Reichsarbeitsdienst

(Labour Service), which is primarily a series of pseudo-military drills

by men carrying shovels. The following day starts with a Hitler Youth

rally on the parade ground again showing Nazi dignitaries arriving with

Baldur von Schirach introducing Hitler. There then follows a military

review featuring Wehrmacht cavalry and various armoured vehicles. Hitler then reviews the parading SA and ϟϟ men,

following which Hitler and Lutze deliver a speech where they discuss

the Night of the Long Knives purge (aka Operation Hummingbird) of the SA several months prior. The latter was the newly appointed leader of the brown-shirts, having just replaced the murdered Ernst Röhm after Operation Hummingbird. During his first official appearance as Stabschef, Shirer notes that “the SA boys received him coolly”. In one of the final scenes, Hitler holds a speech with references towards “unity” and “loyalty”, alluding to the reason for the Night of the Long Knives. This post-Operation Hummingbird aura is explicit in Triumph of the Will, and is especially heavy in the scene depicting Hitler’s address to the Schutzstaffel and the Sturmabteilung. Despite their positions and formations having aesthetic purposes, it is still evident that there was a rift between the two groups, the former being closer to Hitler than the latter, resulting in drunk quarrels during the Rally. These were, needless to say, excluded from the film. Nevertheless, the cold animosity and tension is evident. Kershaw argues that, although following the Night of the Long Knives the Sturmabteilung was forfeited its importance, Hitler could now have confidence in the freshly cleansed bloc. Triumph of the Will suggests otherwise as during Hitler’s speech, the ϟϟ surround him in a protective stance, suggesting the brown-shirts’ adherence was still doubted. Shirer confirms this in his “Berlin Diary” stating that “there was considerable tension in the stadium and I noticed that Hitler’s own ϟϟ bodyguard was drawn up in force in front of him, separating him from the mass of the brown-shirts. We wondered if just one of those fifty thousand brown-shirts wouldn’t pull a revolver, but not one did”. Martin Davidson, in his account of his grandfather’s life as an ϟϟ man, asserts that Hitler was vulnerable at a time so soon after the Night of the Long Knives and there existed considerable animosity between the two groups, culminating in fights and brawls under the influence of alcohol behind the scenes of the 1934 Rally.

Hitler then reviews the parading SA and ϟϟ men,

following which Hitler and Lutze deliver a speech where they discuss

the Night of the Long Knives purge (aka Operation Hummingbird) of the SA several months prior. The latter was the newly appointed leader of the brown-shirts, having just replaced the murdered Ernst Röhm after Operation Hummingbird. During his first official appearance as Stabschef, Shirer notes that “the SA boys received him coolly”. In one of the final scenes, Hitler holds a speech with references towards “unity” and “loyalty”, alluding to the reason for the Night of the Long Knives. This post-Operation Hummingbird aura is explicit in Triumph of the Will, and is especially heavy in the scene depicting Hitler’s address to the Schutzstaffel and the Sturmabteilung. Despite their positions and formations having aesthetic purposes, it is still evident that there was a rift between the two groups, the former being closer to Hitler than the latter, resulting in drunk quarrels during the Rally. These were, needless to say, excluded from the film. Nevertheless, the cold animosity and tension is evident. Kershaw argues that, although following the Night of the Long Knives the Sturmabteilung was forfeited its importance, Hitler could now have confidence in the freshly cleansed bloc. Triumph of the Will suggests otherwise as during Hitler’s speech, the ϟϟ surround him in a protective stance, suggesting the brown-shirts’ adherence was still doubted. Shirer confirms this in his “Berlin Diary” stating that “there was considerable tension in the stadium and I noticed that Hitler’s own ϟϟ bodyguard was drawn up in force in front of him, separating him from the mass of the brown-shirts. We wondered if just one of those fifty thousand brown-shirts wouldn’t pull a revolver, but not one did”. Martin Davidson, in his account of his grandfather’s life as an ϟϟ man, asserts that Hitler was vulnerable at a time so soon after the Night of the Long Knives and there existed considerable animosity between the two groups, culminating in fights and brawls under the influence of alcohol behind the scenes of the 1934 Rally. In some cases, such as the visual allusions to Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will that cap the concluding medal ceremony of A New Hope, the reference could only become clear in the context of the saga as a whole. In that case, the allusion to the Rebel victory as a quasi-fascist one suggested the moral hollowness of their victory achieved by military force, while setting the stage for their defeat at the start of the second film. The only enduring victories in these films are those built on love, understanding, and mutual self-sacrifice.

Such comparisons can be made alongside Ridley Scott's Gladiator with its depiction of Commodus's entry into Rome (although Scott has pointed out that the iconography of Nazi rallies was of course inspired by the Roman Empire). Gladiator reflects back on the film by duplicating similar events that occurred in Hitler's procession. The Nazi film opens with an aerial view of Hitler arriving in a plane, whilst Scott shows an aerial view of Rome, also seen through clouds, quickly followed by a shot of the large crowd of people watching Commodus pass them in a procession with his chariot. The first thing to appear in Triumph of the Will is a Nazi eagle, which is alluded to when a statue of an eagle sits atop one of the arches (and then shortly followed by several more decorative eagles throughout the rest of the scene) leading up to the procession of Commodus. At one point in the Nazi film, a little girl gives flowers to Hitler, whilst Commodus is met with several girls that all give him bundles of flowers.

Such comparisons can be made alongside Ridley Scott's Gladiator with its depiction of Commodus's entry into Rome (although Scott has pointed out that the iconography of Nazi rallies was of course inspired by the Roman Empire). Gladiator reflects back on the film by duplicating similar events that occurred in Hitler's procession. The Nazi film opens with an aerial view of Hitler arriving in a plane, whilst Scott shows an aerial view of Rome, also seen through clouds, quickly followed by a shot of the large crowd of people watching Commodus pass them in a procession with his chariot. The first thing to appear in Triumph of the Will is a Nazi eagle, which is alluded to when a statue of an eagle sits atop one of the arches (and then shortly followed by several more decorative eagles throughout the rest of the scene) leading up to the procession of Commodus. At one point in the Nazi film, a little girl gives flowers to Hitler, whilst Commodus is met with several girls that all give him bundles of flowers. The parallels between Commodus’ parade of power in Rome and Hitler’s arrival at a Nazi rally in Nuremberg are unmistakable. Both scenes open with aerial views of monumental buildings and cheering crowds, both offer shots from the viewpoint of the central figure, the camera angles making Commodus and Hitler seem larger than life. In an explicit quotation of the moment in Hitler’s progress when he is offered flowers by a little girl, Commodus on the steps of the Senate House is presented with bouquets by children. In Ridley Scott’s Rome, the Senate House faces the Colosseum across a vast square filled with the massed ranks of soldiers. This grandiose vision of the architecture of domination owes most to Hitler’s plans for a new Berlin. Rome in the 2nd century AD, with its narrow streets and densely built Forum, was never like this. It only came close in 1932 when Mussolini drove his processional Via dell’Impero straight through the centre of the city.

I’m beginning to comprehend, I think, some of the reasons for Hitler’s astounding success. Borrowing a chapter from the Roman church, he is restoring pageantry and colour and mysticism to the drab lives of twentieth-century Germans. This morning’s opening meeting in the Luitpold Hall on the outskirts of Nuremberg was more than a gorgeous show; it also had something of the mysticism and religious fervour of an Easter or Christmas Mass in a great Gothic cathedral. The hall was a sea of brightly coloured flags. Even Hitler’s arrival was made dramatic. The band stopped playing. There was a hush over the thirty thousand people packed in the hall. Then the band struck up the Badenweiler March, a very catchy tune, and used only, I’m told, when Hitler makes his big entries.

The Luitpoldhalle: Dating back to the Bavarian Exposition, the former machine hall was renovated and first used by the Nazis for the party convention party congress of 1934. Its monumental neo-classic façade featured a shell limestone facing with three enormous entrance portals. It was in this building during the party congress of 1935, that the Nuremberg laws were adapted which deprived German Jews and other minorities of their citizenship. The

Luitpoldhalle had an extension of 180 x 50 metres and offered space for

up to 16,000 people. Within it the party congress took place during the

Reichsparteitages. From 1933 to 1936 the largest organ in Europe with five manuals and 220 registers was installed within the hall. The

structure was severely damaged by allied bombs in early 1945 and a

few years later replaced by a parking lot. Part of the granite staircase

leading to the building remains intact today as seen in this GIF.

The Luitpoldhalle: Dating back to the Bavarian Exposition, the former machine hall was renovated and first used by the Nazis for the party convention party congress of 1934. Its monumental neo-classic façade featured a shell limestone facing with three enormous entrance portals. It was in this building during the party congress of 1935, that the Nuremberg laws were adapted which deprived German Jews and other minorities of their citizenship. The

Luitpoldhalle had an extension of 180 x 50 metres and offered space for

up to 16,000 people. Within it the party congress took place during the

Reichsparteitages. From 1933 to 1936 the largest organ in Europe with five manuals and 220 registers was installed within the hall. The

structure was severely damaged by allied bombs in early 1945 and a

few years later replaced by a parking lot. Part of the granite staircase

leading to the building remains intact today as seen in this GIF.  This facility was completely reworked for the rallies. The former landscaped pleasure park was callously levelled, flanked by massive stone grandstands and transformed into the Luitpold Arena. The resulting formalised space served as the stage for one of the most moving moments of the rally schedule. On the seventh day of the proceedings, the massed ranks of more than 150,000 SA and ϟϟ Storm Troopers filled the floor of the arena. Hitler and his entourage then passed solemnly between the ranks along a granite path leading straight to the steps of the war memorial, where the Führer would pay his respects to the nation's and the party's martyred dead. Connected to the Luitpold Arena was the Luitpold Hall, a meeting hall with a capacity for sixteen thousand people redesigned and enlarged from a structure built for the 1906 Bavarian Jubilee Exhibition.

This facility was completely reworked for the rallies. The former landscaped pleasure park was callously levelled, flanked by massive stone grandstands and transformed into the Luitpold Arena. The resulting formalised space served as the stage for one of the most moving moments of the rally schedule. On the seventh day of the proceedings, the massed ranks of more than 150,000 SA and ϟϟ Storm Troopers filled the floor of the arena. Hitler and his entourage then passed solemnly between the ranks along a granite path leading straight to the steps of the war memorial, where the Führer would pay his respects to the nation's and the party's martyred dead. Connected to the Luitpold Arena was the Luitpold Hall, a meeting hall with a capacity for sixteen thousand people redesigned and enlarged from a structure built for the 1906 Bavarian Jubilee Exhibition. The Fliegerdenkmal, a monument to the pilots killed in the Great War designed in 1924 by Walter Franke for the fallen German pilots of the First World War which is today located directly behind the Ehrenhalle, and as it appeared in a Nazi-era postcard. It presents a crashed, upside-down plane made of limestone topped with a bronze eagle. It was originally located on Dutzendteichstraße, but was relocated to Marienbergstraße on the occasion of the opening of the new Nuremberg airport on Marienberg. During the Second World War it had ended up being severely damaged and was eventually restored in 1958, now commemorating the fallen pilots of both world wars.

'the harsh law of architecture', which has always and in all its parts been a masculine affair, can be summarised into a clear concept: It must be strict, of a concise, clear, even classical form. It has to be easy. It must carry within itself the standard of the 'reaching to heaven'. It must go beyond the usual measure borrowed from the benefit. It must be made of the solid, firmly fixed and built according to the best rules of the craft as for eternity. It must be pointless in the practical sense, but it must be the bearer of an idea. It must carry something unapproachable that fills people with admiration, but also with shyness. It must be impersonal because it is not the work of an individual, but a symbol of a community connected by a common ideal.

Taking my students from the Bavarian International School on tour

Speer apparently chose a horseshoe shape for his building after rejecting the oval shape of an amphitheatre. The last-mentioned plan would have intensified the heat after Speer's assertion, as well as a psychological disadvantage - a comment which he did not elaborate. When Speer mentioned the enormous cost of the building, Hitler, who laid the foundation on September 9, 1937, replied that the construction would cost less than two battleships of the Bismarck class. Wolfgang Lotz, who wrote about the German Stadium in 1937, commented that it would take twice the number of spectators who would have found a place in the Circus Maximus in Rome. Inevitably at that time, he also highlighted the community feeling that would create such a building between competitors and spectators:

As in ancient Greece, the elite and highly experienced men are chosen from among the masses of the nation. An entire nation in sympathetic astonishment sits in the ranks. Spectators and contestants go into one unit.The idea of organising Paneuropean track and field athletics contests was perhaps inspired by the Panathenes, but Speer's stadium was stylistically more committed to ancient Rome than the Greeks; with its huge vaulted base and the arched exterior façade, it was more like the Circus Maximus than the style of the Athens Panathinaiko Stadium. Again a Nazi building represented a mixture of Greek and Roman elements, mostly involving the latter. But Hitler did not want such a stadium to be the centre of German athletics. The restored Panathinaiko Stadium in Athens had been used for the Olympic Games in 1896 and 1906. In 1936 the games were held on the Reichsportfeld in Berlin, but Hitler insisted that all future games in the German stadium should take place after 1940, when the games were planned in Tokyo. This stadium was much larger than Berlin's Olympiastadion, which had a capacity of 115,000 spectators. Hitler's assumed that after victory in the war the subjugated world would have had no choice but to send all athletes to Germany every four years for the Olympic Games. Pangermanic games should be of equal importance with a worldwide competition, in which the winners would have received their reward from the Führer, surrounded by loyalists of the party, who were to be placed in the straight transverse axis of the stadium, referring to ancient gods.

Hitler, as late as July 6, 1942, enthused about the prospects of the Reichsparteitagsgelände and proposed Deutsches Stadion:

Hitler, as late as July 6, 1942, enthused about the prospects of the Reichsparteitagsgelände and proposed Deutsches Stadion:The Party Rally has, however, been not only a quite unique occasion in the life of the NSDAP but also in many respects a valuable preparation for war. Each Rally requires the organisation of no fewer than four thousand special trains. As these trains stretched as far as Munich and Halle, the railway authorities were given first-class practice in the military problem of handling mass troop transportation. Nor will the Rally lose its significance in the future. Indeed, I have given orders that the venue of the Rally is to be enlarged to accommodate a minimum of two million for the future—as compared to the million to a million and a half to-day. The German Stadium which has been constructed at Nuremberg, and of which Horth has drawn two magnificent pictures, accommodates four hundred thousand people and is on a scale which has no comparison anywhere on earth.

With the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the situation of PoWs in German detention changed dramatically. Millions of Red Army soldiers were captured, and many of these, along with other PoWs, were used as forced labor in the German war economy. The camp's role evolved further when it began functioning as a Dulag (Durchgangslager or transit camp) due to Nuremberg's significance as a railroad hub. Stalag XIII D was officially reestablished in April 1943 and, along with the Oflags (camps for officers) that were also on the site, suffered heavy damage during an Allied air raid in August 1943. Despite the destruction of two-thirds of the wooden barracks, only two Soviet soldiers were reported as casualties in this attack. However, many PoWs fell victim to aerial warfare against Nuremberg during their work assignments or other duties in the city area. As the war neared its end and the Allied forces closed in on Germany from the east and west in late 1944, Stalag XIII D and Oflag 73 became destinations for increasingly chaotic evacuation transports from other German PoW camps. This included the transfer of inmates and staff from the Luftwaffenlager III Sagan in Silesia, which housed approximately 6,000 US and British crew members. The camp's population included a diverse range of nationalities, totaling 29,550 PoWs, including 8,680 officers. The liberation of the Nuremberg camps began with evacuation marches on April 12, 1945, leading to Stalag Moosburg in Upper Bavaria. The Americans freed the Nuremberg camps on April 16, 1945, finding approximately 13,000 quarantined PoWs for typhoid fever, along with Serbian officers and the staff of the PoW hospital, most of whom were also Serbs. The bulk of the former inmates were liberated on April 29 northwest of Moosburg.

Standing in front of the former ϟϟ-Barracks, built by architect Franz Ruff between 1937 and 1939 on the western outskirts of the Party Rally Grounds. Although referred to by the Nazis as the "Gateway to the Rally Grounds," it was not actually used until after the start of the war- never during the years of the rallies. Its construction demonstrates how the ϟϟ sought to be represented in Nuremberg by its own units right next to the rally grounds. In 1936 no barracks were planned for the Nazi rallies but the ϟϟ, having set up the guard service for the grounds, desired one and in so doing expand its responsibilities and to set up its own troops. Thus in March 1936 ϟϟ-Gruppenführer Ernst-Heinrich Schmauser began planning its construction with an area on Frankenstraße chosen the next year. By July Reichsführer ϟϟ Himmler commissioned Speer to submit blueprints in three months. After an inspection of the site by Himmler and Speer and Willy Liebel, the mayor of Nuremberg, the final plan was decided and Ruff was commissioned as architect whilst remaining responsible for the neighbouring Reichsparteitagsland. Hitler himself interfered in its planning, ordering in September 1937 for an immediate start with accommodation ready by 1938, although the work was not started until October 20. The topping-out ceremony of the main building was celebrated on June 2, 1939 and by 1940 the building complex was largely completed. Officially described as ϟϟ accommodation and never barracks, the main building alone had a thousand rooms. Above the main entrance hung a large reichsadler and the ceilings were covered with mosaics designed by Max Körner whilst the floor of the festival hall consisted of marble mosaics in the form of hooked crossbars. This was one of the Nazis' largest barracks buildings erected and the entire complex consisted of the central main building with a “Portal of Honour”, and two side wings, both built around a courtyard, as well as several additional buildings.

Standing in front of the former ϟϟ-Barracks, built by architect Franz Ruff between 1937 and 1939 on the western outskirts of the Party Rally Grounds. Although referred to by the Nazis as the "Gateway to the Rally Grounds," it was not actually used until after the start of the war- never during the years of the rallies. Its construction demonstrates how the ϟϟ sought to be represented in Nuremberg by its own units right next to the rally grounds. In 1936 no barracks were planned for the Nazi rallies but the ϟϟ, having set up the guard service for the grounds, desired one and in so doing expand its responsibilities and to set up its own troops. Thus in March 1936 ϟϟ-Gruppenführer Ernst-Heinrich Schmauser began planning its construction with an area on Frankenstraße chosen the next year. By July Reichsführer ϟϟ Himmler commissioned Speer to submit blueprints in three months. After an inspection of the site by Himmler and Speer and Willy Liebel, the mayor of Nuremberg, the final plan was decided and Ruff was commissioned as architect whilst remaining responsible for the neighbouring Reichsparteitagsland. Hitler himself interfered in its planning, ordering in September 1937 for an immediate start with accommodation ready by 1938, although the work was not started until October 20. The topping-out ceremony of the main building was celebrated on June 2, 1939 and by 1940 the building complex was largely completed. Officially described as ϟϟ accommodation and never barracks, the main building alone had a thousand rooms. Above the main entrance hung a large reichsadler and the ceilings were covered with mosaics designed by Max Körner whilst the floor of the festival hall consisted of marble mosaics in the form of hooked crossbars. This was one of the Nazis' largest barracks buildings erected and the entire complex consisted of the central main building with a “Portal of Honour”, and two side wings, both built around a courtyard, as well as several additional buildings.

During the war radio operators for the Waffen ϟϟ were trained here, some of whom took part in the siege of Leningrad. During the war radio operators were trained for different units. In addition, the c Barracks Nachrichten-Ersatzabteilung (Nuremberg) had its seat here. In May 1940, prisoners from the Dachau concentration camp came to the barracks for construction and other work. Through 1944-45, a small section of the building was used to provide accommodation for roughly an hundred prisoners from the Dachau and Flossenbürg concentration camps. When Nuremberg was conquered by the Americans in April 1945, German troops from the ϟϟ barracks attempted a final resistance although, apart from bullet holes at the main building, the barracks were scarcely damaged during the war. In April the building complex was renamed Merrell Barracks after a fallen soldier of the 3rd American infantry division and the empty buildings held foreign forced labourers. Today it houses the Federal Department for the Recognition of Foreign [sic] Refugees.